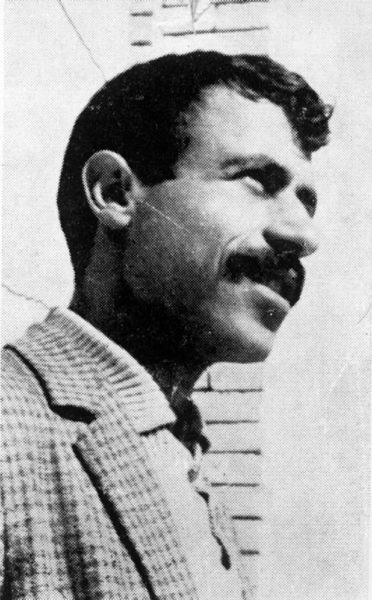

Samad Behrangi, born June 24, 1939, and died August 31, 1967. Photo: Alchetron Encyclopedia.

August 31 marks the 49th anniversary of the passing of the Iranian-Azeri author Samad Behrangi. Even now, almost half a century after his death, Behrangi’s words and ideas are cited by political prisoners and Iranian activists who continue to fight censorship, poverty, and injustice in their homeland. Though his life was short, Behrangi’s legacy still inspires writers today from all different backgrounds.

Behrangi was born in the northern city of Tabriz to an Azeri Turk family (one of the largest minority groups in Iran). Behrangi became a teacher at the age of 18, and begun his work teaching in the rural villages of Iranian Azerbaijan. The terrible conditions in these schools and the lack of resources for his students not only radicalized Behrangi, but also provided him with a source of passion going forward.

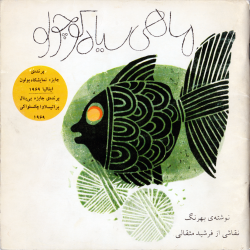

Behangri is perhaps best known for his short story, Mahi Siayeh Kochooloo, or The Little Black Fish, which follows the journey of a small fish from a small stream to the vast ocean. The story reads as a children's tale, but explores the intersection between coming of age, and the development of political and social consciousness. The protagonist of the story is faced with an ongoing desire to explore life outside of the simple stream, and find out if another life is actually possible. The Shah of Iran would later ban the story.

The original book cover for Little Black Fish published in 1967. The illustrations by Farshid Mesghali won several awards including the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 1974. Image: Wikipedia.

Dissatisfied with the materials provided in the rural schools, Behrangi tried to make his own teaching materials, aiming to create something that better reflected the reality familiar to the rural children. The government of the Shah prohibited the publication of such materials. Throughout his life, Behrangi would face suspensions and threats as a teacher because of his political ideas.

Preferring to write in Azeri, Behrangi wrote critical essays about Iran’s education system, folk tales, short stories, and translated the works of Iranian poets and writers. Behrangi also attempted to collect and write down a series of Azeri folk tales and children's stories, but was again denied publishing rights in his native tongue.

Behrangi was a Marxist, a passionate instructor, a social critic, an imaginative writer, and above all a thinker who grappled with what was at hand. This included a decadent monarchy that espoused modernization but did little to alleviate the ills of Iran’s lower classes. This growing discontent began to spread among society's educated classes, including those young Iranians like Behrangi who embraced radical change.

One of his best-known books (and my own personal favorite) is Kachale Kaftarbaz, or “Baldy the Pigeon Keeper” (retold orally in the video below). The tale revolves around Kachal (Baldy) and his struggle against a tyrannical king. The protagonist, who is bald, poor, and aloof, does not pursue wealth or power. Kachal takes a courageous stand against the violent oppression of the king, while maintaining his simple and honest life. In a hilarious twist, he also uses his pigeons to drop goat droppings on the heads of the king’s soldiers—a humorous yet subtle homage to the legitimacy of armed struggle against dictatorship.

This story, like many of Behrangi’s tales, contains both humor and sombre examinations of society, including subtle commentary on inequality, land use, and women’s rights. His writing is also unique in that it maintains a classical folklore style, while subverting the escapism that is typical in that genre, and instead focuses on social justice as the moral of the story, even above personal happiness and security.

Behrangi’s writing style is reminiscent of Miguel de Cervantes, in his ability to meld absurd and fantastical elements with a subtle critique of society and the status quo. Like Cervantes, Behrangi used humor and irony in his seemingly harmless stories to present a subtle yet sharp critique of life under the Shah of Iran. Using words, Behrangi hoped to arm those who were most affected by poverty and inequality in Iran.

Behrangi stands out not only for his political thoughts and imaginative ideas, but for the distinct manner and style of his writing, which was made accessible for the masses. His ideas and vocabulary were presented in such a manner as to reflect common speech. His stories centered on the harsh reality of life in an unequal world. They were meant first and foremost to provide guidance and awareness to young children, and direction in overcoming the ills that they faced.

Behrangi sought to break with the standard narrative offered in children's books, and instead provide guidance as a means towards societal change:

It is no longer the time for limiting children's literature to the arid and authoritarian advice and instructions, such as ‘Wash your hands and feet and body’, ‘Obey Mum and Dad and the elders'… Shouldn't we tell the child that in your country there are boys and girls who have never seen a piece of meat on their plates? Shouldn't we tell the child that more than half of the world's population are hungry, and why they are hungry, and how hunger could be diminished?

What cemented Behrangi’s status among Iran’s mythical figures during the lead up to the 1979 revolution was his sudden and mysterious death. Reports indicate that Behrangi drowned in the Aras river on August 31, 1967. At the time, many believed his death was no accident, and a common theory holds that his murder was organized by the Shah’s secret police, the SAVAK. Others have stated that his drowning was simply an accident.

His unnatural death and his political ideals elevated his status to that of a martyr, joining other notable activists and thinkers who died under mysterious circumstances in the same era, including Ali Shariati, Gholamreza Takhti, and Forough Farrokhzad. His face would become a symbol of resistance to the regime and his writings would both incite and instruct a generation.

Iranian protesters hold a portrait of Samad Behrangi. Date unknown. Photo: Alchetron Encyclopedia.

Within a decade of his death, young Iranians would organize and spearhead a nationwide movement against the Shah in what became known as the most “popular revolution” in modern times. This included a strong leftist element, which took inspiration from Behrangi, among other prominent intellectuals and thinkers.

Behrangi’s words and message are as rich and powerful today as ever. On the anniversary of his death, we can once again ponder the lines he left us in the Little Black Fish:

I might face death any minute now! But I should try not to put myself in harms’ way as long as I can live. Of course it is not important if I die, because this is going to happen anyway. I know my purpose, my purpose is: How will my life or death impact the lives of others?

1 comment