[1]

[1]Locals refer to this building on the outskirts of Addis Ababa as “Steal Display.” They allege a mid-level government official openly looted public funds to build it. Photo sourced from Syoum Teshome's blog [2].

Last week, the Ethiopian government announced the arrests [3] of ‘top officials’ accused of ‘misdirecting public funds’ to ‘maximize their private interests,’ employing favored euphemisms for corruption. The names of those arrested were held back until later in the week, however, with one writer [4]on Facebook comparing the delay to a suspenseful drama series.

Ultimately, when a state-backed media website revealed [5] the list of ‘top officials’ as 48 junior government bureaucrats, middlemen and investors, the news was less groundbreaking.

On Twitter, some complained that the government had overhyped the corruption story with ‘breaking news,’ noting the list of names released did not include a single top official.

Ruling party affiliated FanaBC reported detention of top officials who are suspected of corruption in #Ethiopia [6]. Names aren't mentioned yet.

— BefeQadu Z. Hailu (@befeqe) July 25, 2017 [7]

The highest official called out so far is the former chief executive officer of Capital Roads Authority (Addis Ababa), a position that is nowhere near as powerful as claimed by government media.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn launched [8] a highly publicized campaign targeting government and state-owned company officials suspected of corruption. The campaign has led to the arrest and prosecution of hundreds of officials since January 2017.

Even though the government regularly publicizes these kinds of corruption cases, it has not convinced Ethiopian citizens of its sincere interest in ‘cleaning house.’ According to Transparency International’s most recent Corruption Perceptions Index [9], Ethiopia is listed among countries whose public perceive the pervasiveness of rampant corruption [10] in the public sector.

Online public cynicism regarding the ongoing anti-corruption campaign shares an overwhelming opinion summarized in Seyoum Teshome's blog [2]:

There are practically no non-corrupt officials. Those arrested are corrupt, and most of the top officials who are leading the anti-corruption campaigns are also corrupt. There’s no difference between the corrupt and non-corrupt officials. The only difference is that those who were arrested have not secured the loyalty of senior functionaries that can shelter them.

One factor fueling [11] public cynicism is that infrastructure projects are often delayed or stagnate while contractors, subcontractors, and government cronies grow wealthier.

Arresting and prosecuting junior officials won’t change anything said Seyoum Teshome in a post [2] on his widely circulated blog.

Another writer on Facebook recently pleaded with the Ethiopian government to stop the anti-graft campaign. He sarcastically warned that if authorities do not stop, Ethiopia will soon become a stateless society. In his view, Ethiopian corruption has permeated [12] so many fields that it is a feature of the Ethiopian condition.

The pressure to launch an ongoing anti-graft campaign was driven by protests that began in Oromia, Ethiopia’s largest region, over alleged expropriation of farmlands around Addis Ababa. Tsegaye Ararssa wrote [13]:

“Who said that the Oromo demands are about arresting a select few corrupt and depraved officials or their (questionable, because nepotistic) connections? The indictment of the #OromoRevolution [14] is directed at the system, not some junior officials, or their wives, whom the system is disposing of as collateral damage in its combat with the Oromos.”

Corruption and Ethnic Politics Intersect

Some observers believe Ethiopia’s crackdown on a few mid-level officials is politically motivated. Many have complained about the discriminatory application of Ethiopia’s anti-corruption laws.

Such kind of charges have been used to settle within-party division in the past.

— BefeQadu Z. Hailu (@befeqe) July 25, 2017 [15]

Ethiopia is a one-party state in which the ruling Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) monopolizes power. The EPRDF, however, is a coalition of four ethnic-based parties. The four parties purport to represent particular ethnic groups, but they share the same ideology, political association, and policy preferences.

Authorities from these four parties – Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM), Oromo People's Democratic Organization (OPDO), Southern Ethiopian People's Democratic Movement (SEPDM) and Tigrayan People's Liberation Front (TPLF) – are currently Ethiopia’s top leaders. However, the TPLF is the core of the EPRDF, holding absolute power over the last quarter of a century.

In terms of representation, Oromos make up 35 percent of the country’s 100 million people, Amharas account for about 30 percent of the population and the Southern Ethiopian region accounts for 14 percent. While Tigrayans represent only six percent of the population, they are among the most high-ranking military officers who control the nation's security.

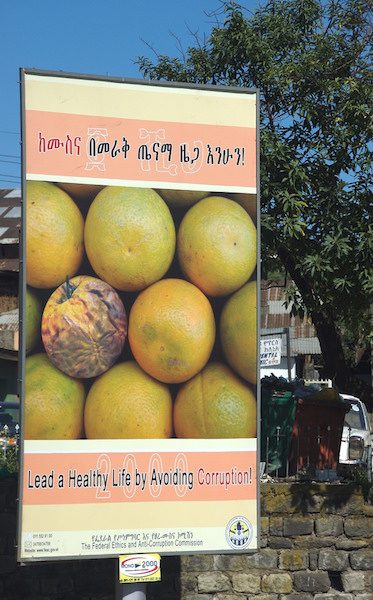

Outdoor advertising campaign billboard against corruption. Photo by Alan via Flickr. CC BY 2.0

The TPLF makes vast fortunes through the Endowment Fund for the Rehabilitation of Tigray-EFFORT [16], a party- affiliated conglomerate with business interests in various sectors (mining, manufacturing, service, and media), while the remaining three ethnic parties participate as a ‘patronage network,’ trading the needs of their people for political influence.

One commentator has noted [17]that while the EPRDF frequently targets non-Tigrayan party members, they often spare Tigrayan senior members despite their alleged guilt for much more egregious corruption.

During the reign of the late prime minister Meles Zenawi, some core members of TPLF were imprisoned for corruption even though many believe [18]they were likely locked up because of a power struggle.