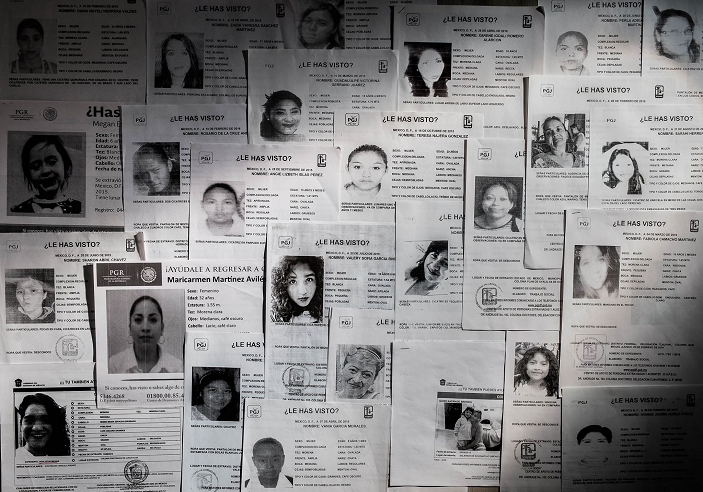

“Missing Women.” Photo by Luis Sandoval for El Universal. Published with permission from CONNECTAS.

This report was written by Daniela Guazo for [Mexican newspaper] El Universal, as part of the Mike O’Connor Scholarship for the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and the Initiative for Investigative Journalism in the Americas, which partners with the ICFJ and CONNECTAS. This version is published by Global Voices thanks to a content sharing agreement with this medium.

From 2002 to 2015, more than three thousand women disappeared in Mexico’s capital. Although no one is sure of their whereabouts, their families have not lost hope in finding them. Meanwhile, authorities only consider them to be “absent.”

Ana Paola Franco recently turned 21, but this time she didn’t blow out candles on a cake surrounded by her family. The tradition was broken. In her room are her clothes, her bed, and her big stuffed animals — reminders of the life she led. Everything remains intact since February 9, 2016. That was the last day the young woman left her house to go to work. She said goodbye to her brother with a simple “see you tonight.” That never happened.

After not hearing from her for more than 24 hours, her name was added to a flyer along with her picture and distinguishing marks. These cards, issued by Mexico City’s Care Center for Missing or Absent Persons (Capea), are no longer news. Her case was one of 187 reports of missing women that were filed between January and March of 2016 in Mexico City.

Ana Paola’s father went to Tlalpan’s Public Ministry offices. There, he ran into the biggest obstacle that families in a similar situation face: Ministry employees told him that “because she is of legal age, you must wait at least 48 hours to start the investigation.” He left the office with the fear that no one would look for his daughter.

Photo by Luis Sandoval for El Universal. Published with permission from CONNECTAS.

This young woman’s name is just one of the many that make up the city’s database of missing persons. El Universal’s Journalism Data Unit standardized these records up to March 2016 and they are available as a resource on Mexico City’s Attorney General’s Office website to determine how many women are missing in the capital.

Of the 6,878 reports the site has counted up to this point, 3,054 are women. Filing dates range from 2002 until the end of 2015. José Antonio Ferrer, Capea Director, ensures that the website is constantly updated and when someone is found, they are removed from it.

Below, along with the file number, is the word “ABSENT.” This label has led to more than three thousand cases not being the priority of the capital’s officials. Ferrer is blunt in describing what the institution in charge does:

Nosotros no conocemos de desaparecidos. Son personas extraviadas o ausentes.

“We aren’t aware of missing persons. They are lost or absent.”

In six out of ten, or 1,972, records found on Capea’s site, the young women were between 13 and 20 years old when they went missing. The boroughs of Iztapalapa, Gustavo A. Madero and Cuauhtémo make up 44% of these cases.

Between 2009 and 2011, there is an annual average of 300 unresolved cases. In 2012, this figure reached 432 reports of females who failed to return home. This figure, far from diminishing, indicates significant increases. In the records from 2015 are the names of 522 women who remain missing, according to the data available on Capea's website.

Mexico City’s Observatory against Human Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation warns that the authorities do not want to admit the problem. “The city is starting to generate its own trafficking victims and the government is ignoring it,” said Gerardo Nava and Víctor Núñez, members of this organization that has been investigating these cases for more than four years.

But for the mothers, the most difficult question is knowing when to stop looking. Alma Estela, Ana Paola’s mother, calmly, but tearfully says:

No vamos a parar. Aunque me entreguen un cuerpo al cual llorarle, pero necesito saber en dónde está mi hija.

We will not stop. Until they give me her body to mourn, but I need to know where my daughter is.

Each member of the Franco Aguilar family clings to something. A final message. The memory of watching movies on the weekends. Having breakfast together: “It was just the four of us,” says her father. Oscar forces himself to believe that one day the quartet will again be complete.

If you want to know more details of the situation faced by thousands of families and see the victim’s individual faces, view the slideshow Ausencias Ignoradas (Ignored Absences).

To read the full report, click here:

2 comments