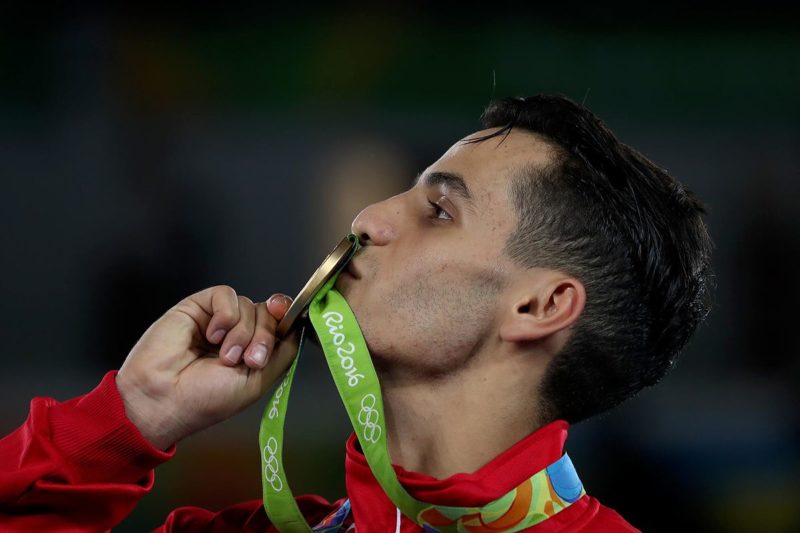

[1]

[1]Ahmad Abughaush kisses the gold medal he won for Jordan in the 2016 Olympics in RioTaekwondo PHOTO: Salem Khamis (CC BY-SA 4.0) via Wikimedia Commons

By Huda Ziade

When taekwondo athlete Ahmad Abughaush [2] clinched the first ever gold medal for Jordan in the recently concluded Olympics in Rio, Jordanians, Arabs, and the world [3] erupted in joy to celebrate the accomplishment and his brilliant performance. But or many Jordanian-Palestinians like myself, the initial burst of joy was followed by a bitter-sweet aftertaste. Most of us didn’t know Abughaush before his win, but for Arabs, it didn't take more than his last name [4] for us to know his story. After all, it’s on our last names that we are constantly being judged.

As Jordanian and global media shared the news of Abughaush’s win, they neglected to mention his Palestinian roots or the fact that he was the son of Palestinian refugees. I felt this was an active erasure of Abugaush’s Palestinian identity, but the full impact didn’t really hit me till I saw how Israeli media [5] reported it. “His family decamped for Jordan shortly after the birth, but a number of relatives still live in the picturesque town, famed for its hummus restaurants.”

“Decamped.”

The reality is that the Abugaush family were forcefully expelled from their village on two occasions: first, when they destroyed Saeed Abugaush’s homestead in April 1948; and then again, when the Abugaush family fled, along with thousands of other Palestinian families, in the aftermath of the Deir Yassin Massacre [6], what Palestinians now call now the Nakbeh [7] (“Catastrophe”). In the years after the Nakbeh, as many members of the Abugaush family tried to return to their hometown, they were killed by the Israeli army as “infiltrators”.

[8]

[8]Palestinian refugees leaving Galilee during the period of the Nakba in 1948. PHOTO: Public Domain.

In Jordan, the context is slightly different, but the erasure is the same. The Nakbeh in 1948 forced many Palestinians to move to Jordan, as well as the West Bank, which was annexed by Jordan after the war. This was when many Palestinians were naturalised and given Jordanian citizenship. After Israel occupied the West Bank in 1967, another wave of Palestinians was forced further into Jordan.

In July 1988, Jordan unilaterally surrendered its claim to the West Bank [9], a decision which opened the door for the Palestinian Liberation Organisation to become the sole representative of the Palestinian people. For Jordanian-Palestinians, it meant that we could become stateless people overnight.

The mandatory visits to the Jordanian Department of Followup and Inspection became a nightmare for Palestinians living in the country. The Department was established under the Ministry of Interior and tasked with categorising West Bank citizens as separate from Jordanian citizens. How it did so was opaque, and split many families apart. Thousands of Jordanian citizens were stripped of their national identification numbers and were issued temporary passports instead.

[10]

[10]Identification Card of Ahmad Said, a Palestinian refugee. PHOTO: mickyx09 (CC BY 2.0) via Wikimedia Commons

So while many of us Jordanian-Palestinians love the country where we grew up, Jordan doesn’t necessarily love us back. We navigate this complex identity as if we are walking on hot coals, getting burned whatever direction we take.

Being Palestinian in Jordan is about facing systematic discrimination. It’s knowing that while your accomplishments belong to the collective, your failings are your own. As a Palestinian, you do not truly belong; but you have nowhere else to go because you are Jordanian. You are an incomplete citizen and a permanent refugee. As people celebrate Scottish football fans carrying Palestinian flags in a stadium [11], we Jordanian-Palestinians are prohibited from carrying Palestinian flags in the open in the country where we live. We celebrate our national identity in private and are excluded when other Jordanians celebrate theirs—which should also be ours.

But we don’t know any other way but to be who we are. Being Palestinian is about remembering the place we came from, the place to which we are not allowed to return. Being Jordanian for us is about where the place where we’ve grown up, our friends and family, and the life we’ve built together here.

So forgive me if I feel a bit incredulous towards the nationalistic adulation showered on Ahmad Abughaush, particularly when it comes from the same people that who make fun of Gulf Olympic teams from the Gulf for “buying [12]” athletes from other countries to compete for them. After all, as fans of the Wehdat refugee camp football club know [13], our Palestinian identity, and the fact that we are naturalised and not native Jordanians, is always used against us, and constantly pitted against an incomplete, exclusionary version of Jordanian identity. It must be convenient to be able to erase and rearrange the identities of people as you wish.

People like me know that being Jordanian and being Palestinian are not incompatible, because we are in fact both. Either by choice or because of external forces, we were part of this country from the start, working hard, like all Jordanians, to build it into what it is today. We believe in a Jordanian identity that includes us and empowers our struggle for national liberation, not one that erases us. It’s unfair that we should have to hide our Palestinian identify to serve an agenda that excludes us.

When Jordanian-Palestinians succeed, we want to be able to celebrate our whole identity, and most importantly, our story. That starts by celebrating Ahmad Abughaush, the Jordanian-Palestinian who fought his way up to the top of the podium.