The reception area of the Trident Hotel in Port Antonio, Jamaica, displaying one of Stanley's paintings. This particular hotel owns 22 pieces of Stanley's work. Photo courtesy the artist, used with his permission.

British-born, Jamaica-based artist Mike Stanley, whose major one-man exhibit, ‘Passion for Paint’ closed this week at the Mona campus of the University of the West Indies, talked to Global Voices about his early influences in London, his move to Jamaica in the late 1980s — and the tropical environment that has impacted his work in Jamaica.

Global Voices (GV): You prefer to call yourself a “painter” rather than an “artist.” Why and how do you make this distinction?

Mike Stanley (MS): I have been a practicing painter since I was a student at Chelsea College of Arts in London (1963 – 67). It’s always been what I do. When people ask me what I do, I tell them I’m a painter. There was the explosion of ‘abstract expressionism’ in New York in the late 1950s, when European artists moved to the United States after World War II. Jackson Pollock was a great abstract expressionist painter. Then there was ‘post-painterly abstraction’, which involved greater use of color. In 1960s London, we had a ‘European take’ on that style. This is how my style developed, through the influence of these artists; my style has always retained the notion of paint as a language. These days, though, paint is regarded as ‘old hat’.

GV: Tell us about your artistic life in London. How did you get started?

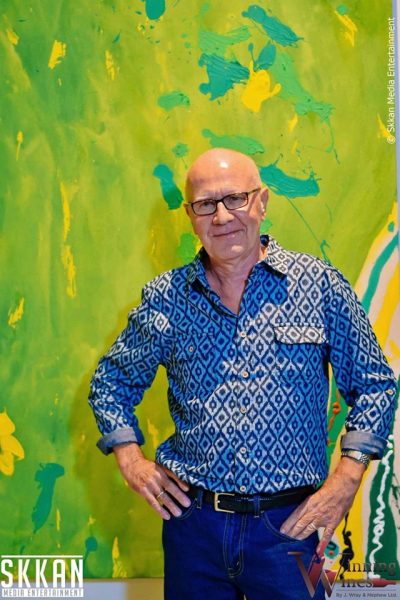

Painter Mike Stanley at his recent exhibition at The University of the West Indies Regional Headquarters — a wonderful space for art. Photo courtesy the artist, used with his permission.

MS: I started exhibiting while I was still a student at Chelsea. I won second prize in a student exhibition in 1966 called ‘Young Contemporaries’. I won 50 Pounds. I spent my prize money on driving lessons. I continued to paint throughout the '70s and '80s, supporting myself by teaching. I have never been a ‘dyed in the wool’ teacher, but I have to give thanks for the income, which allowed me to keep painting. I always say the best thing about teaching is the students.

During that period, painting became a kind of subversive activity. There was little support from the art establishment in London; the art gallery scene was all to do with ideas — conceptual art. Some art schools even stopped teaching the traditional skills of painting, drawing and sculpture. I went my own way. It was not easy being an artist in London — and there were many of us, exhibiting in warehouses and the like. We were ‘family’ — one big family of people who used paint.

GV: Who was your greatest influence in England? Who inspired you to continue painting?

MS: I had a great teacher, John Hoyland, from my first year at Chelsea onwards. He was a part of the art establishment and had quite a high profile career. His teaching wasn’t at all formal; he taught through telling stories. He was also very funny — we used to bust up with laughter, even to the point of tears. Although his paintings were great, what I really learned from him was an attitude.

GV: So what was behind your move to Jamaica?

MS: I came to Jamaica in 1988 with my second wife Margaret, who is a Jamaican textile artist, and our two year-old daughter Suzi. Margaret had always kept in touch with her Jamaican family, and we had paid several long visits. At the time, we were both teaching in the UK; it was our bread and butter. Then we were both made redundant by Maggie Thatcher! We arrived in Jamaica with the idea of trying it out for a couple of years. I was drawn to Kingston, because you aren’t seen as a tourist here, you can be yourself — 28 years later, we are still here.

GV: Did you adjust easily to life in Jamaica?

MS: Well, it wasn’t easy making a living, teaching and painting in Jamaica. So I used to supplement my income by traveling to the UK to do supply teaching, every summer. I did this for more than ten years; it kept us going.

GV: Your paintings are bright and colorful. What does color mean to you?

MS: Well, you know, this annual trip, from Jamaica to the UK, made me recognize the huge difference in the light. The way you see color changes. As you fly into the UK, the colors are muted. The light changes completely. It’s more natural to me to be colorful in my work. I always embraced color; I used to call myself the ‘Gauguin of West Norwood'! Many European artists’ work became more colorful when they moved south — for example, Delacroix, Van Gogh. The environment affects you.

GV: As artists, how have you and your wife Margaret influenced each other?

MS: Margaret’s work has always been a big influence on me. She has always channelled tropical imagery and color in her work. I would say her influence has increased over the years. Now — especially in my latest exhibition — I am leaning more towards semi-figurative art, myself.

GV: Now, here in Jamaica, what do you enjoy the most about your art?

MS: I am doing more big paintings again. I hadn’t done any big paintings for some time. But when I saw the Matisse exhibit at the Tate Modern in 2014, there were these huge cutout pictures. I thought, ‘I’ve got to do more big paintings’. By the way, you can see many of my large-scale works at the Trident Hotel in Port Antonio; they bought 22 of my paintings. Perhaps my early work at an architecture office in London inspired my large pieces — I am interested in public spaces. Now, funnily enough, I am teaching art at the Caribbean School of Architecture at the University of Technology in Kingston. Back to where I started!

Since I have been living here, I have exhibited on average every two years. I have had three large one-man exhibitions, roughly every ten years, with smaller ones in between and some joint exhibitions with Margaret.

GV: Finally, what are your thoughts on the current state of the Jamaican art scene?

MS: When we first arrived here, the art seemed like watered-down versions of what we had seen elsewhere. This was because many were trained outside Jamaica. Then David Boxer brought the (self-taught) Intuitives to public attention at the National Gallery of Jamaica — something so unique to Jamaica, something I’d never seen before. Younger Jamaican artists nowadays have more ambition, more professionalism. They have a more international approach, but they still retain a very Jamaican ‘twist’ — like Matthew McCarthy, who used to paint signs; and Leasho Johnson, a painter and graphic artist. The National Gallery of Jamaica has taken a more international approach in recent years, representing many different strands of contemporary art.