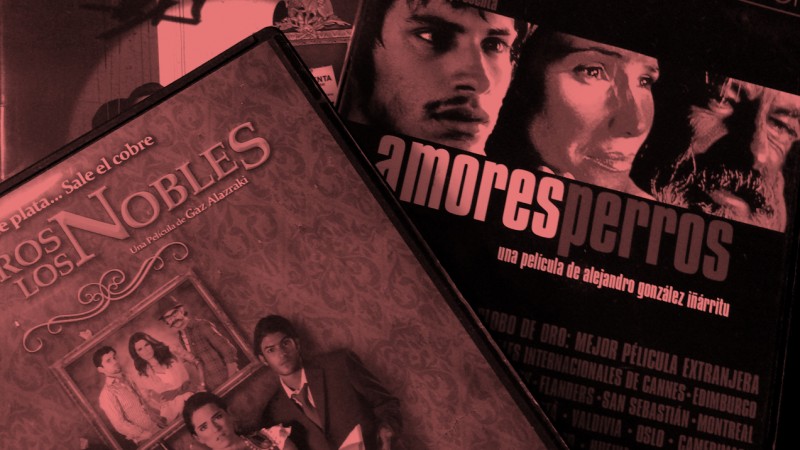

Covers of well-known Mexican films. Image by Juan Tadeo.

Mexican films that exploit classism and social inequality are some of the biggest hits at the box office. The latest example of this phenomenon is the recent release ¿Qué culpa tiene el niño? [1] (“Why Blame the Kid?”).

As previously [2] reported on Global Voices, economic disparity and poverty have cultivated rising class tensions in Mexico, leading to widespread perceptions that more affluent groups and individuals treat the rest of the population arrogantly. Visible extravagances and consumer excess only makes the country's inequality more obvious.

It's by no means trivial that the film “The Noble Family [3]” was a record-breaking success at the box office when it was released in 2013. The movie is about a fictitious family at the top of Mexico's socioeconomic ladder and the complications the family faces as it tries to live like the rest of the country. Specifically, the family members have to work poorly paid jobs. One character finds a job in a bank, another drives a public bus, and a third works as a waitress, where she's forced to wear a skin-tight miniskirt on the job.

In May 2016, approximately 1,100 movie theaters in Mexico screened the debut of “Why Blame the Kid?” by the director Gustavo Loza. According to the newspaper Milenio [4], the movie attracted a bigger audience that weekend than “The Angry Birds Movie” [5] and the multi-million dollar Hollywood super production, “Captain America: Civil War [6].” The winning formula is the same as always: poke fun at classism in Mexico. Movie critic Alejandro Alemán says [7] it boils down to a single gag:

El humor en esta cinta versa sobre un solo gag. La diferencia social entre Maru y Renato así como el choque de clase que presupone la reunión de ambas familias. Mientras Maru es hija de un importante diputado (Jesús Ochoa haciendo su personaje de siempre) que vive en una cuasi mansión, Renato vive en una unidad habitacional con su mamá (Mara Escalante, haciendo de su personaje una revisión de otro similar que hace en la televisión); mientras Maru tiene un trabajo respetable en Santa Fe, Renato tendrá que meterse de repartidor de pizzas; mientras la familia de Maru bebe champaña, la familia de Renato bebe tepache.

The humor in this film is all about one gag: the social differences between Maru and Renato and the cultural clash presupposed by the union of their families. While Maru is the daughter of an important government official (Jesús Ochoa playing his classic role) living in a quasi-mansion, Renato lives in a housing unit with his mom (Mara Escalante playing a character very similar to one she plays on TV). While Maru has a respectable job in Santa Fe, Renato has to work as a pizza delivery boy. While Maru's family drinks champagne, Renato's family drinks tepache [8].

(Note: Santa Fe is an area in Mexico City that has gone through a gentrification [9] process in the last decade due to the construction of office buildings and high-end commercial spaces. On the other hand, tepache is a drink made from fermented pineapple, which is becoming less popular. It is normally reserved for people with limited economic resources.)

The Mexican public's morbid fascination with romantic relationships between people from different social strata was central to the 2002 film “Amarte duele [10]” (“Loving You Hurts”) and innumerable other Mexican movies, dating back at least to 1959, Alemán points out.

Social media users like Rufián warned viewers about classist tropes in “Why Blame the Kid”:

Ps la de Qué culpa tiene el niño sí logra estar divertida. A pesar del clasismo y hasta cierta misoginia elegante.

— Rufián (@rufianmelancoli) May 14, 2016 [11]

Well, “Why Blame the Kid” turns out to be fun. Despite the classism and, to a certain extent, backhanded misogyny.

— Rufián (@rufianmelancoli) May 14, 2016 [11]

Francisco Blas, meanwhile, noted that the reason we go to the cinema is to have fun:

¿Que culpa tiene el niño?, quizá si sea un remake clasista pero divertida y cómica al final a eso vamos al cine no?, a divertirnos.

— Francisco Blas Ⓜ️ (@iQueBlas) May 15, 2016 [12]

Why Blame the Kid? Maybe it is a classist remake but it's entertaining and funny and that's why we go to the cinema, right? To have fun.

— Francisco Blas Ⓜ️ (@iQueBlas) May 15, 2016 [12]

It's worth mentioning that the popular Mexican film industry receives little recognition outside of the country, thus only a few high-quality films ever make it across the border. You can count stand-out Mexican films on one hand. Perhaps the most important of which is “Amores Perros” [13] (2000), directed by the now award-winning and internationally recognized Alejandro González Iñárritu [14].

Also, the work of Luis Estrada [15] shouldn't go unmentioned, with its well-timed critique of corruption and power of the political class both in “Herod's Law” (1999) and “The Perfect Dictatorship [16]” (2014), among others. But that's about it. The bulk of commercial Mexican cinema has been dominated by romantic comedies adorned with the deeply rooted classism that characterizes (and seemingly appeals to) a large majority of Mexican society.

Satire has always spiced up critiques about undesirable behaviors that we should try to overcome. In Mexico, classism is used as sales hook that brings people to the cinema and makes them laugh for a while. Nevertheless, sometime soon, this same classism needs to be addressed seriously as a problem that doesn't make everyone laugh but instead has caused pitiful episodes of discrimination, abuse of power, and assaults against public servants in the last few months, as Global Voices has reported previously. [17]