Images remixed by Oiwan Lam.

In September 1987, a Beijing laboratory sent what became China's first email. The message, to a German university, read: “Across the Great Wall we can reach every corner of the world.”

The development of internet infrastructure in the past few decades has enabled Chinese people to continue crossing the “Great Wall” and communicate with the rest of the world. But Chinese authorities soon threw up another wall to prevent the people from accessing information they deemed threatening to the Chinese Communist Party.

In 1996, Beijing enacted a set of interim provisions for governing computer information, and in 1998, the Ministry of Public Security launched the Golden Shield project — a national filter that blocks politically sensitive content from entering the domestic network.

This censorship tactic scheme has long been nicknamed the Great Firewall, and has undergone periodic upgrades since it was first introduced, given that people's efforts to cross the Great Firewall have been non-stop. Some describe the interplay between the Great Firewall and Chinese netizens as an ongoing “prison break”.

Recently, Hong Kong-based investigative journalism platform the Initium reviewed the concurrent evolution of the Great Firewall and tools used to circumvent it. Below is a summary and partial translation of key points in the Chinese report.

First stage: The Golden Shield blocks domain names and IP addresses

The first generation of the Golden Shield was a domestic filter that blocked specific domain names and server IP addresses:

「牆」就像一個邪惡的郵差,只要看到你的信封上寫上 Google 或 Facebook 等網站的地址,就會直接將信件丟棄。

The Great Firewall is like an evil mailman; whenever he sees Google or Facebook addressed on the envelope he will just toss the letter away.

By using an overseas server, i.e. a proxy server, people could still go around the wall and visit any sites they wanted:

就好像你將一封希望寄給 Google 的信,先寄給一位認識好郵差的朋友,再由他幫你轉寄給 Google。

It is like you plan to send a letter to Google; you can first send the letter to a friend who knows a nice mailman and then the mailman can forward the letter to Google.

Second stage: The Golden Shield implements keyword censorship

The keyword-filtering system of Golden Shield was upgraded to detect the content of the websites that netizens visit, even if the internet connection is going through a proxy. If there is “sensitive content” communicated along the network connection, the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) is reset:

這時候,「牆」就如一名資訊審查員,拆開你的信件,只要發現你提到敏感資訊,便將你的信丟棄。

In this case, the Great Firewall acts like an information inspector; it can tear open your letter and toss it away if sensitive content is found.

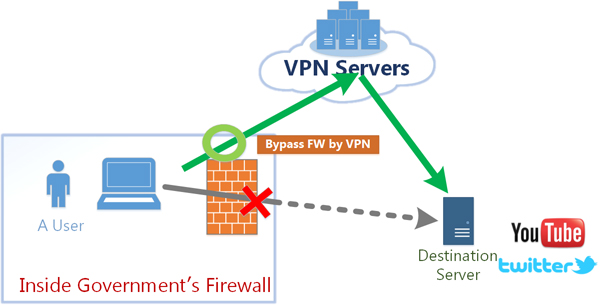

To prevent such inspection, Chinese netizens started using virtual private networks, or VPNs, to bypass the Great Firewall. Originally, VPNs were used by global corporation to protect business secrets; their internal communications traveled within a private network and were encrypted to make sure that no third party could detect the messages sent through the network.

In other words, a VPN server outside China could safely transmit a Chinese netizen's visit requests to any third-party website.

Third stage: Great Firewall begins detecting VPNs and other circumvention tools

With support from the government, the developers of the Great Firewall finally managed to identify weaknesses in VPNs. They found that there are some obvious features of the commonly used VPN protocols, such as IPSec, L2TP/TPSec and PPTP, which often use specific ports. When processing the encrypted connection, it leaves a distinctive trace.

Again, the Great Firewall was upgraded to detect such “irregular” connection traces:

這就好比「牆」雖然看不懂你的信件,但能從你信件內容中經常使用的筆跡和標點符號出現頻率,分析出你的真實意圖。

It's like even if the Great Firewall can’t read your letter, it can analyze the intention of the letter based on the handwriting and how often the punctuation appears.

In 2011, the Great Firewall blocked two major VPN protocols, PPTP and L2TP, temporarily. But the economic damage of blocking protocols was huge. The Great Firewall since has been upgraded to slow down or reset individual VPN connections.

To solve the problem, open source developers from Github collectively developed a new tool, Shadowsocks.

Same as a VPN, Shadowsocks is circumvention technology. It encrypts communication between the user and the website they wish to visit, but the connection is hard to detect for third party because Shadowsocks allows users to choose different encryption methods and appoint a random port.

Moreover, Shadowsocks is an open-source project, so even if the original developer were to delete the codes published at GitHub under pressure from authorities, other developers could carry on the development and maintain variants such as ShadowsocksR and V2Ray.

As the Chinese government has blocked more and more websites, including non-political online game sites, photo-sharing sites and social media platforms, the demand for circumvention tools has grown. Some individual developers have build successful businesses by providing circumvention apps to individual netizens using Shadowsocks.

After Apple upgraded its operating system to iOS 8 in 2014, the company's devices started to open VPN-related API programming ports, which enable other developers to build privately-owned encrypted VPN apps. Since then, proxy apps supporting Shadowsocks protocols have flourished. People need only to install and open the app and they can connect to websites banned by the Chinese government, making it easy for casual internet users to access websites outside the Great Firewall.

But Chinese authorities are keeping a close eye on all of this.

Fourth stage: Cyber security laws target anonymity and VPNs

In addition to constantly upgrading the Great Firewall, Beijing has also introduced new laws to criminalize VPN service providers.

On January 22, 2017, the Chinese Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) announced a “Notice on Clearing Up and Regulating the Internet Access Service Market”, which states:

without approval by the telecommunication management departments, one must not create on his own accord, or hire, dedicated lines (including virtual private networks VPNs) or other information channels to conduct cross-border business activities. Basic telecommunication enterprises leasing dedicated international lines to users, should create a centralized user archive, and make clear to the users that the terms of use of those lines are limited to internal office use, and that the lines must not be used to connect to domestic or overseas data centers or operations platforms to conduct telecommunication operations business activities.

On June 1, the controversial “Cyber Security Law” officially took effect, giving far-reaching rights to the supervision department, strengthening internet operator responsibilities and duties, and demanding real-name registration of individual internet users. The monitoring system is similar to the “pre-crime” operation in the US science fiction movie “Minority Report”.

The legislation directly compelled Apple to take down VPN apps from its China app store in July. Amazon's China partner also issued a warning to its customers against the use of its cloud server for setting up a VPN server. It said that once they discover clients using unapproved VPNs, it would shut down their services.

The pressure directed towards individual developers and users of VPNs is severe. Starting in July, news of police harassment of proxy software developers and proxy software users has appeared regularly.

One developer shared on Twitter on how he was identified by the police. He said the police located his IP address through his QQ number which was shown in the App store. The police visited his apartment and forcefully demanded that he remove the app. He later vowed not to upload his proxy app again.

In Shenzhen, some internet users have been located by the police due to their frequent connection to proxy software. Their internet connection service was cut and they were forced to write a letter promising they would never use the software again to resume the connection.

These increased crackdowns have frightened individual circumvention tool developers and users. Among the developer community, one developer said they are left with two options:

要絕對安全,只有兩條路:一個是不做中文版,包裝成類似 ExpressVPN 這樣的海外公司;另一個……我前天見了一個朋友,他說他認識工信部的人,可以幫我申請 VPN 銷售許可證。這樣就可以徹底洗白了。

There are two ways to go to be absolutely safe, one is by not making the Chinese version of the app, and promoting your app as if it’s from a foreign company like Express VPN; and the other way… I met a friend a few days ago, he said he knows someone who works at MIIT and he can help me get a VPN sales permit. In this way, the business can be totally legit.

However, getting a license means working with the government to spy on VPN users’ online activities. The developer further explained:

肯定要按官方要求,記錄用戶身份,保留用戶日誌,到時候上面如果查下來,要什麼數據就給他們。…其實沒幾個用戶在意隱私的,他們只要能翻牆就行了。而只要有人用,我們就有錢賺……

Of course you have to follow the government rules to register user identity, keep login records; and we will have to give whatever data the government requires in the future…actually few users care about privacy, what they want is to just get over the wall. As long as we have users we can make money…

Technically speaking, circumvention technologies have outwitted the Great Firewall. Yet the new legal regime has changed the rules of the game. Today, Chinese netizens who want to be connected with the external network must choose to either give up their privacy and subscribe to licensed VPN services or overcome their fear of police harassment and register with overseas circumvention tools.

After three decades, the dream of crossing the Great Wall and reaching every corner in the world has given way to a nightmare which sees people's freedom under threat.