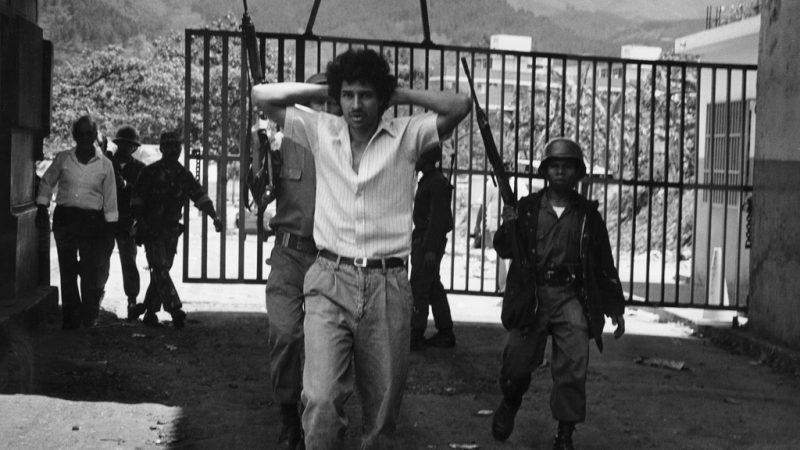

Photo: Francisco Solórzano. Shared by Bernardo Londoy on Flicker through a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

February 27, 1989 and the week that followed, dates which are seared in the memories of many Venezuelans, are widely considered a watershed moment in modern Venezuelan history. It was then that a series of riots, looting and shootings took place, leaving hundreds dead, in what became known as El Caracazo or El Sacudón, a name that has been loosely translated as ‘“the Caracas smash” or “the big one in Caracas”.

The riots grew out of protests in Caracas in response to government policies that would have translated into a steep increase in prices for gasoline and public transportation.

February 27 marked the 28th anniversary of El Caracazo, bringing with it so much discussion that it was one of the main trending topics in Venezuela's Twitter. People shared memories of the riots, and pro-government and opposition users traded barbs, saying El Caracazo was either the beginning of today's political divisions or the awakening of a popular movement against oppression:

28 años del estalllido social “El Caracazo” Movimiento popular que surgio en rechazo a las medidas economicas impuestas!! #27FPuebloRebelde pic.twitter.com/uoYhme0V2Y

— lili’ (@lilidiaz8) February 27, 2017

28 years [have passed since] the social explosion [known as] El Caracazo. A political movement born out of rejection of imposed economic policies. #27FebruaryRebelPeople.

El Caracazo no fue un estallido social, fue una oportunidad manipulada para que la anarquía abonara el terreno para sembrar el chavismo!

— David ® González (@drg2000) February 27, 2017

El Caracazo wasn't a social explosion. It was an manipulated opportunity so anarchy could prepare the field to sow chavismo.

The “spasm of chaos that changed Venezuela forever”

The background, causes and consequences of El Caracazo are still today an important topic of discussion and study. Given the influence of the riots on Venezuela's contemporary history and crisis, the collective site “Caracas Chronicles” devoted a series of posts remembering, explaining and analyzing the “1989 spasm of chaos that changed Venezuela forever.”

Three posts of the series have been devoted to explaining what El Caracazo was, and the place it has in today's political discourse. In them, Rafael Osío Cabrices and Cynthia Rodriguez put together references and testimonies that try to understand the before, during and after of the riots:

[Former Venezuelan president Carlos Andrés Pérez] ran on a promise to make Venezuela great again, after five years of economic decline and corruption scandals […] Those who voted for him expected another consumerist orgy like the one Venezuela enjoyed during his first administration in the 70s. It wasn’t to be. Though oil prices were about the same that in 1977, the national debt was twice the size of the international reserves, and there were many more people around.

Many of ex-President's Carlos Andrés Pérez measures were highly controversial, but the one that set fire in the streets was the elimination of gasoline subsidies. As mentioned above, this made gasoline and public transportation costs rise dramatically, provoking protests in and around the capital:

We call it El Caracazo because the capital was the main theater and the main source of victims. However, starting at noon on Feb. 27 the contagion reached dense commercial areas in [cities surrounding the capital]. Police, [the National Guard] and DISIP [the National Directorate of Intelligence and Prevention Services] were unable to stop violence also there […] By the morning of Feb. 28, looters were at ease in western and central Caracas. Clearly outnumbered, the [Metropolitan Police] seemed paralyzed, thus the riots spread. No political leader was conducting the violence. Some streets and avenues in Central and Western Caracas were blocked by barricades or burning buses and trucks. It was a feast of rage and also joy, desperate poverty and pragmatic opportunism. Police and soldiers were there, but doing nothing; they were waiting for orders. Meanwhile, from the barrios in the slopes of the mountains surrounding the Caracas valley, the poor descended in masses. Finally, the prophets of disaster were right: “el día en que bajarán los cerros” [the day the slums will come down to the city] had come.

The series also presents a comprehensive analysis on one of the reports produced by PROVEA, a Venezuelan NGO that promotes human rights and documents violations. Their work with victims of El Caracazo has brought to light new findings on abuses committed by the police and the military:

Most deaths during this period were caused by high caliber bullet wounds located from the waist up, occurring at night during the curfew. According to reports by victims’ relatives, the military tactic prevalent in popular areas of Caracas […] was indiscriminate fire against apartments and houses, many of which were completely destroyed, in response to a few snipers.

About the number of deaths, the report says:

The official figure of 276 fatalities was reported by the then Prosecutor General, although that institution hadn’t made an exhaustive investigation on the matter. Official secrecy, limitations imposed on the press and severe repression, prevented casualties from being appropriately counted and recorded.

On the other hand, we’re left to wonder if the final count has any relevance, considering the unacceptable death pattern, regardless of whether the pattern caused a thousand, ten or even only one victim. The Venezuelan Constitution doesn’t allow the suspension of guarantees that protect the right to Life and yet, there’s a persistent sensation that the suspension of some guarantees was taken by the various security forces as a licence to kill. A captain was recorded by a news outlet saying: “Soldiers have been killed here and when that happens, we intensify our work… [killing] isn’t hard, because we’re already indoctrinated, accustomed and psychologically prepared.”

The people's reactions, the confrontations with the police, the human rights abuses and the confusing narratives around El Caracazo continue to be a dividing topic in today's Venezuela, in particular to those who see the current political and economic crisis as connected to the days that followed February 27.

Gianmarco Greci, writing in his part of the series “Confronting El Caracazo,” argued that it's such a painful and confusing part of the country's history that one must either try to understand it or just not think about it at all:

The responses break down into two overarching narratives: on the one hand the estallido social [a social explosion] narrative of a shortsighted people who did not understand much needed reforms and opted instead for savage chaos. On the other, the despertar de un pueblo [a people's awakening] narrative which politicizes the events as inchoate Chavismo, the awareness-creating moment of a massive political movement against imperialist neoliberalism. Two readings, two Venezuelas.