A Kyrgyz girl near the ancient heritage site Tash-Rabat. Wikipedia image.

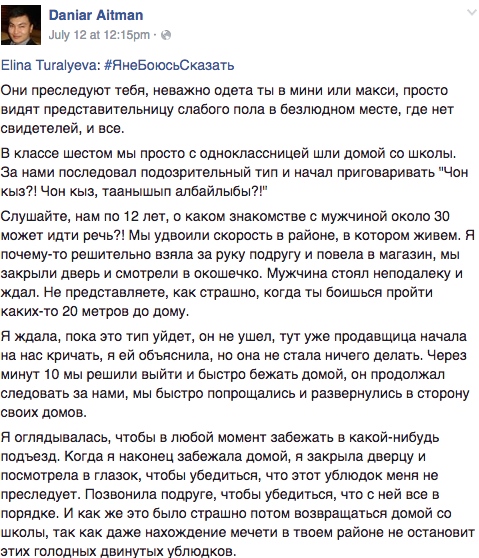

Meet Daniar Aitman, Kyrgyzstan's unlikely — read ‘male’ — hub for stories posted under the “I am not afraid to speak” (#яНеБоюсьСказать) hashtag, an anti-gender discrimination and anti-sexual violence campaign that began in Ukraine and has filtered into other parts of the former Soviet Union.

Or maybe it should not be a surprise that Aitman, who describes himself as a feminist, has spearheaded the Kyrgyz arm of this campaign, after collecting for over a year stories from female victims of harassment and discrimination on his Facebook page.

With harassment of women pervasive in the Central Asian country and many male public figures openly discriminatory towards the opposite sex, speaking out comes at a greater cost for women than for men, a fact Aitman himself readily acknowledges.

In an interview with Open Asia Online Aitman explained the reason for his feminist activism that has seen some male Facebook users accuse him of working as an undercover agent of the West employed to destroy Kyrgyzstan's traditional values:

Это звучит ужасно, но я рад, что родился мужчиной. Женщина в Кыргызстане стоит дешевле скотa. За кобылу обычную нужно заплатить не меньше тысячи долларов. Кобылу sapiens можно запросто средь бела дня приволочь с улицы и запрячь ее пожизненно (или пока не надоест) в своем хозяйстве, задобрив сватов коробкой тошнотворных конфет, парой дрянных китайских рубашек и ящиком паленой водки… Ежегодно в Кыргызстане похищают тысячи женщин. По оценкам исследователей до трети молодых кыргызских матерей были украдены. Кого могут воспитать изнасилованные женщины, преданные своими семьями и обществом? Только следующее поколение дикарей, рабов и жертв.”

It sounds awful, but I’m glad that I was born a man. A woman in Kyrgyzstan is valued less than cattle is valued. You pay at least one thousand dollars for a mare. A mare sapiens [referring to a woman] can be dragged off the street in broad daylight and harnessed for life (or for as long as she is useful) […] Annually, thousands of women are bride-kidnapped in Kyrgyzstan. According to the estimates of researchers, every third young mother in Kyrgyzstan was bride-kidnapped. Who can these women, raped, betrayed by their own families and their own society, possibly raise as children? Only the next generation of savages, slaves and victims.

Located in the heart of Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan has a population of six million people, with women making up over half of the population and many working-age men finding jobs abroad.

On the surface, women have come a long way during a 25-year independence fraught with political upheaval.

In the wake of the shame of boasting one of the world's few all-male parliaments in 2005, a gender quota mandating that at least one-fifth of seats in the legislature be taken up by women was put in place.

And in 2010, after the country's second revolution, Kyrgyzstan became the first country in Central Asia to have a female president in the form of multi-lingual diplomat Roza Otunbayeva.

But from unequal pay through bride-kidnapping and pervasive domestic violence, there are a number of gender-related challenges in the country that are rarely discussed, never mind addressed.

Aitman's Facebook posts — subject to hundreds and sometimes thousands of shares, have gone some way to filling that void.

Typically, before the “I am not afraid to speak” campaign that Ukrainian activist Anastasiya Melynchenko is credited with beginning earlier this month, the posts were mostly testimonies of women who had got in touch with Aitman privately and requested anonymity.

Now, in the spirit of Melynchenko's campaign, many of the posts are non-anonymous testimonies.

Elina Turalyeva's testimony: They hunt you, whether you are dressed in a mini skirt or a maxi skirt, just because you are a member of the weaker sex in a deserted place, where there are no witnesses.

In sixth grade, a classmate and I were returning home from school. Behind us there was a suspicious man, who began to call out: “Young girl, can we get to know each other?”

Listen, we were 12-years-old, how can we “get to know” a man of around 30? We started to run through the area where we lived.

I took hold of my friend's hand and went into a local store. We closed the door behind us and looked through the window. The man was standing and waiting nearby.

You cannot imagine how much fear you are feeling when you are afraid to continue up a road and you are only 120 meters from your house.

I waited for him to leave, but he did not go away. The saleswoman at the store started yelling at us.

I told her [why we closed the door] but she did not care. After about 10 minutes we decided to leave and run home, but he continued to follow us. My friend and I parted company and we ran toward our homes.

When I finally got home, I locked the door and looked through the peephole to make sure this bastard was no longer lurking. I called my friend to make sure she was all right.

After that the walk home from school was full of terror, knowing that even the presence of a mosque in your neighborhood would not shame these hungry bastards.

Aitman's activism — both in writing his own thoughts on patriarchy in Kyrgyzstan and by amplifying the stories of women that have faced abuse — has reaped both praise and criticism in abundance.

One post that he wrote on his blog collected angry responses of male Kyrgyz commenters from his wall or from the comments section under articles written by him:

Эй, блогер.. что ты будешь делать с девками, продающими себя на улицах и в саунах, как ты их с улицы уберешь, если сам под каблуком ходишь? Эй, кыргызские джигиты, если надо, берите по две, по две берите! Пусть лучше в хозяйстве будут работать, чем на улице себя продавать!

Hey blogger… what will you do about the girls that sell themselves in the saunas and on the streets? How will you take them off the streets when you yourself are living under their heel? Kyrgyz men, if you need to, take two [women]! Better that they work as housewives than sell themselves on the street!

It makes no sense to narrow all Kyrgyz men, all Kyrgyz women into any particular category.

Many Kyrgyz families — including in rural areas where the bride-kidnapping phenomenon is most widespread — are paragons of love and respect.

But the prevalence of patriarchy makes it especially important that men as well as women join the call to end systematic sexism and sexual violence in all walks of life.

Writing under one of Aitman's posts one reader wrote:

“….В нашей стране много традиций и обычаев, которые граничат с идиотизмом, но остались еще интеллигенты, которые знают ценность женщины и любви, и я надеюсь Ваша пропаганда ценностей и уважения даст плоды и повлияет на нашу мужскую молодежь и вложит понятия любви к женщинам….”

In our country there are many traditions that border on idiocy but there are still intelligent people, who know value of women and love, and I hope that your propagation of these values and respect [towards women] will help influence our male youth and instil this understanding of love towards women.

But in a column for StylishKG magazine reposted on his Facebook wall, Kyrgyz diplomat and academic Jomart Ormonbekov reflected on how the “I am not afraid to speak” (#яНеБоюсьСказать) campaign had not resulted in many other examples of male feminist activism of the type embodied by Aitman:

Как обычно у нас это бывает еще одна нужная инициатива скатилась до чисто биологического противоборства между полами. Пока #ЯНеБоюсьСказать набирает обороты, в сети женские голоса возмущены молчанием мужских. Возмущение понять можно. О таких вещах говорить вслух в нашем двуличном обществе, как минимум, неприлично, а сказать громко и о себе требует мужества, долгих терзаний и, возможно, поздних сожалений. Поэтому от мужчин ждут, даже и не действий, а хотя бы слов сочувствия и сожаления, но в ответ лишь тишина, или жалкие попытки пошутить.

Мужское молчание не связано с тем, что нам все равно. Мы жадно читаем каждый пост, каждую историю. И нам стыдно. Стыдно, что не смогли предотвратить. Стыдно, что бессильны. Стыдно, что причинили боль. Мы читаем каждое слово, и мы узнаем себя, или брата, или друга. И нам еще больше стыдно, потому что мы боимся сказать.

As usual, another much-needed initiative has led to a purely biological standoff between the sexes. While #ЯНеБоюсьСказать gains prominence, women voices online are indignant at the silence of their male counterparts. That indignation is understandable.

In our bifurcated society it is considered indecent to speak out. To speak aloud and of your own experience requires courage, entails agony and might even cause you to regret later on. For that reason, men should share in solidarity [with women speaking out] words of sympathy and regret, but so far there has only been silence and feeble attempts at humour.

This male silence is not connected to the fact we do not care. We greedily read every post, every story [of the campaign]. And we are ashamed. Ashamed we could not prevent [the violence]. Ashamed of our powerlessness. Ashamed we caused harm. We read every word and we find ourselves, or a brother, or a friend. And we are even further ashamed, because we are afraid to speak.

6 comments