[1]

[1]Pinocchio, the fictional character whose nose grows larger when he lies, is often used as symbol in fact-checking. Art by Enrico Mazzanti (1852-1910). Public Domain.

The morning after the Brexit [2], the referendum on the United Kingdom's exit from the European Union, one of the leaders of the “Leave” campaign shocked the public by admitting he had misled the public on a key issue [3]. When asked whether the UK's alleged £350 million weekly contribution to the EU would be directed to the National Health Service [4] instead, the former UK Independence Party [5] (UKIP) leader Nigel Farage [6] said “that was a mistake.”

In an interview with ITV’s Good Morning Britain presenter Susanna Reid, Farage said that he couldn't guarantee fulfillment of the campaign pledge, and tried to dodge the issue by claiming that it wasn't an official promise, though the campaign had run advertisements announcing it.

In response, outraged citizens, including journalists, tweeted photos of the ads— posted in conspicuous places like the sides of buses— debunking the lie.

“The £350m was an extrapolation. It was never total.” -Iain Duncan Smith pic.twitter.com/hqAQuXsuLn [7]

— Ciaran Jenkins (@C4Ciaran) June 26, 2016 [8]

This incident illustrates the need for more political fact-checking as a public service, to enable the voters to make more informed and rational decisions about matters affecting their daily lives.

The rise of global fact-checking in reaction to political and media manipulation

Fact-checking is supposed to be a part of the normal journalistic process. When gathering information, a journalist should verify its accuracy. The work is then vetted by an editor, a person with more professional experience who may correct or further amend some of the information.

Some big news organizations even have special departments devoted to double-checking the work of their journalists and editors. This form of fact-checking entered popular culture in the 1988 film “Bright Lights, Big City [9]“, in which, Michael J. Fox plays a glamorous fact-checker employed in “a major New York magazine.”

[10]

[10]In the 1988 film “Bright Lights, Big City”, Michael J. Fox played a fact-checker at “a major New York magazine”. Source: Wikipedia, fair use.

In the decades after the 1980s, most news outlets around the world could not afford—or simply did not consider it necessary—to have fact-checking department, or even a single fact-checker playing the role of devil's advocate [11] in the newsroom.

But the need for fact-checking hasn't gone away. As new technologies have spawned new forms of media which lend themselves to the spread of various kinds of disinformation [12], this need has in fact grown. Much of the information that's spread online, even by news outlets, is not checked, as outlets simply copy-paste—or in some instances, plagiarize—”click-worthy” content generated by others. Politicians, especially populists prone to manipulative tactics, have embraced this new media environment by making alliances with tabloid tycoons or by becoming media owners themselves.

In recent years there has been a drive to fulfill the need for political fact-checking [13]. It comes from two general directions. The first includes journalists who, after years in the trenches, also went into academia, in an effort to uphold the standards of their profession. The second includes civil society organizations that aim to utilize the new technologies to generate democratic reform by forcing their governments to become more transparent and accountable, thereby countering corruption. A number of such projects, combining civil activism and media development, have emerged around the world.

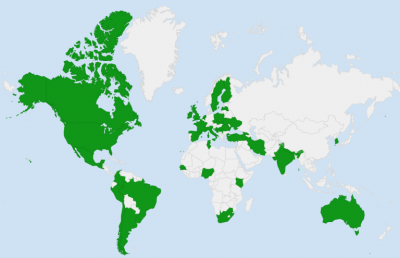

[13]

[13]The green areas represent countries with fact-checking initiatives, based on Duke Reporters’ Lab database and integrated with more recently launched sites (June 2016). Map by Alexios Mantzarlis/Poynter, used with permission.

Over 100 fact-checkers from 40 different countries took part in the recent Global Fact-Checking Summit in Buenos Aires, Argentina [14] (#GlobalFact3 [15], June 9-10). Organized by the US Poynter Institute, [16]the gathering also served to strengthen Poynter's International Fact-Checking Network [17]. (Disclosure: I attended the Summit as representative of Metamorphosis Foundation, which runs two such projects in Macedonia: TruthMeter [18] and the Media Fact-Checking Service [19].)

Organizations involved in fact-checking start by developing a methodology that serves as a blueprint for their analytical products. One of the key discussions at the Global Fact-Checking Summit was about developing a shared code of principles that would push fact-checkers towards ever-greater transparency, and consolidate readers’ trust in the the fact-checking instrument.

TV fact-checking as the next frontier

The primary audience for fact-checking activities is online. Research done in Macedonia suggests that the target for such content is highly-educated younger people. Globally, however, this demographic category represents only a portion of the voting public. In order to reach wider audiences, fact-checking projects collaborate with other kinds of media.

Some fact-checking projects have made inroads into the medium that's still a dominant opinion-maker among older and less educated populations—television. There are several successful examples, such as the Spanish El Objetivo [20] and the Italian Virus [21]. When backed up by the support to enable high quality production, these examples show that fact-checking can be an engaging form of edutainment [22].

Most importantly, participants in such initiatives are ready to share their knowledge. In May 2016, producers of the most popular European TV shows involved in fact-checking the truthfulness of public speech, along with editors and journalists from regional fact-checking initiatives gathered in Sarajevo for a workshop as part of the annual POINT Conference [23]. The NGO Why Not, the organizers of the conference (and also run the Bosnian version of Truthmeter), produced a short online documentary summarizing the various aspects of TV fact-checking [24].

In the video, Poynter's Alexios Mantzarlis [25] explains that the goal is to help fact-checkers “translate what they do online into material that is interesting on TV. . . . So it is important to do something that doesn't just reach people who are anyway curious and are looking for this kind of verification, but who may not be getting this content otherwise.”

Patrick Worrall from Channel 4 Fact-Check explained that:

We need fact-checking for a number of reasons. One, politicians tell lies, unfortunately. They always have and they always will. And people sitting at home often want to check what politicians are telling them, and they don't have the time and resources to do all the hard work. So people like us are supposed to go out and check them. And we know, there's some evidence, that when people in the public life are fact-checked regularly, they become more honest, they become more careful about what they tell the public.