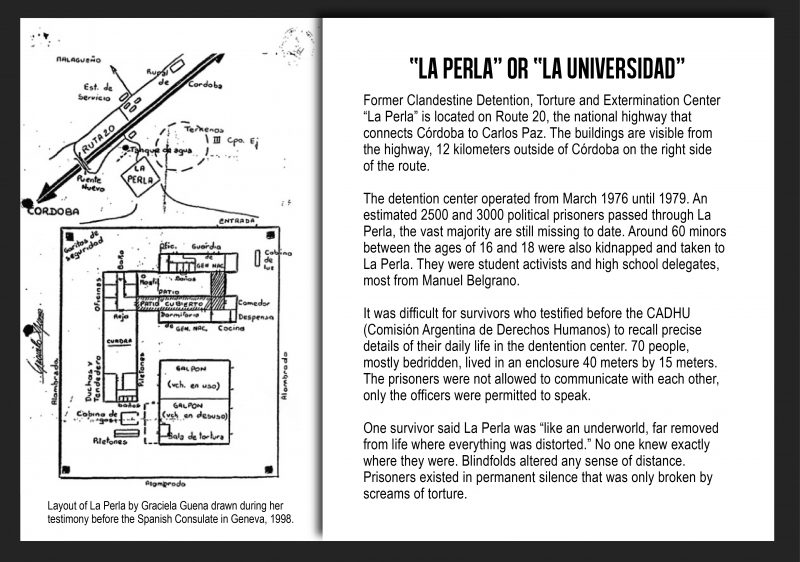

Luis Quijano. Photo: Nicolás Bravo. Used with permission.

This is an adapted version of an interview with Luis Quijano by Alejo Gómez that originally appeared on August 23, 2016 in Día a Día [1]. It was translated [2] and published here with permission.

When he was 15 years old, Luis Alberto Quijano’s father forced him to witness the horrors of La Perla, a clandestine detention center in the city of Córdoba [3], Argentina. Now an adult, Luis testified against his father in the La Perla-Ribera mega trial [4] in the province of Córdoba for crimes committed during the dictatorship. Forty-three oppressors were charged with crimes against humanity in the trial, which concluded on August 24, 2016.

Luis Alberto Quijano didn’t choose his life. From the burden of having the same name as his father, to being exposed to brutal military operations in La Perla when he was 15, he had suffered long enough. He kept the family secret for 34 years.

En el contexto de esa época yo creía que estaba bien. Me sentía un agente secreto. Pero a los 15 años, un hijo no puede darse cuenta de que es manipulado por su padre. Yo no estaba preparado todavía para darme cuenta de que mi padre era un ladrón, un torturador y un asesino.

At the time, in that context I thought it was okay. I felt like a secret agent. But at the age of 15, a child doesn’t realize that he’s being manipulated by his father. I was not prepared yet to understand that my father was a thief, a torturer and a murderer.

Luis had no choice: his father was Gendarmerie Officer Luis Alberto Quijano, second in command of the Intelligence Detachment 141 at La Perla from 1976 to 1978, during the Argentine military dictatorship [5], a period of state terrorism [6] in Argentina from roughly 1974 to 1983.

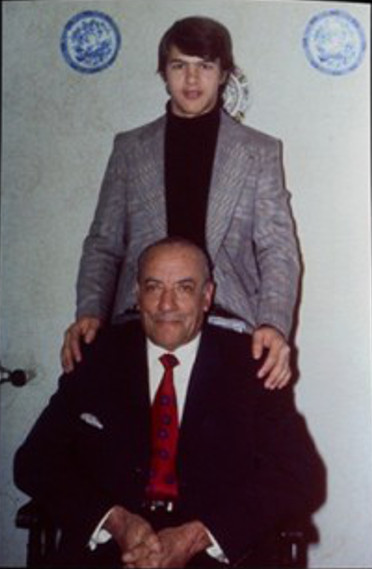

Luis Alberto Quijano. Archive photo.

This isn’t the story of Luis Quijano the oppressor, accused of 158 kidnappings, torture, almost 100 homicides and the abduction of a 10-year-old child. It is the story of Luis Quijano’s son, a man who over the years learned the magnitude of the terror he had lived as boy and ultimately testified against his own father in federal court.

It is a story that reflects the immense power that a parent has over a child, and how that child can choose a path of redemption.

From the gym to the Detachment

When my father started taking me to the Detachment, I had been going to the provincial gym and became friends with a boy who did martial arts. They called him “Kent.” I told my father and a few days later he showed me a black-and-white photo card and asked me to identify my friend.

He said:

Me dijo “sos un pelotudo, ¡te hiciste amigo de un tipo del ERP! Mirá si después te ‘chupan’ a vos y me tengo que entregar para salvarte.

You’re an asshole, you made friends with an ERP! Watch, later they’ll kidnap you and I’ll have to save you.

The ERP stands for the People's Revolutionary Army, [7] which was the military branch of the communist Workers’ Revolutionary Party in Argentina.

So he forbid me to go back to the gym, and a few days later he took me to the Detachment to work. He told me I was going to be a secret agent. I was 15, and in that context I believed it was okay because it was what my father had taught me.

At the Detachment, they made me destroy documentation that belonged to the prisoners. Documents of all kinds: university degrees, handwritten notes, literature, certificates, propaganda, books, everything.

Photo: Comisión Provincial de la Memoria [8]

‘Over there is where they torture the prisoners’

My father took me to La Perla four times, all in 1976. The first and fourth visits, he left me waiting in the car at the entrance.

The second time he made me get out and he took me to a shed where there were cars, furniture, televisions, refrigerators, anything you could imagine. All of it stolen. He gave me a package wrapped in a blanket and told me to take it to his car, and when I opened it, I saw it was a giant lump of silver.

That day I went to the other side of the shed where they dropped off the stolen things and I started chatting with a gendarme who was standing guard. At one point he gestured to an open room and told me:

ahí es donde les dan ‘matraca’ a los secuestrados.

Over there is where they torture the prisoners.

I peeked in and saw a bed where they tortured people. It was like a military cot with metal springs. Later I learned that they hooked up a stripped negative cable to the metal and used another positive cable to touch the body of whomever was tied down. They would handcuff a person on the cot, drench them with water and apply 220 volts to their genitals.

Photo: Comisión Provincial de la Memoria [8]

There was such an appalling odor in there… like a dirty diaper. Years later, when my father was being held under house arrest, the same smell emanated from his room. I made the connection and realized that it’s the smell of a body in distress. I could never forget that smell. And I wondered, how is it possible someone could do so much damage to another human being?

‘I had full knowledge that they killed those people’

The third time my father brought me along to his work, he took me to the entrance of La Cuadra (the area where prisoners were handcuffed and blindfolded). He was talking to “Chubi” Lopez (Jose López, a civilian prosecuted in the trial) and I took advantage of the opportunity and looked inside La Cuadra.

In the back I saw a row of mattresses with naked people lying face down, all were tied at the hands and feet. Closer to the entrance, there were other people sitting silently squatting on mattresses. My father saw that I was looking at the prisoners and said: “What you looking at, asshole?” And I said, “Well, why did you bring me here?”

I had full knowledge that they killed those people. They threw them in a pit and military personnel shot them and buried them. I know because my father talked about it at home.

Next to La Cuadra there were some rooms they called offices. I know that “Palito” Romero beat someone badly there and killed him. (According to survivors, civilian Jorge Romero, who was indicted in the La Perla-Ribera trial, beat student Raúl Mateo Molina [9] to death).

In the video below, Emilio Fessia, director of the Space for the Memory at La Perla, gives a tour of the former torture site.

El camino por el cual ustedes vienieron y la ruta, era el camino por el cual entraban las personas secuestradas. Y más o menos, si ven el plano, hacían este recorrido y aquí los bajaban para su primera sesión de tortura. […] Era donde se les cambiaba el nombre a las personas y se les ponía un número en este proceso de deshumanización. […] Y si sobrevivían las sesiones de tortura, venían las personas detenidas desaparecidas y eran tiradas en la cuadra hasta que venía la orden de los superiores para trasladarlas. Que es la mentira, el eufemismo que utilizaban para fusilarlas y desaparecerlas en la gran mayoría de los casos.

The road in which you came in and the route was the one in which the kidnapped people entered. If you look at the map, more or less they took this path and were taken to their first torture session. […] Here's where their names were changed and a number was assigned as part of the dehumanization process. […] If they survived the torture sessions, the disappeared detainees were thrown in the cuadra until an order came from the higher officers that they should be moved. This was the lie, the euphemism they used for shooting and disappearing their bodies in most cases.

The ‘spoils of war’

My father brought home all kinds of stolen goods. But, at that age, I had no idea what was meant by “spoils of war,” as they called it. But later when I was in the military (I was in the gendarmerie), I realized spoils of war would be a bayonet or maybe a military patch that you took from some enemy you had fought.

Luis Alberto Quijano and son. Archive photo

But if you walk into a house and steal the refrigerator, the record-player, clothing, paintings, money…those aren’t spoils of war, it’s vandalism. That is theft.

I always wondered how my father, the chief officer of a security force, could participate in such vandalism. I don’t understand it. I was also an officer in the gendarmerie and it never occurred to me to enter a house and steal everything.

I do not understand how my father did that. Once he told me that I was a criminal, and I replied: And you, who steals cars off the street? You’re not a criminal? He exploded in a fit of rage, hit me and yelled:

¡el día que te cruces de vereda, ese día te voy a buscar y te voy a matar yo. No hará falta que te mate otro!

The day you cross that line, on that day I’ll find you and I’ll kill you myself. No need for someone else to do it!

That was my father. I have no good memories of him.

When I testified in the trial, I showed a photograph from back then where I was wearing a jacket and a wool turtleneck my father had taken from La Perla. We were not poor, but he brought home clothes just the same. At the time, the defense accused me of being a co-conspirator in those crimes, and I said no problem, they could accuse me of whatever they wanted.

I was there to testify anyway.

‘To disappear the body is the final, odious act’

Now that I’m older I feel remorseful. I have children; once you have children you realize the value of a life. You evolve and understand that killing is wrong. I even went so far as to say:

Incluso llego al extremo de decir ‘bueno, suponé que fusilabas durante la dictadura”, pero ¿por qué desaparecías los cadáveres? ¿Por qué robabas niños?

Fine, suppose you executed people during the dictatorship, but why disappear the bodies? Why did you steal children?

My father had once brought home a girl whose mother they killed. It was like a pet: almost like a dog, only it was a little girl. Those thoughts kept going through my head: They were tortured, but why were they killed? They could have just put them in jail. I guess they decided to kill them, but why disappear the bodies? Didn’t those people have families to claim their remains? To disappear the body is the final odious act to do to a human being.

My father told me that when democracy returned they brought in machines to remove the remains, they ground them up and dumped them, I don’t know where. “They’re never going to find anything,” my father said. But of course something always remains.

‘I’ve seen you kill people!’

Just to clarify, I have nothing against the armed forces. In fact, I was a member of the gendarmerie. All I did was tell the truth about 20 criminals, including my father.

The complaint against my father developed while talking to him when he was under house arrest. I reproached him for making me live through such atrocities. At one point he said: “I don’t know, I didn’t kill anyone.”

I felt repulsed inside, I wondered what all that jingoism and all that “Western and Christian sentiment” that they claimed to be defending was for.

Then I shouted:

Entonces le grité “¿cómo me vas a decir eso a mí? ¡Si yo te he visto matar gente! Cometiste delitos muy graves y me hiciste participar en esos delitos siendo yo un niño.

How can you say that to me? I’ve seen you kill people! You committed very serious crimes, you made me participate in those crimes as a child.

And he said, “Well, go denounce me then.“

And so I did. In 2010 I filed the first complaint. I finally realized he was a criminal.

No one can tell me I’m biased, I testified against my own father.

Luis Alberto Quijano died in May 2015 [10] while under house arrest before the trial concluded.

He was charged with 416 offenses: 158 counts of aggravated unlawful deprivation of liberty, 154 counts of torture, 98 counts aggravated homicide, five counts of torture resulting in death and the abduction of a child under 10 years of age.

Photo: Luis Alberto Quijano. Archive photo

The ‘megacausa’ verdicts

The word “megacausa” in Spanish refers to the scope of this judgement. After four years of hearings including over 581 witnesses, the historic La Perla-Ribera mega trial for crimes committed against 716 victims between March 1975 and December 1978 finally came to an end in August.

Forty-three oppressors were found guilty of crimes against humanity, and the court handed down 28 life sentences, nine sentences of between two and 14 years, and six acquittals. Eleven of the original 54 people charged died during the trial.

#SentenciaLaPerla [11]: asesinatos, tormentos y violaciones cometidos por funcionarios públicos.#FueTerrorismoDeEstado [12]pic.twitter.com/onmD7cEuJb [13]

— Abuelas Plaza Mayo (@abuelasdifusion) August 25, 2016 [14]

#LaPerlaSentence: murders, torture and rapes committed by public officials. #ItWasStateTerrorism

All were members of the armed forces during the dictatorship, including ex-military, ex-police and some civilian personnel.

Piero De Monti, who was kidnapped along with his pregnant wife in June 1976, both were taken to La Perla. He spoke to the silent chamber:

La Perla fue una fábrica de muerte concebida por una mente antihumana

La Perla was a death factory conceived by an inhuman mind.

The ruling marks a historic milestone for the human rights organizations who worked for years to get justice for the victims. Claudio Orosz, attorney for H.I.J.O.S. [15], an Argentine organization founded in 1995 to represent the children of persons who had been murdered or disappeared by the dictatorship, said:

Fueron más de tres años de juicio pero 39 años de investigación

The trial was more than three years, but 39 years of research.

In March 2007, the national government turned over the land on which La Perla was located in order to establish a memorial [16], which is now managed by human rights organizations.