This is the second installment in “Sleeping or Dead”, a six-part series by activist Sarmad Al Jilane about his experiences in a Syrian prison. Read Part One here.

As I exit I catch sight of a white bus, an image that has been engraved in our memories over the past few months of white regime busses filled with security personnel. I get on board, the only one of all the detainees, along with the driver and the “companionship” as they’re called, a band of five security agents in full military kit. The trip lasted around 80 kicks, 100 lashes—with what I believe was a bicycle tire—and one hour of unconsciousness. Then we arrived at our destination.

They welcomed me with the same rituals at the military investigation branch in Deir-ez Zour. Dozens of detainees in the yard. We all go through a long, wide corridor, and spread ourselves along its two walls, surrounded by around 30 security personnel. The guards assigned to accompany us took any precious belongings we had, such as money, to the small room at the entrance of the corridor.

“Undress.” The order came from a higher-ranking officer. We started taking our clothes off. The blue jacket—I have to guard it with my life. I have to; it belongs to my brother Aghyad who wanted to wear it that day but couldn’t find either it, or me. This thought was the straw I clutched at: the hope that I would get out for the sake of my brother and his jacket. My brother is quite religious; he prays all the time, I am sure God will answer his prayers. We stripped down to our underwear. “These fuckers seem to be visiting us for the first time. Remove your underwear and perform two safety measures: jump and squat quickly. I don’t have the whole day for you.”

I wasn’t going to strip down, for what was being stripped off were the rags of humanity. For 40 years this was exactly what had frightened our grandfathers, fathers and now us. There was no reason for you to jail us, to put us through this much humiliation. What kind of a homeland is it—one that we both share—that rewards us with the likes of you? What kind of a homeland offers your sect a golden shield that protects you from having to strip down completely? Maybe some concepts need to be redefined.

In this moment homeland doesn’t mean home, bur rather a patch of land where people met and were forced to live together. We were forced to live, together, us and them, or die, alone. Power belongs to the person who has the authority over this land. Glory belongs to those who are barefoot and naked, carrying their homelands in their hearts. The tape recording of the constant condemnation of the Americans’ violations in Abu Ghraib prison passes through my head. The president of the one who yelled at us condemned those actions. How ugly must you be to be able to condemn Abu Ghraib, but not even to try to listen to the shouts outside your palace. He may not know it it, but he’s the one who’s stripped down, not us: a free man’s dignity can never be taken away.

Against a chorus of taunts and insults we put our clothes back on and they start assigning us to our cells. “Sarmad to the second group cell.” I enter the cell; there’s silence as the other occupants check out the newcomer. I hang the Blue Jacket in the corner on a metal hook where others have hung their clothes. It’s not important to get to know everyone, as long as the jacket is safe. I sit next to the door, where newcomers usually sit. Everyone’s cautious. “I want some water,” I say, with a burdened sigh. I haven’t drunk water or eaten anything for a day and night. “Here, brother. Move inside, brother, don’t stay beside the door.”. A tired voice like mine comforted my soul before the water comforted my body. Exhausted, I fell asleep sitting upright, and when I woke up it was already night, or at least that’s what I assumed with no sunlight or moonlight by which to measure time.

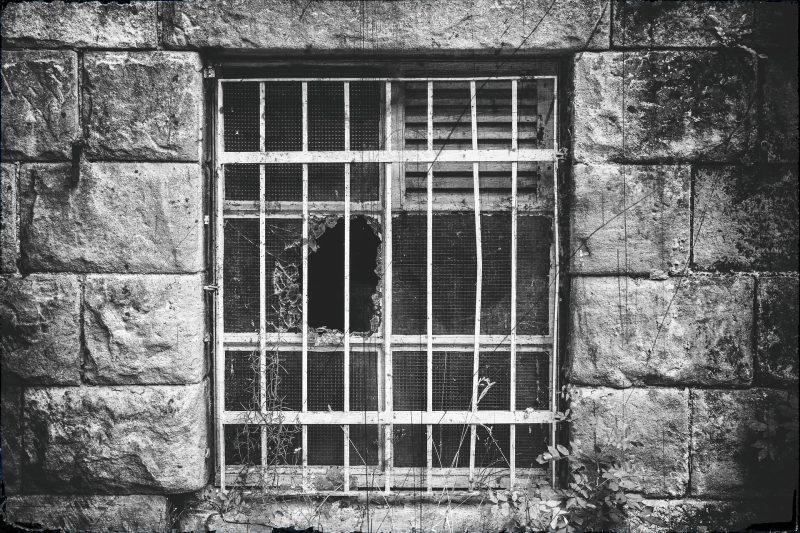

Alone in the corner, despite the number of people crammed into the cell. How many homelands can imprison your body? Or tries to capture as many people as possible. On all-fours, you cry out like a child separated from his mother, but she lets you down! I touch the wall, rubbing it with my hands thinking it must have been made with clay and blood. How many homelands buried this 18-year-old? Shoveled dirt on top of him, stifled him and walked away, as if I never existed.

Maybe they don’t want to imprison us, but are trying to create a homeland for every individual who called for freedom. Maybe they’ve gathered us together here to divide us into smaller homelands, so we keep spinning around with our heads down, and we tell our children stories about a head that looked up and was cut off.

The silence is interrupted when a 40-year-old man starts pressing his palms against the wall. He does it smoothly, with his palms and not his fists, as we do to communicate. A guy answers my inquisitive look. “He is performing tayammum as there is no water here except in the toilet. We drink it and use it for ablution sometimes, but Uncle here prefers to perform tayammum before each time he prays.” He stands in the corner of the cell, with others, praying and reciting Quran in a low voice. I always try to avoid explaining the size of these cells. They are too small to be described, however at times they’ve felt bigger than our neighborhood mosque. “Amen.” The word conveyed a spirituality that overwhelmed me more than my first visit to a church.

“God, my brother Aghyad prays all the time. God, I’m not asking for my own sake, but for his Blue Jacket. It won’t be nice if something bad happens to it and causes Aghyad great disappointment. What about my father? What happened to him? He also prays and calls God a lot—no chance that he is not released yet!” A monologue with myself, after which I slept.

It was six in the morning, as the guard shouted as he entered. “Everybody stand, faces against the wall.” After the roll call he yelled: “Abdul Rahman, Sarmad, Adnan and Ahmed, come forward.” I learned later that they had arrived at dawn while I was asleep. We stepped inside a small, bare room. A table and a chair next to the door, several handcuffs at the back, with a metal pipe in place of a curtain rod, from which hangs a metal chain. A First Lieutenant is seated behind the table, wearing a blue uniform, similar to the navy’s. The executioner was Mohammed AlHalabi, from what the First Lieutenant called him. He unmasked us, and started with Adnan and Ahmed. Both are charged with hunting with an unlicensed weapon: 20 lashes each were enough to recuse them from the investigation room after covering their heads. I and Abdul Rahman remained.

“Today, I am in no mood to interrogate you both, neither will I be tomorrow. We will honor our guests for three days, then we talk.” He left the room. “Undress. Keep your underwear on,” said Mohammed AlHalabi as he approached us.

He holds our hands and puts them in handcuffs, then ties the handcuffs to the chain hanging from the rod. He pulls the chain till we are hanging by our hands, toes barely touching the ground. You’re mid-way between sky and earth, presented as a sacrifice of blood. He covers our heads, and we hear his footsteps as he walks away.

He left quietly and closed the door. We remained silent in fear of provoking his actions. Two hands raised to God, by force. A trickle of blood where the cuffs slice into our wrists. Two feet stretched, trying to touch the floor but with little control. A continuous whine escapes me, and I’m not able to stop it. Abdul Rahman also whines. This was our first introduction to one another, two criminals born and raised on this soil. Two criminals who could not stand to see their homeland suspended, as they are now, who had a staggering self-possession, at a time when humanity was wiped from the dictionary in that deluge of blood in that basement. No occupier will ever prevail. They wouldn’t have done this to us if they weren’t afraid. And now they hang two victorious hearts amid defeats.

The whining slowly increases. “Try to put your feet on mine, to rest a bit,” said Abdul Rahman, with difficulty. I stood on his feet. There’s no way for us to measure how long we are here, we can only estimate it, and we can’t keep this up for long, for fear of a sudden entrance by our tormentor. We switch roles, with him standing on my feet, but it doesn’t really help ease the pain. “This is called Shabeh [a Syrian slang term meaning to hang by the hands or legs], so now when we are released we can tell our friends that we became political prisoners and were subjected to Shabeh,” said Abdul Rahman, failing to hide the pain in his voice.

We laugh at our pain. Time barely passes before both of us are barely conscious. We wake up to the sound of the door being violently opened. It is Mohammed.