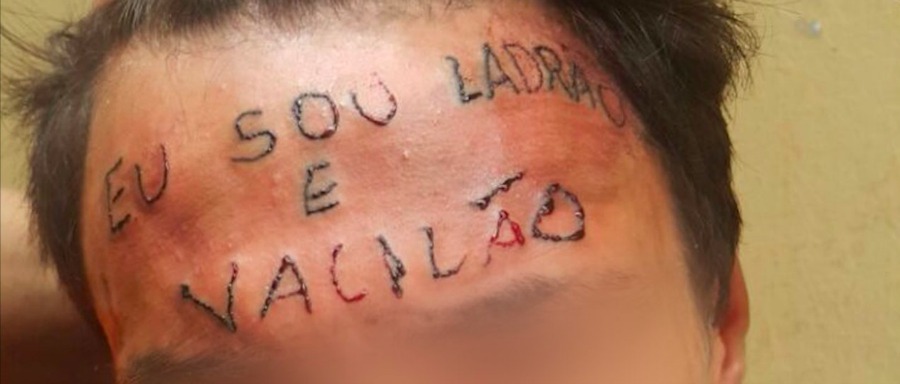

Two men tied the teenager to a chair and tattooed onto his forehead: “I am a thief and scum”. Image: Screenshot from WhatsApp

The story taking over Brazil's social media recently doesn't involve the country's dramatic politics, but a teenager, a tattoo, and two men trying to take “justice” into their own hands.

After hearing rumours that someone had tried to steal a bicycle in their neighbourhood, a tattoo artist and his friend believed they had identified the culprit: a 17-year-old boy. The pair then decided to teach him a lesson. They rented a room in a boarding house, tied the boy to a chair, and proceeded to tattoo on his forehead the sentence “I am a thief and scum”. The entire gruesome ordeal was captured on video and posted on WhatsApp. It soon went viral.

The teenager, who according to his family struggles with mental illness and drug abuse, had been missing from home since the end of May. His parents only found out of his whereabouts after recognising him in the viral video. They alerted police to the footage, who proceeded to arrest the two men and charge them with torture.

After reuniting with his family, the boy denied the accusations of theft to the police. He claims he never tried to steal the bike, but only bumped into it while drunk, and it fell. He also told a reporter [1] that he “wanted to die after seeing the tattoo on his face”.

But a significant portion of the internet didn't express sympathy for the boy. A university project that monitors the political debate on Brazilian social media [2] showed how many of the reactions were actually in support of the vigilantes.

When someone set up a crowdfunding campaign [3]– eventually successful — to help the boy and his family pay for tattoo removal, they started receiving threats on social media for trying to help “a criminal”.

One of the most circulated images on Facebook over the weekend of June 10 — now with over 100,000 shares — said: “When a criminal is punished it becomes news, people think it’s absurd and try to raise money to pay for plastic surgery for the ‘tortured’ minor. But when a police officer dies, nothing happens!”

It was shared by Brazilian Facebook groups such as Right Wing Conservatives [4], Right Wing Lives 3.0 [5] — a name likely revealing of how many times the page had been banned from Facebook — and Admirers of Jair Bolsonaro, [6] which refers to a Brazilian lawmaker who American journalist Glenn Greenwald's The Intercept called [7] “the most misogynistic, hateful elected official in the democratic world”.

Even after it was reported [8]that the tattoo artist himself had previously been sentenced to five years in prison for theft, those pages — who together amass more than 1 million followers — held fast to their support for the vigilantes.

A crowdfunding campaign was created to help the teenager with the removal of the tattoo

Bolsonaro, famous for his passionate defense of Brazil's CIA-backed military dictatorship that lasted from 1964 to 1985, is one of the main voices of a rising movement in Brazil that believes human rights are to blame for the high crime rates in the country.

Last year, a poll by the Brazilian Public Forum of Public Security found that 60% of Brazilians agreed with the phrase “a good criminal is a dead criminal [9]” — for them, human rights only exist “to protect” criminals.

Bolsonaro has been leading in the polls ahead of the country's 2018 presidential elections, doing especially well among the middle-upper classes.

‘A very dangerous scenario’ for human rights progress

Street crime in Brazil is rampant. If you have a group of Brazilian friends, it wouldn't be surprising if nearly all of them have experienced some sort of violent mugging at least once. This reality contributes to a widespread perception that the state isn't capable of enforcing law and order and it depends on the people to find justice for themselves.

No wonder, then, that Brazil is a leading country in lynchings. According to José de Souza Martins [10], a sociologist who authored the book “Lynchings – Social Justice in Brazil”, Brazil has an average of one lynching or attempted lynching every day.

In 2014, two stories captured national attention. First, a teenage boy was stripped naked and had his neck locked to a lamppost [11] with a bicycle chain in Rio de Janeiro, allegedly after he had tried to mug a pedestrian. Only months later, a woman was killed by a mob in Guarujá, [12] a city near São Paulo, motivated by an internet rumour that claimed she had kidnapped children.

At the core of those lynchings is a rejection of basic human rights like the right to life, dignity, and a fair trial — including those who have committed crimes. And as in many countries nowadays, there's an increasing trend in Brazil to frame human rights as something that belongs to the political left, which in itself would render it deserving of opposition.

In an interview with Nexo Jornal [13], Renato Zerbini, who has a PhD in law and international relations, explains how the universality of human rights principles — one of its founding aspects — is right now threatened worldwide:

Em um momento onde o senso comum, produto dessa disputa ideológica, indica que os direitos humanos protegem somente os presidiários, os pobres ou os migrantes não documentados, evoca-se um sentimento de autoproteção nacional e social capaz de arregimentar todos aqueles temerosos da afirmação desses direitos.

Essa ação-reação encaixa-se como uma luva no atual cenário internacional: conflitos armados, enormes fluxos migratórios, instabilidade política, terrorismo, destruição ambiental, corrupção e fanatismos de todo tipo —ideológicos, políticos e religiosos — que tendem a se misturar. É um cenário muito perigoso porque pode corroer e até destruir, em parte ou no todo, o regime de proteção dos direitos humanos e do meio ambiente construído depois da Segunda Guerra Mundial.

In a moment where common sense, a product of this ideological dispute, indicates that human rights only protect prisoners, the poor, undocumented immigrants, it evokes a sentiment of national and social self-protection capable of gathering all those who fear the affirmation of those rights. This action-reaction fits like a glove in the current international scenario: armed conflicts, huge migratory flows, political instability, terrorism, environmental destruction, corruption, fanatics of all kinds — ideological, political and religious — who tend to blend together. It is a very dangerous scenario because it can erode and even destroy, partially or as a whole, the regime of protection of human rights and environment built after WWII.