Wading across the Kizgych River, Teberda Nature Reserve. Photo by Anton Lange. Used with permission.

A region so rich in unique cultures that it could even be called “a country within a country,” home to Russia’s most conservative Islamic communities, and an area where the federal government practices domestic policies like nowhere else, the North Caucasus enjoys a special, albeit controversial, identity throughout Russia and the rest of the world. After being a seat of intense violence between federal armed forces and local separatist movements for more than 15 years (with the last official military operation occurring as recently as in 2009), Chechnya, Ingushetia, and Russia's other Caucasian republics are gradually developing into a new North Caucasus that projects itself outward as prosperous, integrated, and open for visitors.

The new regional policy is marked by a strong federal presence and heavy funding. Chechnya's ruler, Ramzan Kadyrov, is regularly in the news for his ardent and sometimes bizarre expressions of support for Vladimir Putin. In St. Petersburg, critics of Kadyrov's father recently failed to stop the renaming of a bridge after the man, Akhmad Kadyrov.

With these political scandals usually dominating news headlines, RuNet Echo turns its attention a cultural story from the region revolving around a new art project.

Because of the region's bloody history and troubled present, it's sometimes hard to remember that the North Caucasus isn't a land of death and destruction. The area is also a treasure trove of unique cultures and untamed natural riches. The journey requires understanding and preparation, however, and that's where a new art project comes in.

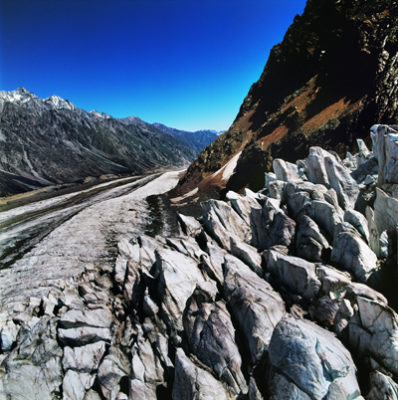

“The Range. The Caucasus from Sea to Sea,” by Anton Lange (one of Russia’s top photographers), launched earlier this summer as a Web project, which was preceded by a major photo album and a number of exhibitions. With his latest work, Lange, who's known best today for “Russia Through a Train Window,” has made a bold new effort to do justice to the region’s breathtaking natural and cultural legacies. A partnership with the Northern Caucasus Resorts JSC enabled the project team to explore the entire length of the Greater Caucasus mountain range and its northern slopes, in a search for original angles and undiscovered landmarks.

Ksenia Khudadyan spoke to Anton Lange about his Caucasian journey, which he says every person should find a way to experience.

Ksenia Khudadyan (KK): The general media coverage forms a rather dubious image of the Caucasus as a region, from the social perspective, first of all, and contributes to the development of certain stereotypes. Evidently, they can't all be true. Probably the most obvious stereotype is that anyone visiting the area is in extraordinary danger. How true was this for the project's team?

Anton Lange (AL): It's true that the region's image is contradictory—and the Caucasus itself is indeed a land of contradictions. It goes without saying that the media automatically exaggerates the level of danger, and it offers scarce, if any, coverage of good news from the Caucasus. But journalists pick up immediately on any problems, of course, broadcasting the news on every channel.

Once a story is online, it's there to stay. So when you look up “the Caucasus” on the Internet, you're showered with a pile—a heap—of news about explosions, shootouts, special operations, and so on. As a result, the picture of the region is quite distorted, and outsiders come away with the impression that the Caucasus is an incredibly dangerous place, but this isn't so.

It would also be untrue to say that the Caucasus isn't dangerous at all. Obviously, the Western Caucasus, which is closer to Sochi and full of resorts (mainly ski resorts like Arkhyz), isn't fraught with any dangers or threats. At the same time, there are places (like certain areas in Dagestan) that are inundated with security forces, where you need special permission just to enter. You can find it all.

The Towers of Two Rivals on a branch of the Skalisty Mountain Range. Photo by Anton Lange. Used with permission.

KK: Until very recent times, the history of the Russian Caucasus has been a story of confrontation between the empire and native peoples, so to speak. Can you tell us about interesting moments in your work on the project when you intentionally toned something down, leaving something off screen? Did you ever feel like you had to “edit the reality”?

AL: I wouldn't say we had to edit the reality. There were stories, however—certain things that we could have emphasized more. I'm talking about both more recent episodes, like the Chechen Wars, and things from the more distant past, like the deportation of entire peoples in Stalin's time, and the tragic events in Kabardino-Balkaria, for instance.

Personally, though, this wasn't something I engaged in; I'm not too involved in politics or history. My interests lie in the region's nature, ethnography, landscapes, and portraits—the artistic, traditional, and classical genres, instruments, and methods of exploring the outside world.

That said, we did include—in both the album and in the exhibition—villages destroyed in 1942 by agents in the NKVD [the KGB predecessor]. It's hard to pass any unambiguous judgment on the situation there.

The first thing to consider is that the Caucasus—the North Caucasus—is unbelievably hospitable. The roots of this hospitality lie in the ancient highland law, the so-called adat. When certain peoples were converted to Islam, they adopted a whimsical combination of adat and Sharia law. Later on, this cultural combination was entangled with Soviet customs and Soviet law. But adat remained the basis of highland ethics and highland law. In fact, [the hospitality required by] adat is the highland law, and highland hospitality is not merely an act of individual goodwill.

Thus, speaking of Dagestan, it's worth noting that there isn't a single hotel in highland Dagestan, and it is the largest republic in the North Caucasus. There are a few in the lowland part of the republic, near the Caspian Sea, but there is none in the mountains. If you are traveling in the mountains, you will definitely be staying at people's homes as a guest. Caucasian hospitality doesn't mean that someone is more hospitable than others, or that someone is willing to welcome a guest while the other is not. This kind of hospitality is a universal obligation to welcome every guest. It is not a matter of discussion; it goes without saying.

As soon as you arrive in an ancient highland village, such as Kubachi or Khunzakh, or any Dagestani settlement, everyone welcomes you with great enthusiasm as a representative of “the big Russia.” Everyone tells you, “A lot of Russians used to come to us, but no one comes now, because they are afraid, and it makes us so frustrated and sad….” And they invite you into their homes, offer a cup of tea or some local treats, and suggest that you stay at their place. No one charges you any money, as it is prohibited by the same highland rule. Anyone who dares take your money invites great shame in the eyes of their fellow villagers.

Paradoxically, there is no concept of tourism in this land; there are only guests. I don't mean touristic destinations such as Arkhyz or the vicinity of Mount Elbrus—I'm talking about places where ancient ways are maintained, such as highland Dagestan, highland Ingushetia, highland Chechnya, or highland Kabardino-Balkaria. It's very difficult to give a definite answer to the question about conflicts…

Chechnya has gone through two terrible wars, preceded by mass deportations during WWII, in 1944. The Chechen people have survived one tragedy after another. The Chechens could be holding a huge grudge against us [Russians], but I have experienced an amazing destruction of stereotypes. It hasn't been even a decade since the debates about Grozny's restoration (the city was in such ruins that city planners even discussed rebuilding the capital in a different spot), and today you can come to Grozny as a welcome, seemingly long-awaited guest.

When you come to the Chechen highlands, you are received in the same way. And the people are sincerely happy to see you, because, again, you are an ambassador of the great country, the big Russia. I am convinced that every single resident of the North Caucasus is bound to feel isolated from the rest of the world, even if it's on a subconscious level. Because of the bias and a variety of other reasons, people from the North Caucasus face a lot of barriers. This is why the Internet is so widespread there and the use of social networks and Instagram is so ubiquitous: they serve as a window to the great outer world. This is why they are so keen on surfing the Net and Instagramming: they are all visionaries. They have to see everything and show it to the world, passing it around to everyone. I'd say it looks even more obsessive than anywhere else around the world.

During my first visits to Chechnya, I kept trying to understand how that terrible war that claimed so many civilians’ lives ended such a short time ago. Historically, it ended only yesterday. I kept trying to understand how we, the Russians, are perceived, almost forcing myself to feel resentment of the locals, or something hidden under a mask. But I couldn't feel any of it. Maybe there was something, but I never felt it.

I asked the people how it is that so much blood was spilled so recently, but that it doesn't feel this way in the region. And most of them answered something like, “You know, the blame was partly ours, too, and our share was pretty big. We just accepted that the hostilities couldn't go on forever, and both consciously and subconsciously we accepted a certain mutual settlement and agreed to a clean slate.”

It seems to me that people in the Caucasus know the price of resentment, betrayal, and blood better than people anywhere else. They know that the price of resentment is immeasurably great, and you need to have enough strength, courage, and wisdom to get over an offense—to step over it—as the price you would have to pay otherwise is a thousand times more. Unsurprisingly, the nations that once had a tradition of blood feud know it a lot better than others. This might even facilitate processes like mutual understanding, mutual forgiveness, or mutual settlement—I can't think of an exact term. Generally, it's a very interesting experience, both psychological and personal, as well as humanistic. One thing for sure: you can't hope to gain a deep insight all at once—it's too complicated a story. It takes a lot of visits.

KK: What's the Caucasus like for a photographer? What makes it special? Would you call it an exotic destination?

AL: The mountains present a huge difficulty for a photographer in general because their beauty is commonplace. It's incredibly difficult to take an interesting mountain photograph. The closer you are to perfection in terms of technical skills, the weather and the chosen routes, the more and more often you face a glossy postcard view. In such situations, my cameraman would pack his lens, saying, “Let's wait for the weather to get worse.” More than any other landscape on the Earth, the mountains offer a range of banalities: rocky cliffs, glaciers, snowy peaks…. Bang your head against them if you like, but it's impossible to figure out what to do with them.

And this is why the mountains challenge not only mountaineers, but photographers, as well: try and find an exciting, original angle, make your pictures different from millions of other mountain photographs taken all over the world. Make your Caucasus stand out, or at least make it differ from the American Rocky Mountains or any other highlands. This task is in fact very demanding, and probably crucial.

KK: Anton, what is “The Range Project” as of today? What is happening to the album and other creations? What is available today and what kind of work is underway?

AL: Presently, The Range Project is still in the production stage. Jointly with our partners, the Northern Caucasus Resorts JSC, we spent a year and a half—almost two years—filming and photographing over the course of fifteen or so expeditions, which actually covered the entire territory of the North Caucasus. Of course, it wasn't a linear journey, and it never is, in such large and logistically complex projects.

These expeditions formed a kind of a mosaic that would fill out along the way, forming an artistic, entirely original picture. A spectator can get an impression that the journey is linear because of how it's presented, but in fact it's not true. Tracing expedition routes is one of the most exciting parts of any major project. Now that the shooting period is over, we have entered the stage of post-production, more or less.

The first result is a large photo album. Regrettably, there are a very limited number of prints, and we're really hoping to make it available for the general public by issuing a larger number of copies over the next year.

The second part of the project, which I find very important, is the film I made as an independent producer, co-director, and partly anchor, like it was with all of my other original films about Russia. Currently, it exists as footage ready for post-production and editing. Ideally, I see it as a two- or three-episode film, semi-fiction and semi-documentary—an unprecedented creation about the North Caucasus.

The third part is the exhibition, as the project is worthy of a most extensive display. What I see is a major exhibition of 300–350 large-size works that can be exposed in a hall the size of Moscow's New Manege or the Engineering Building of Tretyakov Gallery. And, last but not least, exhibitions must be held in the region itself, in the North Caucasus. One of my principal goals is making such projects accessible to the public, both in Russia and abroad. Photographers have a limited number of traditional, conservative ways of presenting their works to the public: a book, an exhibition, print media coverage, and sometimes, although not often, films. All of them are complex and costly, and this during a recession [in Russia].

I'm generally averse to the Internet, but I've begun to realize that the Web offers exceptional opportunities. We are now launching a [long-read] dedicated to the project and pages on social networks, in order to present our work to the largest audience possible and receive feedback. In our case, we also have a very special audience: the peoples of the North Caucasus, a region with an ardent commitment to national self-identification and local customs, and an interest in attracting the outer world's attention. Without doubt, it imposes certain extra obligations on anyone who works in the Caucasus.

2 comments

No one can ever truly explain aggression; because it’s built into every life form, and will result in our having acquired all we need to transcend this planet when we need to. The sooner we comprehend this ruse on Nature’s part to extend herself beyond Earth, the sooner we can drop the pretext that war has any validity other than to groom our species as a fighting force for the planet’s future life. So, GOOD FOR US!

Now, let’s stop killing each other; it’s not improving the species and it’s expensive, to boot. .