Elementary school graduation ceremony in Japan. Photo by Nevin Thompson.

After spending most of the past 20 years living in Japan, to me 2015 seemed like a turning point for the country. 70 years after the end of World War II, and despite massive demonstrations all over the country, in September 2015 [1] Japan's ruling coalition, led by Shinzo Abe and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), used cloture [2] to force the implementation of new security laws that will allow Japan to engage in military action outside of the country. Thanks to this new legislation, Japan effectively renounced 70 years of pacifism and can now go to war again.

For many of my friends—long-term “foreign” residents with deep connections to and equally deep knowledge of Japan—the Abe government's relentless effort to “make Japan great again” was like a nightmare come true. The country we had all come to love seems like it might be disappearing, leading us to ask whether our children will have a future here.

The forced passage of the new security legislation was simply the most striking example of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's steady attempt, over the past three years, to incrementally shift Japan rightward [3]. Abe is perhaps the first prime minister to directly and loudly criticize the media [4], and has been accused of trying to turn NHK, Japan's nominally impartial national broadcaster, into a government [5] mouthpiece [5] that promotes the current Japanese position [6] on regional territorial disputes with South Korea, Russia, China and Taiwan.

“Let's take back Japan.” LDP. Image widely shared on social media.

For the 20 years following the end of Japan's Bubble economy in 1991 [7] the main national focus had been on kickstarting the economy, with no attention paid to nationalism or changing the country's constitution.

For me and my family, this 20-year-long “Lost Decade” was not a bad time to be in Japan. Deflation meant cheaper grocery bills and bargains on clothing—it is much cheaper to raise a family in Japan than Canada. Government stimulus programs poured money into shiny new infrastructure projects all over the country, which meant better public transport, more museums and, in the rural region where we live, shiny new department stores.

Even after I moved my family back to Canada in 2004 in search of a better job and what I thought would be a better education and opportunities for our children, within a year or two we found ourselves back in Japan for several months every year. As a writer, I can work anywhere, and we found that our sons could cross cultures and attend school easily in both Japan and Canada. We wondered whether we should move back to Japan full-time.

The March 2011″triple disaster [8]” in Tohoku changed everything: the massive earthquake triggered a tsunami that in turn caused a serious nuclear accident in Fukushima. The panic and chaos of the Fukushima disaster would cause yet another seismic shift in Japanese politics. The Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) was in power during the crisis, and many Japanese citizens were disappointed and infuriated by the DPJ's response to both the nuclear crisis and the massive devastation wrought by a tsunami that had destroyed more than 1,000 kilometers of coastline.

Promising to “take back Japan,” Shinzo Abe and the LDP swept back into power in 2012. No one thought Abe would last more than a year. Typically, because of factional politics, prime ministers are figureheads, and rarely serve more than a year. But by the summer of 2015 Abe had become one of the longest-serving prime ministers in nearly a decade. And he was steadily advancing his agenda.

Abe has long between identified with Japan's fringe but powerful nationalist constituency that includes players such as the Nippon Kaigi [9] organization, of which many prominent LDP parliamentarians are members. Abe's newest slogan, “A Society in Which All 100 million People can be Active” [10] bears a striking resemblance to a fascist wartime slogan, “One Hundred Million Hearts Beating as One” [11] (一億一心). And, somewhat dishearteningly, a certain nostalgia for World War II seems to have developed in Japanese culture. In recent years, perhaps in response to what is widely perceived to be aggressive behavior by China, books and movies [12] that look back nostalgically on the heroism and self-sacrifice of World War II have become more common in Japan.

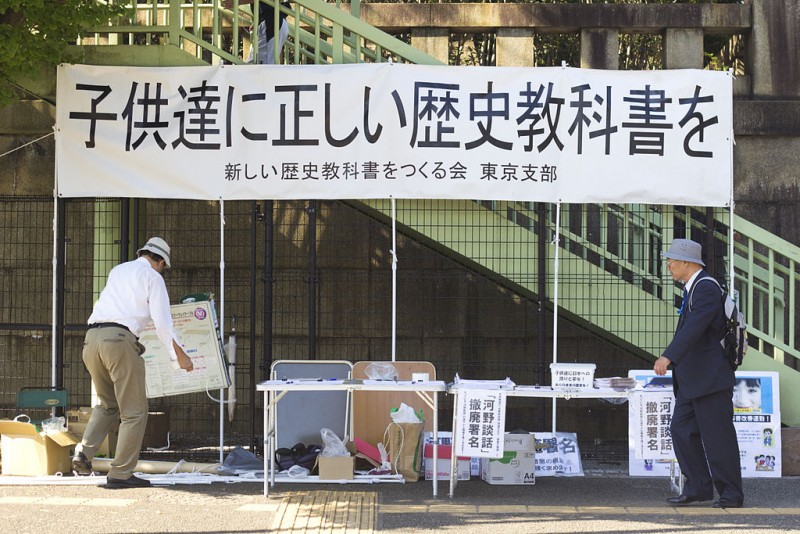

It’s also apparent that the Abe government is trying, in some ways, to implement a more nationalist school curriculum in Japan. Based on a directive from the Ministry of Education, Japanese textbook publishers proposed removing the term ‘comfort women’ [13] from textbooks. Besides plans to formalize “moral education” [14] (道徳, doutoku), earlier in 2015 the Ministry of Education decreed that Japan's history, as taught in schools, should reflect the government's position on history and territorial issues [15].

[16]

[16]”Let's make sure our children have a textbook that tells them the truth about history.” Image from Wikimedia user Japanexperterna.

This is not the first time [17] the Japanese government has attempted to use school textbooks to advance historical revisionism, and I wonder how effective this move it doing to be. It’s important to note, for instance, that there is no single history textbook that every school in Japan is obligated to use. Individual school boards can choose from a ministry-approved list of books, and historically, many have refused to use textbooks that appear to blatantly whitewash history. At the schools my children attend for several months each year, little appears to have changed since I myself taught in the Japanese school system 15 years ago. There are no patriotic slogans and no pictures of the emperor in every classroom as there had been before and during the war.

It’s also true that given the way history is taught in Japan, there is likely to be little opportunity to explore competing points of view in the classroom. Japanese textbooks are designed to prepare students for passing tests, not to transmit government propaganda. [18] Rote learning plays a large role in the Japanese education system: there is a test, you study for it, and there is a right answer and a wrong answer.

This is not to say that the Japanese approach to education is unsophisticated. In elementary school there is an emphasis on project-based learning, student-led learning and leadership. And from a practical point of view, it's more efficient to use brute-force rote learning to master the 2,000 or so kanji (Chinese characters) students need to know by the time they graduate from high school.

While the information-dense texts used in schools tend to offer a conventional national narrative of the past two thousand years of Japanese history—and one which is generally reinforced in popular culture, notably in engaging rekishi manga historical comic books on the shelves of libraries and bookstores across the country,

It’s still debatable whether in the 21st century, the government is somehow going to be able to program what children think by changing a few words in a history textbook. For one thing, history is taught by teachers who, as human beings, bring their own values into the classroom and the best teachers give students the ability to investigate and explore history themselves.

So, I'm not very worried that Shinzo Abe's textbook reforms are going to teach Japanese students a warped view of history. The purpose of Japanese textbooks, after all, is to help students pass high school and university entrance examinations, which revisionists cannot directly control. On top of that, history can be hard to teach, and students are only just starting to understand what happened in the past.

And I even have reservations about how my son is taught history when he’s at school in Canada. While Canada is often regarded as a peaceful, tolerant and progressive country, the reality is that there is a de facto system of apartheid [19] here that we never learn about in school: indigenous Canadians and post-colonial “settlers” [20] rarely interact with each other. The injustice, for instance, of Canada's residential school [21] system is only just starting to be formally taught [22] in schools.

History is ultimately about people, whose individual stories can never all be told in a government-approved textbook.

Instead, it's important to help our children remain curious, to ask questions, and to explore history on their own. In free, democratic and resilient societies such as Canada and Japan where there are few limits on freedom of speech, the problem isn't indoctrination by the state. The challenge we face is apathy. After writing about a recent agreement reached between the governments of Japan and South Korea to resolve the “comfort women issue”, I was surprised at how little interest or curiosity was expressed regular Japanese people.

So, wherever in the world my family ends up, my goal as a parent is to help my children at least try to explore the past, recognize injustice and speak up, in order to help make things better.