Ghanaian born, South Africa-based architect, novelist and educator Lesley Lokko, during her visit to Trinidad, June 2018. Photo by Mark Raymond, used with permission.

This is the second instalment in our interview series with Professor Lesley Lokko, head of the Graduate School of Architecture at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa. You can read the first post here.

When you think of the role of an architect in society, you might think about the importance of creating a physical environment that's a snapshot of human civilisation. Or about organising space based on needs, aspirations and hopes of a particular culture.

But in societies like the Caribbean, not everyone uses an architect's services — often to their detriment. Why? Lesley Lokko, an architect and writer who recently visited Trinidad and Tobago on the invitation of the Trinidad and Tobago Institute of Architects and Bocas Lit Fest, has an idea.

She thinks this might have something to do with how people perceive the purpose of an architect. Many people do not realise that purpose extends way beyond design and plans — it is connected to a great many other things, including technology and human relationships.

Global Voices (GV): So what is the role of an architect in modern-day society?

Lesley Lokko (LL): I’m always drawn to Spain as a model because I believe it takes in more architecture students per capita than any other country. However, although record numbers of people study architecture there, Spain graduates the smallest number — in relation to the number that its schools take in — who go on to work as practising architects. So architecture is seen as a really interesting, fundamental degree, and even if people go through the full five years, they often go into many other fields that may have something to do with the built environment but not necessarily architecture or design. The mayor of a small village, for instance, might have studied architecture and therefore understands the power and value of a really good piece of civic architecture — so big cities like Madrid and Barcelona are not the only places where projects are happening. Spain is quite democratic in the way in which good architecture or civic space is commissioned.

In the post-colonial world, there's an insecurity around our relationship with education and training that’s just part and parcel of our thinking — so, the attitude generally is, if you start studying architecture, by God you’re going to finish, and then work for a big practice, earn a good living and so on, which perpetuates the idea that architecture is a professional discipline for those who can afford it. I think that’s the complete wrong way to think about it. I run an architecture school now in Johannesburg. It’s the biggest postgraduate school in South Africa, we are now into our third cycle of graduates, and it’s been quite a radical curriculum change. We’ve got graduates now who go off into multimedia, theatre design, web design…things that are sort of spatial, alternative forms of practice. Architecture is a much more lateral, broader, much more diffuse discipline than the way it has conventionally been taught. To make the point more clearly, unlike medical students, for example, who practice on the body of a patient; unlike lawyers, who train with language and rhetoric, students of architecture never build buildings — only representations of them.

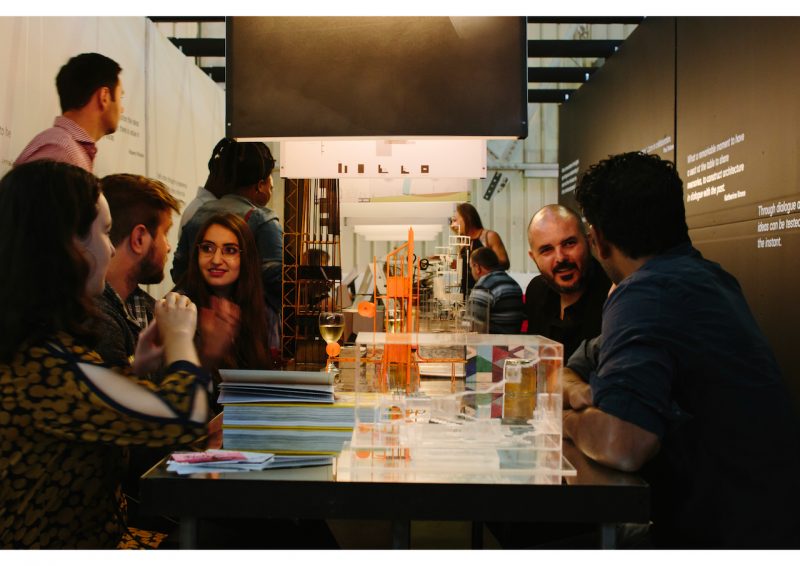

Students of Johannesburg's Graduate School of Architecture during the school's 2017 Summer Show. Photo courtesy Lesley Lokko, used with permission.

Lesley Lokko (LL): Representation, in effect, is almost its own discipline. It’s their language, whether that’s in film, multimedia, photography, collage, montage — the range of visual tools available to students today is almost endless. The historical tools — plans, sections, and elevations — are absolutely vital in terms of instructing someone how to build. But they’re not the only means by which a project can be drawn or represented. To add to the complexity, modern construction methods are their own speciality. If you were to look at the façade of a building today, even as an architect at the top of your game, you’d be hard-pressed to explain how it ‘works’. But just because something is new or modern doesn’t mean it’s without complications and challenges.

Where new means of communication have been very successful — and it goes back to this issue of social media — is in disguising themselves in the language of the old. Facebook uses terms like “Like” and “Friend” — but you are not my friend in the conventional sense of the word. Young people today have less and less sense of the conventional or traditional meaning of words and as a result, their understanding of the world has shifted. When I talk to my students about things like scale and distance and proximity and adjacency, all the architectural terms of my own training, they understand them completely differently. Distance means little to them because they can be friends with someone they've never actually seen who’s 6,000 miles away. They’re used to seeing things on a screen, not in three-dimensions. Their worlds are networked, fluid, mobile, where mine was fixed, grounded, solid. And these terms are still the fundamental terms of our trade. You have to be able to understand things in scale, but if you don’t understand what scale is, because your world has no scale… We’re being altered, somehow slowly, without us even noticing it.

Students of Johannesburg's Graduate School of Architecture during the school's 2017 Summer Show. Photo courtesy Lesley Lokko, used with permission.

GV: How does that affect how you teach the discipline?

LL: The one luxury of education is that it gives you time and freedom to reflect…very different from when you have deadlines and budgets. But I find that very few people are talking really about those things, certainly in Africa. We’re still talking about productivity and efficiency and employability and test results — we’re not really talking about the deep things that I think matter. We operate at such a speed now that those opportunities to reflect critically on what’s happening to us in scale and time and distance and taste are important.

GV: So how does architecture host that relationship between people and environment in a world where technology is such an influence and is changing so fast?

LL: I travel a lot. So when I was packing for this trip [to Trinidad], I left Joburg, went to Paris, Venice, London, Miami, Santo Domingo, here, going to Chicago, back to London, then to Madrid and then I go home. Everything fits in a fairly small suitcase because I know most of the hotels I stay at I can launder a clean shirt; I stick to a palate of mostly black and white because that’ll go everywhere; my clothes are neither too heavy nor too light — so in a sense, my environment is elastic — it’s moving with me. And I'd put on Instagram that I’ve been to Santo Domingo, I’ve been to Trinidad, but I could just as easily cut and paste those images from the internet and no one would ever know. So in a weird way, it’s strange to me that I’m going to travel halfway round the world, but at another level, it’s almost as if I didn’t go. In that construct, my relationships with people become really important. So it’s less my relationship with the environment or even the architecture. I’m looking for more meaningful connections with people that I meet.

We run a very different programme in the graduate school which involves what’s sometimes referred to as ‘cracking’ students open. In a less brutal sense, I’m really interested in what drives them. In a post-colonial context, the majority of students are black — and for me, it’s not so much a skin colour as the fact that they come with emotional relationships to the rest of the world that are different from the white students — through things like history, class, privilege, etc. I don’t want those students to miss the opportunity of being honest. So students need to tell me what really drives them, what they are really interested in, and I will find a way to facilitate that interest. In a lot of the post-colonial world, I would argue that what’s required is a kind of creative therapy because so much of what really drives us is suppressed.

The cover of one of Lesley Lokko's novels. Image courtesy Lokko, used with permission.

GV: What about synergies between writing and architecture?

LL: Architects are narrators. They tell a story through the way in which they manipulate space. That story might be subliminal, but all architecture is storytelling — even more so at the level of student architecture, because you don’t build the building, so whatever representation of it that you have is its own narrative.

For me, writing — because architecture was so resistant to these issues around race, identity, gender, power — writing was actually an easy discipline to deal with because it’s more forgiving. If you think about English literature as a body, it has been so enriched by the post-colonial world. You can’t really think of English literature without that influence — it’s impossible. Architecture is different. It’s historically been really resistant to the idea of ‘difference’ — perhaps less so now than 30 years ago — but when I was studying, if you wanted to talk about race or identity, people would say, ‘Go study sociology, not architecture!’

But I don’t see them as different at all. Someone once suggested to me that I must have an affinity for situations that are neither one thing nor the other and that is connected to childhood. Being half-Scottish, half-Ghanaian, there was a comfort in things that can’t quite be reconciled. When I finished studying sociology, I decided I wanted to be an architect and then I wanted to be a writer, so there’s always been an instinct to move out of something just because I like that tension. And probably now, after so long, I understand that tension is productive. It’s not problematic. But the same impetus is there to tell a story.

GV: You've turned that tension into a tool.

LL: Yes, and I use it in writing and in teaching. To me, my novels were always didactic — all about crossing racial barriers and political histories — and half of the people reading would think it’s a love story. I realised that what you think you’re doing and what other people read into it…you’ve got no control over that.

And I think it’s the same in teaching now — there’s a lot I want to say and I’m saying it through students’ work. And in much the same way that the books go off and do their own thing, so do the students and that’s really satisfying, that there are no conclusions.

In the third and final instalment in this series, we talk about literature, culture and identity.

1 comment

Very well done interview. Professor Lokko is quite interesting.