For many within Venezuela and abroad, Big Brother is tightening his grip on the nation. References online comparing George Orwell's popular novel with the situation in Venezuela have not been few, isolated or only recently mentioned.

Winston Smith, the novel's main character, wants to rebel and collaborate with the overthrowing of the government that controls its citizens and brutally punishes those who commit crimes — or even think about doing so.

Orwell's novel succeeds in portraying a totalitarian government that controls and manages the public and private lives of its citizens. And beyond the book and its story, Orwell also creates a universe of symbols and metaphors in which language and history are important pieces of a solid strategy for social control.

Orwell's totalitarian portrayal has also reached a universality that few novels have achieved. Venezuelans haven't been the first [2] to compare 1984 to the regimes that have ruled their countries.

However, the profound crises [3] that Venezuela actually faces in many areas, not to mention the economic and social [4] collapse, have permeated the daily life of its citizens. Many compare [5] characteristics of Orwell's Oceania to the political system established by Hugo Chávez and continued by his successor, Nicolás Maduro.

A “Bolivarian Ingsoc”

[6]

[6]Caracas, March 5, 2014. Commemoration of the death of President Hugo Chávez Frías. Photo: Xavier Granja Cedeño. Shared under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

For many netizens, there are numerous examples of 1984 in today’s Venezuela. For example, in 2017,1984 was staged in a theatrical adaptation [7]. On Twitter, tags for Venezuela and 1984 [8] appear regularly, and there has been comparisons between Ingsoc, the fictional political party of the novel [9], and the United Socialist Party of Venezuela [10]:

Escuchaba en audiolibro unos fragmentos de 1984, la novela de Orwell, era como escuchar una descripción de la Venezuela actual. Carteles con ojos que te siguen, apagones, celebraciones patrias, propaganda política sobre los grandes logros del régimen.

— J.C Méndez Guédez (@mendezguedez) June 5, 2018 [11]

I listened to some sections of the audio book of 1984, Orwell's novel. It was like listening to a description of Venezuela today. Posters with eyes that follow you, blackouts, patriotic celebrations, political propaganda about the regime's great achievements.

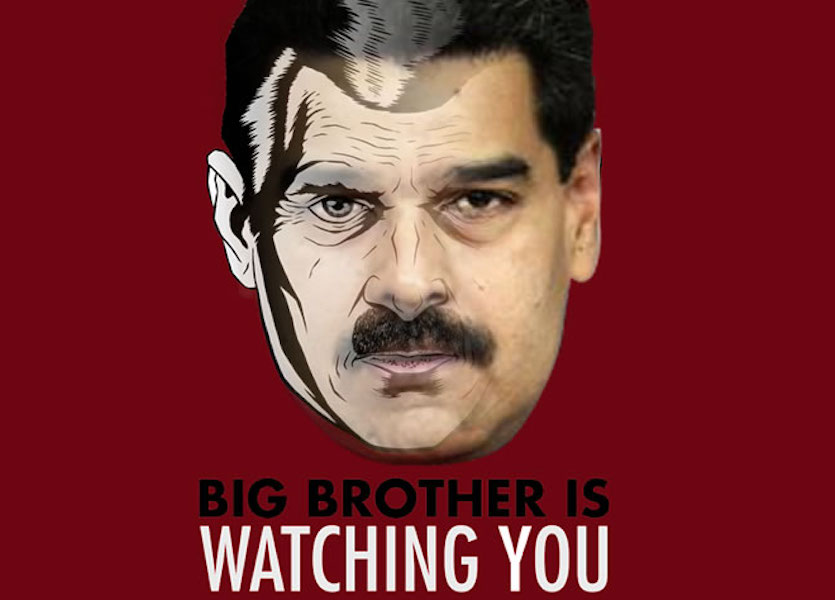

#GegeTuit [12] Recordando la Novela 1984 de #Orwell [13], mezclada con Rebelión en la Granja, creo el escritor jamás imaginó que #Venezuela [14] sería la mejor puesta en escena de sus obras, el que las ha leído me entenderá!

El Cerdo Mayor con Bigotes, que comanda el Ingsoc Bolivariano! pic.twitter.com/X6znY35jKL [15]— GéGé (@GegeRpz) May 17, 2018 [16]

#GegeTuit [12] Remembering #Orwell's novel 1984 of together with Animal Farm. I think the author never imagined that #Venezuela [14] would be the best stage for his novels. The one who's read these novels will understand!

The Main Mustached Pig commands the Bolivarian Ingsoc! pic.twitter.com/X6znY35jKL [15]

Now, not only those opposed to the government see reflections of Oceania in Venezuela. Food [17] and medicine [18] shortages, as well as the series of protests [19] that have turned violent have evoked similar opinions from some who support Nicolás Maduro's government. From their perspective, however, the repression comes from foreign influence and governmental opposition. Guillermo Moreno expresses it this way on the online collective (generally in support of the government) Aporrea [20]:

…recordé las largas colas para un pote de leche, para un pañal, para una medicina Y no pude dejar de asociar ese sufrimiento y esa tortura como una forma mas de manipulación que ejerce un estado para lograr sus objetivos […] Y es que el antiguo estado capitalista en Venezuela aun mantiene intacto todo su poder. Ese que tiene para dejarnos sin la leche para nuestros hijos, sin sus pañales, sin las medicinas y que nos manipula a través de los medios de comunicación tratando de convencernos de que el enemigo es el estado socialista y popular

…I thought of the long lines for a bottle of milk, for a diaper, for medicine. I couldn't help but think of the suffering and the torture as another form of manipulation exercised by a state to reach its goals […] The thing is, the former capitalist regime in Venezuela still has all its power. The power to leave us without milk for our children, without their diapers, without medicine. It manipulates us through the media trying to convince us that the enemy is the people's socialist state.

Pedro Patiño, from the same site [21], shares a similar vision:

El partido único de gobierno, la hegemonía comunicacional del estado político, la propaganda de guerra por parte de sectores nacionales y extranjeros opositores, el uso de tecnologías para avanzar en la disociación psicótica de los ciudadanos, todo esto nos lleva a decir que esta magnífica novela que está enmarcada en la “Distopía” es decir en la “anti utopía” nos cae como anillo al dedo.

The single government party, the political state's hegemony of communication, the war propaganda run by groups inside the country together with and foreign opponents, the use of technology inducing further all this psychotic disassociation in the citizens… All this leads us to say that this magnificent novel, framed in a “dystopia”, an “anti-utopia” fits us like a glove.

“Big Brother is watching you”

[22]

[22]Photo of a billboard with the eyes of Chávez taken in Guarenas, in the north central part of the country. Image shared by the user The Photographer, published under Creative Commons license CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

In 1984, Big Brother is the supreme leader of Oceania. His voice and face dominate not only the media, but are omnipresent in daily life. Whether he lives or not is not the point, he is the face of the State. Most of those who comment online about the use of Hugo Chávez's image, especially his eyes [23], in posters, billboards, graffiti and even on logos of governmental entities in several Venezuelan cities, agree that this is comparable to the omnipresence of Orwell's Big Brother. This how Pedro Villa sees it [24] on the Contenido Web website:

Los ojos de Chávez se despliegan por toda Venezuela, en todas las instituciones, en vallas, en instalaciones militares y más. Todo con la misma intención que en la novela, decirnos: “Somos el poder y te estamos vigilando”. Lo más tétrico es que en la realidad venezolana el “Gran hermano” vigilante son los ojos de un muerto.

Chávez's eyes are displayed throughout Venezuela, in all the institutions, on billboards, in military areas and more. All with the same intention of [Oceania's government] in the novel, to tell us: “We are the power and we are watching you”. And the gloomiest thing of all is that in Venezuela, the [image] of “Big Brother” are the eyes of a dead person.

The diverse strategies to control information [25] have also been one of the elements that has strongly inspired this comparison to the Venezuelan government. This article from Caraota Digital [26] contains an analysis about the bill to “regulate hate” [27] online. Previous to its discussion the bill was not available to the citizens, and it was supported and later approved by the representatives of the Constituent National Assembly [28] (ANC in Spanish) amidst protests [29] that were questioning, among other things, the legitimacy of the Assembly itself. The ANC was created in 2017 to dissolve the National Assembly, whose members had been voted in elections back in 2015 [30] and were from the opposition in its majority:

La Ley del Odio, recién aprobada por la ANC, cuenta con estructuras que permitirían acabar con los “traidores de la Revolución” […] De igual manera [se prohibe a] los usuarios de redes emitir mensajes que, de acuerdo con la interpretación de la ley, promuevan el odio o la intolerancia hacia un determinado grupo político.

The Hate Law, recently approved by the Constituent National Assembly, provides the means that would permit the government to put an end to the “traitors of the Revolution” […] It also [prohibits] Internet users from sending messages that, according to the interpretation of the law, promote hate or intolerance against a specific political group.

War is Peace

Other similarities not only appear in the interpretation of bills, in speeches or from those in power. The creation of the Vice Ministry for the People's Utmost Social Happiness [31] in 2013 drew a lot of criticism [32] online [32] and sounded familiar to many of Orwell's readers. Changes made to school textbooks, especially in Venezuelan history [33], are another reason for concern. These changes form part of several efforts that seem to have new interpretions on Venezuela's Independence [34], as well as new visions of the life and work of Simón Bolívar, the country's most important national hero. Some of these initiatives have been seen in new investigations [34] about the death of Bolívar and in featured films [35] that recreate his biography.

About this, Veda Everdum from newspaper El Nacional [36] comments:

Los que nacieron de 1980 a 1995 y vivieron en Venezuela saben perfectamente quién fue, qué hizo, y todo lo que «en realidad» pasó de 1998 al 2012 con el gobierno del ex-presidente […] el gobierno oficialista ha empezado, desde que murió el Presidente Chávez, a cambiar la historia, a cambiar el pasado; a pintarnos algo que en realidad sabemos que no fue así.

Those born from 1980 to 1995 and living around those years in Venezuela know perfectly well who [Hugo Chavez] was, what was done and what really happened from 1998 until 2012 under the government of the ex-president […] Since President Chávez's death, the government started to change the history, to change the past, to present us something that in reality, we know to be untrue.

The use of language and the adjectives used by one political group to describe the other also have a place in these conversations. Online authors such as Andoni Abedul, in her Medium space, [37] say:

Esto se puede ver claramente cuando llaman a los opositores [“golpistas”], pero el gobierno celebra el 4 de Febrero, una fecha en la que el ex-presidente [Hugo Chávez] hizo su primer intento de golpe de estado contra el presidente de aquel entonces.

This can be clearly seen when the opposition are accused of plotting a coup d'Etat [used in Spanish as an ever present adjective: “golpistas”], but the government celebrates February 4th, when ex-president [Hugo Chávez] made his first intent to stage a coup against the president at that time [Carlos Andrés Pérez].

Finally, some visions from years ago, pose fundamental questions about labels used by the government. With years of symbols and speeches linked to rebellions and anti-power movements coming from those in power, who are the rebels and who is the power? This how Adam Pervez poses it [38]:

One thing I wondered, though, was at what point does this propaganda stick and just become part of common knowledge, or when does it become ridiculous and embarrassing. Here, a lot of things are labeled “revolution” or “revolutionary”. […] Doesn’t the revolution become the powers that be at some point?