[1]

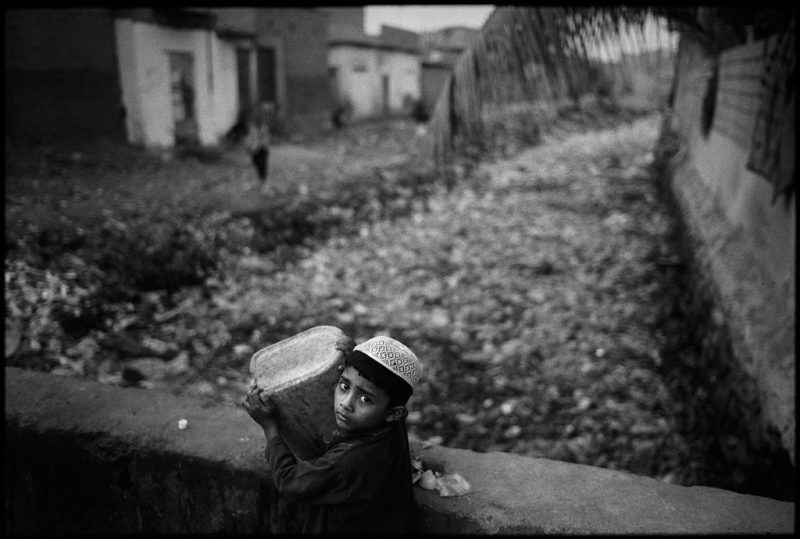

[1]A young boy dumps household waste into the main sewage canal in Karachi's Machar Colony, Pakistan. The slum is an illegal settlement and its inhabitants have no alternative way to dispose of their garbage. By Flickr user Balazs Gardi. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Earlier this month Irfan Masih died after doctors refused [2] to treat him at a small rural government hospital in Umerkot [3], Pakistan.

Irfan Masih was a sanitary worker who had been brought to the hospital after falling unconscious while cleaning his town’s central sewer. Allegedly, the doctors on duty refused to treat him because he was drenched in sewer sludge and hence “unclean”. Irfan's mother explained to news outlets in Pakistan that the doctors were fasting for the Islamic holy month of Ramazan and they believed that even touching, let alone treating, the dying man would break their fasts. So they let him die.

This incident hits at my identities as a humanitarian, a global public health advocate, a medical doctor, and a Pakistani minority. There is much to be said about the shocking levels of prejudice and insensitivity that allowed this tragic act to occur. But what is much worse is that with regard to the sanitation infrastructure of almost all of Pakistan, this prejudice is systemic.

Since Pakistan’s inception as a nation in 1947, the job of entering the country’s gutters to unblock and maintain the invisible sewerage networks that lie under all our feet have been performed by sanitary workers such as Irfan Masih, who come from the underprivileged—and otherised—Christian minority.

Thirty year old Irfan Masih fell unconscious along with three other sanitary staff while cleaning a manhole in Umerkot, one of Pakistan's most religiously diverse [4] cities. He died at the hospital in Umerkot, while the three other workers — who were also Christian — were sent to bigger city hospitals for medical treatment.

Part of the problem lies in the systemic prejudice evidenced in Irfan Masih’s death. But part of it also lies in a point highlighted in a letter written [5]by the Chairman of the Pakistan United Christian Movement, Albert David. “Over the years,” David writes, “score of sanitary workers have lost their lives all over Pakistan whilst trying to clear the blocked gutters caused by irresponsible behaviour of citizens and ill-planning of city governments.”

As Pakistanis, our collective excreta are flushed out of our homes into the underground system, which the sanitary workers are employed to maintain. Their jobs are dual: firstly, to clean the sewerage system—with little to no protection, no gear, no acknowledgement of occupational hazards and no provision of healthcare. Secondly, this regular cleaning is also meant to maintain a functioning sanitation system. These two activities allow Pakistani planners and politicians to avoid any investment in the actual physical engineering system—its layout, planning and setup—as part of the overall sanitation system.

Every human community, whether a small settlement or a massive metropolis, has a water management system with three facets: water sources, which lead into water supply systems, and end in water sanitation.

Water constitutes the very essence of our life, in that we need to consume water in order to survive, as well make use of it in many of our fundamental daily activities. We also need water to dispose of and return some of the end products, both domestic and industrial, of our basic bodily processes. The act of disposing of waste with water breaks it down and causes it to release elements that go on to create the building blocks of life, hence closing the loop. We begin our lives by taking from water and end our lives by giving back to water, as well.

From the Pakistan United Christian Movement Facebook [5]page.

The specific sanitation activities referred to in Albert David’s letter forms the most fundamental basis of modern human infrastructure. Without a means to safely dispose of our urine, our bodies would rapidly acquire acute and chronic diseases, and eventually die as we rotted in our own excreta. Consequently, were Christian Pakistanis not performing the task of regularly clearing our sewage system, the rest of society as it currently operates would come to an end.

In Pakistan, however, the final part of the sanitation loop is currently being taken care of by ageing, ineffective public infrastructure, whose failings are compensated for by the labour of a systematically oppressed community who have long worked in that field.

Few Pakistanis take note of this situation. This apathy is likely rooted in the belief that Muslims are too clean and pious to have to maintain our own sewers and clean our own gutters. This then has a knock-on effect on other aspects of the idea of ‘sanitation’, that also refers to the maintenance of hygienic conditions through services such as garbage collection and wastewater disposal.

The next logical step for me as a humanitarian crisis researcher is to help raise awareness about the importance of occupational health hazards within our society. It is incumbent on civil society to come together and advocate for our current local governments to adopt basic occupational health and safety measures, as well as upgrade our civil infrastructure.

As Pakistani Muslims, we need to acknowledge that our fellow citizens have been working in precarious and insecure situations to clean up our waste products, and sicken and eventually die as a result of exposure to our shit and piss. If our sewerage systems were better planned and maintained, we would literally be a happier and healthier nation.

Is it not outrageous that a death as preventable as Irfan Masih’s, which arose out of a mixture of prejudice but also the failure of systems and lack of public health awareness, should have occurred? A death which would not have happened had we applied public health standards in our urban planning and civil engineering? A death which could have been prevented had we sought to understand sanitation systems and made public health awareness a basic part of every curriculum? A death, which could have been prevented if each one of us understood that clean water will become a coveted commodity as the effects of climate change take their toll?

We as Pakistani Muslims need to check our privilege and acknowledge that we have outsourced a basic social function on the basis of religious identity, to the same group of people that we then let die because they are too ‘unclean’. Until we learn to appreciate the vital role they have played for the last 70 years, and figure out how to stop this particular abuse, we won’t be able to make any greater change.

But before we do so it might be helpful to consider what is taking place right now, below our own streets.