Dr. Rosaly Lopes | Foto: Divulgação, used with permission.

Rosaly Lopes grew up in a middle-class family in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil watching Star Trek, fascinated by her school’s telescope and following all the news about the Apollo mission. When Apollo 13 had to return to Earth in April 1970, it was the story of Francis Northcutt, the woman responsible for calculating the spaceship's route home, that grabbed her attention.

“Just showing a woman, in Houston’s [Texas, United States] control centre, was a very great inspiration for me,” Lopes said in a telephone interview with Global Voices (GV).

Forty-eight years after the mission, Rosaly Lopes has become one of the world’s most important scientists. Director of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) department of planetary sciences, she entered the Guinness Book of World Records in 2006 for having discovered the most volcanos, recording 71 on Jupiter’s moon while working on the Galileo mission.

Since 2002, Lopes is among those in charge of exploring Saturn’s moon Titan, the second largest in the solar system, with the probe Cassini. It is on Titan that she will begin searching for the possibility of life outside of Earth.

In 2018, Lopes became the first woman to edit the journal Icarus. Created by the famous astronomer Carl Sagan, the journal is a reference point in planetary sciences. She spoke with GV about her projects and the power of seeing women in important roles in science to help future generations.

GV: How did you become the first woman to edit the journal Icarus?

Rosaly Lopes (RL): Carl Sagan started Icarus because at the time there was no scientific journal to publish works exclusively on planetary science. The editors all came from Cornell University because at the time the submissions were all sent there and passed from one professor to another. There were few editors, I think three or four. The last one stayed for more than 10 years. He and the American Astronomical Society, which has a division for Planetary Sciences, started to ask who would like to be a candidate. I presented myself as a candidate and they chose me.

GV: What do you think of the ideas that question scientific data, facts, and research?

RL: It is a small part of the population which think this. But there are people who do not want to believe that it is human activity which is causing [climate change]. This is because there are a lot of people who are afraid that our mode of life has to change. I am optimistic, I think that we will discover ways of using energy that do not cause global warming. The problem is that the question has become more political than scientific.

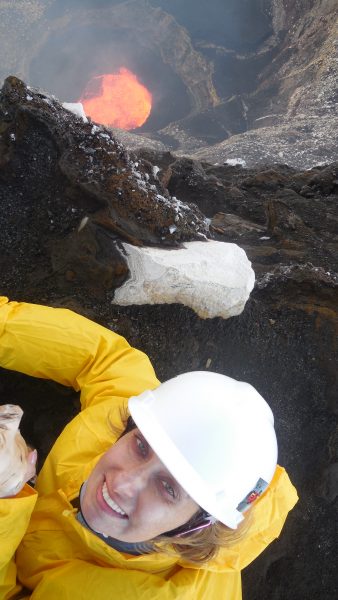

Rosaly Lopes doing research in Vanuatu in the Pacific. Photo: personal archive, published with permission.

GV: In 2005, you received the Carl Sagan medal for your work on inclusiveness in public education, especially for Hispanic youths and women. Could you speak more about your view on this?

RL: Inclusion is important because science needs talent, it needs dedicated people, and it does not matter it they are men or women, of different ethnicities, or anything. It is important to have youths aimed at a career in sciences and technology because it is our future. Medicine is also very linked to the area of technology. Science has to be a field prepared to include all.

GV: For women, they say that the atmosphere in the field of science is more difficult, that they need to prove themselves more. Do you agree?

RL: I think that this is a little bit of a myth. I think that 50 or 30 years ago, yes. But, today, for example, in the area of Planetary Sciences, women constitute 30 or 35 percent. Now seeing a woman scientist is not a thing that people consider ‘different’. From the moment that you have 25 percent women in a scientific area, it starts to be something more normal.

GV: Did you ever encounter prejudice?

RL: No and I never worried much about this. People should not lose time worrying about this. I was always of the opinion that, if somebody has a prejudice, the problem is theirs, not mine. It is better to go forwards and do the work in the best way that you can.

GV: How did you start taking an interest in this area?

RL: I grew up with the Apollo programme and it was that which inspired me a lot. I wanted to be an astronaut, at first, but I saw that I was a woman, Brazilian, and very short-sighted. So, really, it was not going to happen. I decided that I was going to help the space programme as a scientist. I decided this very early and never strayed from this path.

GV: What did your parents think?

RL: Fortunately, they supported me a lot, because without this I could not have taken on anything. My mother was worried that I, as an astronomer, would not have a job. But she made a point of me learning English and French, for me to have a way of earning money, even if the profession did not give me money. They encouraged me a lot such that I studied abroad, they paid for everything, made sacrifices, because they saw that, especially at that time, there was no field of astronomy in Brazil. Now it is better.

GV: Is it common to see people from developing countries in this field?

RL: It is not very common, but it is changing. When I started, really, it was not at all common. But now I am seeing more and more people. There are opportunities, especially if you are very dedicated and study a lot. We need talents working in those areas, so it is important to encourage all the people who really like the field.

GV: A Brazilian magazine referred to you as ‘the Brazilian who succeeded at NASA‘. What do you think of that title?

RL: (laughs) I did not know about that title, interesting. Everything in life is effort and a little luck, take advantage of the opportunities that appear. I took on some risks. At 18 years old, I left Brazil to study in Britain and it was difficult. My English was good, but not excellent for university level and I had difficulties. My preparation in Brazil was lower than the British students, although I had attended good schools. Afterwards, I was in Britain with a good job with the government, I worked at Greenwich Observatory, but decided that it was not what I wanted to do, because there was no chance of doing research. I took a risk, left the job and went to the USA to participate in JPL [Jet Propulsion Laboratory] with NASA, with a scholarship for two years’ duration. Fortunately, it worked out, but it was a risk, because I knew what I wanted. My father said that the most important thing life was to have a passion, go after it and don’t give up.

GV: You participated in the Cassini Mission and became one of the world’s leading specialists in active volcanoes. Which of your projects did you most like doing?

RL: That is difficult to know. I think that my work on the Galileo Mission, on the volcanic moons of Jupiter, was what most stands out even today. But, I hope that my most important work, I have not done it yet. That I still have time ahead.

Photo: Rosaly Lopes from her personal archive, published with permission.

GV: What is your next project?

RL: I just received funding from NASA, a large project of mine was approved to study the moon Titan in more depth, which is a moon of Saturn. We want to do this study with a lot of researchers, spread over all the United States, in Hawaii, Chicago, Britain. We are conducting a study on the possibility of life developing on Titan.

GV: Do you think that we are close to the day when we can live outside of Earth?

RL: This is what we are going to study, not only the biological aspect, which already has a team of biologists in Chicago researching if life could develop in the ocean of liquid water underneath a layer of ice on Titan, but if organic material, which could serve as food for that life, that we know exists in the atmosphere and on the surface, could penetrate the ocean and after, with cryovolcnanism, ice-volcanic activity, if it could come to the surface and we could detect those signs of life.

GV: But do you think that we are close to the day when we could live in those environments?

RL: I am talking about the possibilities of microscopic life, which is one of the fundamental questions to know if life developed in other planets and moons. The possibility of colonization, there are now plans to make a base on the Moon, but I think that will take a long time. If I have an opportunity to go to Space, I will go. My dream of being an astronaut is still there.

GV: Icarus was created by Carl Sagan and he was the editor of it for some time. Did he become one of your references? Who are the others?

RL: I knew Carl Sagan personally, because when I worked on the Galileo Mission, he was also working on it. He did very important things, not only for the field of sciences, but for having been the first scientist who stood out for publicizing sciences in a big way. At the time that he started doing this, with TV programmes and everything else, the majority of scientists thought that it was not a good thing. ‘A scientist should not waste time doing those things’. Carl Sagan broke this barrier. He showed that he could be a great scientist and publicize science at the same time. I always did a lot of publicizing, because I think it is very important to inspire the next generation. He helped me to do this, I won the medal (with his name) for exactly this. There are still people who have prejudices, but it is reducing.

GV: Cosmos [Sagan's 1980 TV show] is still a reference for a lot of people.

RL: It is. But, when I was a girl in Brazil I had not heard of it. There were few books about astronomy at that time. My father gave me ‘The Universe’ by Isaac Asimov, and this was very important. I remember that when I was growing up, there was the mission Apollo 13, which had to return to Earth. The reports of two newspapers that I got in Rio de Janeiro talked of a girl Francis Northcutt. Her nickname was Poppy. She worked for a company for an airspace company, calculating orbits for spaceships and she had been helping the calculations for Apollo 13 to return. Just showing a woman, in the Houston control centre, was a very big inspiration for me. Funny, I never met her in person. She left NASA soon after, went to study law and become a lawyer. It is important for women scientists to raise awareness to inspire today’s girls.