[1]

[1]Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil's president-elect, and Rodrigo Duterte, Philippines’ president elected in 2016. Source of both photos: Wikimedia Commons [2].

There are two main classes of people who call Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil's proudly homophobic, misogynistic, torture-loving president-elect, the “Trump of the tropics”: North American journalists and, well, Bolsonaro himself, who painstakingly models his image on that of his USA muse.

It's partly true that the Brazil election story, in the end, is just the latest installment in the zeitgeist of political breakdown sweeping the democratic world, of which Donald Trump is the most famous example. Simmering public discontent with the practices of political elites, or — depending on your preferred flavour of analysis — hatred that should have no place in society to begin with finds fertile ground on social media designed to ensnare primary impulses in a ceaseless cycle of reward, reinforce, repeat. The discontent turns into paranoia, latching on to conspiracy theories in which a — usually disenfranchised — section of the populace is demonized, and the whole thing eventually finds its embodiment in a wannabe statesman, a messiah with a penchant for hyperbole who promises a complete overhaul of the political establishment. Et voilà.

It's not that the Bolsonaro-Trump analogy is a bad one. But there’s another incarnation of the pattern described above that is even more like Bolsonaro: the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte. It makes sense that Brazilians [3] and Filipinos [4] are gazing at each other as they try to understand their own versions of the same story, if only because of their leaders’ vows to exterminate massive numbers of people in their respective homelands.

At some point in his 2016 campaign, Duterte declared that if he was elected, so many bodies would be dumped into Manila Bay that the “fish would grow fat” from feeding on them. Bolsonaro expressed similar sentiments on the campaign trail two years later, saying he'd give police officers ‘carte blanche’ to kill on duty. Duterte has admitted to having personally killed suspects during his time as mayor of the city of Davao, and he's very likely the brains behind the infamous Davao Death Squad. Bolsonaro is a former army captain who openly says he's “in favour of torture.” Duterte's promises turned out not to be so empty: 20,000 civilians have allegedly been killed in his so-called ‘war on drugs’ in the past two years. The International Criminal Court opened an investigation against him for crimes against humanity, and he has ordered the withdrawal of the Philippines from the Court [5].

Also unlike Trump, it wasn't primarily poor, rural Brazilians and Filipinos who elected Bolsonaro and Duterte. Both men also wooed the urban middle classes — small business owners, liberal professionals, members of the police and the armed forces — who are fearful of rampant crime. That's the same middle class who once enthusiastically supported dictatorships in each country, then helped end them.

Although both Bolsonaro and Duterte have come to embody fear and public discontent and pose as outsiders and spokesmen of the people, they are both career politicians who leapfrogged from the fringes of the political class in their respective republics to the presidency. Bolsonaro is a four-term congressman who changed parties eight times and successfully led a striking total of two bills. Duterte as a three-decade mayor of a southern city that he now claims was sidelined by Manila, ignoring the fact that he supported the previous Liberal Party government up until his last minute as mayor, and only turned against them when he decided to run for president.

Not so fast

These resemblances haven't been lost on either the Brazilian or Philippine media, but the truth is that apart from the war on drugs, the two politicians ran their campaigns on quite different platforms.

Take Bolsonaro's economic policy: his University of Chicago-educated economic minister has promised [6] a host of ultra-orthodox reforms, including privatization of Brazil's state companies and reform of the pensions system. He also embraces Michel Temer's ‘unrestricted outsourcing’ law, which was approved by Congress in 2017 and allows companies’ core jobs to be outsourced and denies benefits to workers.

Outsourcing is a big issue too in the Philippines’ political debate, where it's commonly called contractualization. Contrary to Bolsonaro, Duterte campaigned on a promise to end contractualization, signing [7] an order in 2018 in support of this pledge. Labour groups, however, have considered it as an empty gesture, as it hasn’t outlawed the practice.

Duterte has also sponsored a tax reform package [8], approved by Congress in 2017, that created new tiers for the super-rich while raising taxes on consumer goods and services such as fuel, sugary drinks, cars, tobacco, and cosmetic surgery. Under his flagship program “Build, Build, Build”, he has poured money — clinched through loans from China — into infrastructure. Dutertenomics bear a closer resemblance to the policies of Brazil's former president Dilma Rousseff, which contributed to a large budget deficit and the mounting inflation that has fueled Brazil's current predicament.

And while Bolsonaro promises to begin imposing tuition fees in Brazil's public universities — which have always been completely free — Duterte signed [9] the Free Tertiary Education law, which provides qualified students tuition-free access to public higher education. It's unclear whether this is even feasible, given the country's funding constraints, but even Duterte critics acknowledge the potential benefits of this law.

Since being elected, Bolsonaro appears to have rolled back [10] his pledge to withdraw Brazil from the Paris agreement and close the Ministry of Environment, but not his promises to obliterate all of Brazil's pro-indigenous and pro-conservation legislation, including putting a stop to indigenous land allocations and opening indigenous territories to large-scale mining.

Duterte, on the other hand, has stood consistently against open-pit and large-scale mining. He appointed a well-known environmental activist to head the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), and didn’t oppose the DENR’s suspension of several mining firms and calls for a mining audit. Even with a new DENR secretary in the position, Duterte continues to criticize [11] mining firms while maintaining a ban [12] against new open-pit mining operation.

It's (not just) the economy, stupid

Bolsonaro and Duterte also came to power in the context of two different realities.

Brazil is still reeling from an economic recession — 2016 saw the worst downturn since the 1980s. A large-scale corruption probe put dozens of businessmen and politicians in jail, including former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Dilma Rousseff, who succeeded Lula in 2011, was impeached in 2016 for window-dressing government accounts. Both events deeply divided Brazilians, who have tended to see them either as flagrant assaults on the constitution by a small faction of the judiciary and a corrupt Congress, or as the long-yearned-for salvation the country needed, and its judges and prosecutors as nothing less than heroes. It was on that wave of chaos that Bolsonaro surfed to victory.

With Duterte, on the other hand, nobody saw it coming. His predecessor, the Liberal Party's Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino, left office with a 50 per cent approval rating — nearly as high as when he took power six years earlier, a feat to which few politicians can lay claim. In 2015, too, the Philippines’ economy experienced growth of over six per cent.

Duterte ran for president posing as a “Leftist”, while Bolsonaro leveraged the deep-rooted, multi-generation fear of communism. Such fears have underpinned Latin America right-wing politics for nearly a century, with the Workers’ Party being the latest incarnation of this evil force.

Like much of Latin America and Southeast Asia, both Brazil and the Philippines experienced communist insurgencies in the mid-20th century. But while Brazil's dictatorship wiped out its rebels, with many of them being absorbed by democratization, the armed insurgency in the Philippines lives on. Since the restoration of democracy in the 1980s, no Philippine president has succeeded in signing a peace deal with the New People's Army (NPA), the armed wing of the Communist Party, whose cadres, according to the military, number only [13] around 3,000 (down from 20,000 at its peak in the late 1970s).

Duterte had an amicable relationship with the NPA during his time as mayor of Davao, the largest city in Mindanao, the island where most of the NPA forces are concentrated. As president, he resumed peace talks with the communists, released some political prisoners, and advanced negotiations on the distribution of free [14] land and irrigation services for small farmers.

But last year Duterte removed the Leftists from his Cabinet and the peace negotiations with the communists have stalled [15]. Like his predecessors, Duterte is now waging an all-out war against the NPA.

From dictatorship to (cacique) democracy

Both Brazil and the Philippines and their current political establishments emerged in the mid-1980s following violent US-backed dictatorships. Brazil's military regime, which ruled from 1964 through 1985, and Ferdinand Marcos, who ruled from 1965 to 1986, both leveraged pledges to root out communist insurgents to give themselves legitimacy.

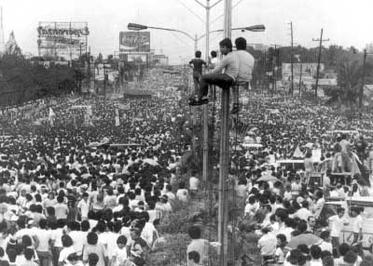

[16]

[16]People Power Revolution: people filling up Epifanio delos Santos Avenue (EDSA), Metro Manila, Philippines. February 7, 1986. Photo: Joey de Vera, published by Wikimedia Commons under fair use.

Suspension of free elections, suppression of press freedom, violent targeting of dissidents and widespread use of torture and disappearances were hallmarks of both regimes. In neither country have the crimes of those periods been brought to justice.

The two republics experienced a return to democracy around the same time — Brazil in 1983-84 with Diretas Já, and the Philippines’ People Power Revolution in 1986 — both brewed amid raging economic recession. The Philippines’ movement ousted Marcos after he rigged the 1986 elections, installing Corazón Aquino as president, who along with an appointed commission drafted a 1987 constitution. Following Diretas, Brazilians elected a Constituent Assembly in 1986 which drafted the country's 1988 constitution.

[17]

[17]Diretas Já Demonstration in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil, on April 13, 1984. Photo: Alfonso Abraham/Senado Federal CC-BY-NC 2.0

Among the many legacies of both movements is the creation of the political elites who would rule their countries for the next three decades. But while Brazil's Diretas united the liberals and the more radical leftist opposition, the Philippines’ Communist Party boycotted the 1986 elections in what they later admitted was a serious tactical mistake. Despite having been the core of the resistance to Marcos throughout the 1970s, the Communist Party remained underground as the Philippines transitioned to democracy. Meanwhile, Brazil’s transition took place with a robust leftist force at the helm — the Workers’ Party (PT), whose leader Lula rose through the ranks of Brazil's unions to preside over an unprecedented economic boom between 2002-2010.

While the PT's politics transformed the lives of the poorest Brazilians, they largely failed to produce lasting structural change, and over time they began to look the same as their liberal predecessors. If, on one hand, the PT respected Brazil's democratic institutions, it also played the game of politics, which in Brazil is rigged by a greedy oligarchy and corrupt patron-client electoral practices — just like the Philippines.

Fearing for democracy

It's no coincidence that both Bolsonaro and Duterte speak nostalgically of their country's bygone repressive regimes as allegedly free of violence, corruption, and chaos, and have cosied up to its leaders. The emergence of these two political figures has come on the heels of the failure of young liberal democracies. Both countries have failed to address structural injustice and high levels of inequality and corruption at all levels of a body politic commandeered by a handful of caciques.

It is no wonder, then, that both the Philippines and Brazil fell for two strongmen who wooed them with hyperbolic promises of rooting out all crime and corruption, even if at the expense of the democratic edifice built over the past three decades.

In two and half years as president, Duterte has removed the chief justice of the Supreme Court and charged and imprisoned his most vocal opponent in the Senate on counts of drug trafficking in a scandalous trial. He tried to revoke the license of Rappler, a major online news outlet in the Philippines, and banned their main reporter from Malacañang Palace, while legions of DDS (Die-Hard Duterte Supporters) threaten many more journalists [18] online.

Whether Bolsonaro will also dismantle democracy in Brazil remains to be seen. Many hope that on facing the actual responsibilities of power he will moderate his tone and his policies. But if Duterte — in many respects the less reactionary figure — is any example, Brazilians have reason enough to be afraid.