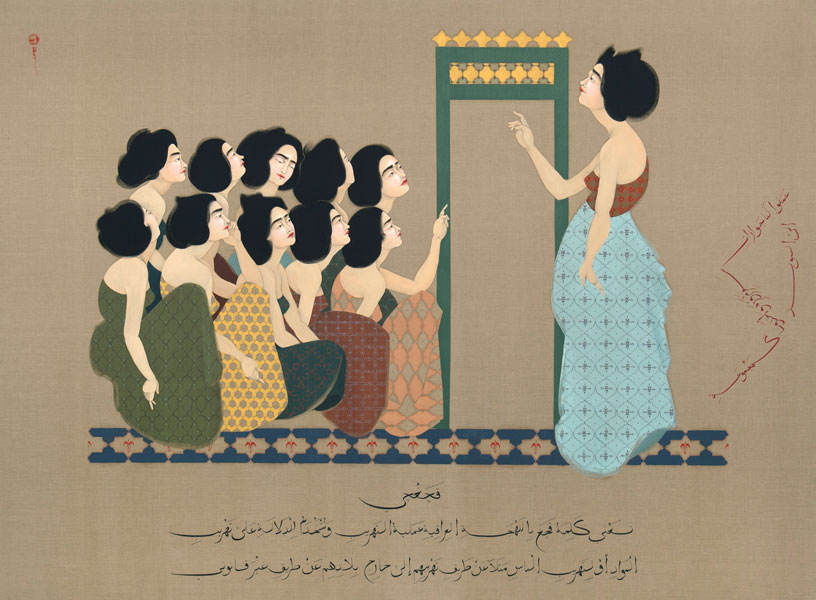

Iraqi artist Hayv Kahraman. Image provided by Kahraman.

When she was 11-years-old, Hayv Kahraman’s family fled the Gulf War in Iraq with only one suitcase. Among essential items, her mother packed a mahaffa, the Iraqi hand-held fan made by weaving the fronds of palm trees. It traveled with Kahraman as she made the journey from the Middle East to Europe, and decorates her family home in Sweden today. “Mahaffa for me is a nomadic object because it’s something that brings me back to the past,” Kahraman tells me at her latest exhibition, “Re-weaving Migrant Inscriptions,” at the Jackson Shainman Gallery in Manhattan. “A different life that doesn’t exist anymore.”

As in her previous exhibitions—“How Iraqi Are You” (2015) and “Let the Guest be the Master” (2013)—Kahraman’s new work is a masterful exploration of the issues of identity, personal struggle, and human consciousness. But this time she has embraced new methods of incorporating objects which carry generations of history into her pieces. Kahraman’s latest exhibition also reveals the evolution in her expression of the images and memories that haunt refugees living in the West.

From her collection, “How Iraqi Are You?” an oil on linen piece called “Kachakchi”. Image from http://www.hayvkahraman.com/ and used with permission.

Kahraman’s use of female bodies in different poses, inspired in part by the Persian and Japanese miniature, could be seen as a celebration of memory, femininity, and liberation. This multi-layered, sophisticated presentation of various complex perspectives, combined with a vivid yet soothing color palette, provides a smooth finish to her method of storytelling. Kahraman’s new work is not only touching, but it provokes lasting thoughts and feelings in any one — no matter their background.

Kahraman’s new exhibition has excelled her art into the territory of excellence in expressing some of the crucial issues of our time through consistently aesthetic and emotionally powerful paintings.

Omid Memarian (OM): Why did you choose to name your exhibition, “Re-Weaving Migrant Inscriptions?”

Hayv Kahraman (HK): I think this whole body of work centers around the idea of memory and how it impacts immigrants and people within the diaspora, like you and me. When I first came up with this way of cutting the linen, it was very intuitive. I didn’t think of mahaffa at the time. I was puncturing the surface. And cutting it was very cathartic.

‘Mnemonic artifact’ one of Kahraman's piece's from “Re-Weaving Migrant Inscriptions”. Image from artist.

OM: The mixing of mahaffe with your art integrated well with the bodies and souls of your paintings.

HK: It was a struggle. I talked to a lot of conservators prior to doing this and I was having so much trouble, because when you cut the linen, it wants to sway and I want to make sure it’s perfectly flat. How do you repeat the surface, the cuts, in order to maintain the integrity of the structure? I did a lot of tests. As you can see, I have two studies that are hanging. In two of the works, I wove actual palm tree fronds from California. And I found out the other day—or maybe it’s a known fact and I didn’t know about it—that California imported the seeds from Iraq and the Middle East from the palm tree. It was a very interesting parallel for me.

OM: You focus on mahaffa in different forms and shapes in your current show. It’s one of the items that your family put in your luggage when you left Iraq. It seems to me that by incorporating it into your work, you are injecting something from the past and making it eternal.

HK: Exactly, I think that’s the whole point of it, that as an artist I archived these memories that I feel I’m kind of losing, and in a way, those memories are supposed to identify who I am. Which is also really problematic because, who am I? I’m not Iraqi. I am, but I’m not. I’m not American, but I live here. I’m not Swedish but I have a Swedish passport. So it’s really problematic. It marks that point of displacement for me. That was the time when my biography, my identity was interrupted: when I fled. I’m no longer that person. I’m somebody else. So, if I were to apply a word to it, the mahaffa, it would be “displacement.”

OM: How do you convey the nostalgic relation between “things” and “objects” that attach migrants to their past and roots?

HK: Language would be one of the ways. Calligraphy is a medium through which you can access language or the loss of language; forgetting about your mother tongue, recovering it and trying to access a connection to it somehow. Because I don’t speak Arabic anymore, and I don’t have any family here in the United States. I have a daughter, but she was born here. I think the main thing is that notion of loss, the trauma of that loss, and manifesting that through a painting becomes the struggle. For me, personally, in my studio, how do I make this come across? With the technique of cutting the linen and the weaving and connecting it to an actual object like mahaffa…

This piece illustrates the ‘weaving’ of materials that Kahraman incorporated into her work.

OM: Female hair has a strong presence in your work. What does hair symbolize for you?

HK: I think you know more than anyone, it’s such a contested thing, especially in the Middle East. You like your hair and all those associated feelings. Women being hairless. Not being a hairy Arab, which I am. Hair was a very natural thing for me to work with. I didn’t necessarily think about what it represents. It was very intuitive. When I think about it now, after the fact, it’s because it is such a contested bodily thing in my culture, and even all around the world.

OM: The images in your paintings of disfigured female bodies and faces are very powerful in depicting the experiences of women. What’s your thought process in defining and drawing female bodies?

HK: It starts by posing with my own body; I pose in various positions in my studio. The poses then transform into sketches and then they become paintings. There is always some sort of performance that’s happening.

They [the women] are always doing something on the linen, performing something. For this show, I really wanted to let go of control… That’s the origin of how they come into being…

OM: You have spoken about the connection these bodies have to a “painful journey.” What’s underneath all these different poses?

HK: It’s funny because I started painting when I was in Florence, Italy. And I was really in that mode of renaissance painting, going to museums and making copies, and I felt and believe that this is what I was striving for. That’s when she was born. That’s when I started painting her. It came from that colonized space. A space where somebody was brown, was thinking that these white figures are what I want to aspire to, to paint, in order to succeed. When I look at them now, I am reminded of that. That’s why they have that white flesh. And that’s why I’m in constant dialogue with them, or at least feel like I am.

On the painful journey, I was born during the Iran-Iraq war, I lived through the first Gulf War. These are permanent scars on your body. You carry these memories. That definitely comes through in my work and I deal with it every single day. It’s like you are in this PTSD mode and you are trying to figure out how the hell you can survive.

Women walking around with sacrves with the texture of the “mahaffe” from “Re-Weaving Migrant Inscriptions”.

OM: There is a very close connection in your work between the faces that embody so many details and Persian miniatures. Even the colors on the faces are more distinct and alive. First, how do you describe or understand sexuality and femininity in Persian miniatures, and why use this form of expression?

HK: That’s a good question because the faces are the most fun part to paint. The Persian miniature is definitely an inspiration in terms of the color scheme. For me, when it comes to the body and expression of the face, I’m more connected to Maqamat Al-Hariri [13th century Arabic manuscript]. In Maqamat, you don’t have the beautiful elaborate backgrounds that the Persian miniatures have. The focus is on the figure and the face and expression. That’s where I draw inspiration from in terms of depicting the faces.

OM: There is a sense of freedom and liberation in the way women interact with each other in your paintings, the way they touch and look at each other or look into space. How much of that is from your personal experience?

HK: My earlier work was overtly violent. You have female genital mutilation, you have women hanging themselves, really violent, even like didactically so in your face. It reflects what I was going through at that time in my life, particularly in my personal relationship. I was in an abusive relationship at the time. The work was an outlet for me to investigate what I was going through. And I didn’t realize what was actually happening then. That’s the crazy part. It was very therapeutic. It probably started as a therapy or an outcry. And it was years later, when I got out of that relationship, that I could look back and say, that’s why I was doing what I was doing.

OM: What connects you to the root you belong to?

HK: I struggle with that, to try to find those connection. I think the only thing is either going back to the Middle East, physically traveling there, or just being with my family. Food with my family (laugh) And of course research based stuff.