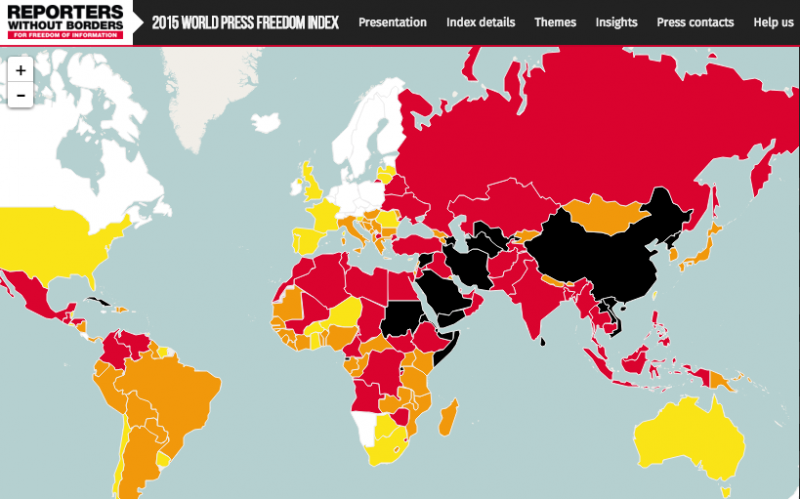

China press freedom was at the lowest level in Reporters Without Borders’ 2015 index. Screen capture.

“In China, a journalist is an occupation for being mocked and menaced,” a former journalist in Beijing once told this author.

From reporters derided by the public for their subservience to the party, to investigative muckrakers intimidated for exposing the darker sides of China’s economic miracle, all journalists in China are hobbled by the absence of a media law defining their rights and responsibilities.

A March 10 press conference for the 14th National People’s Congress (NPC), an annual session of China's main legislative body held in Beijing, threw the debate about China's lack of a comprehensive media law into the public spotlight once again.

A Chinese-American journalist from The China Press of the United States hit delegates at the congress with a barrage of questions:

我的问题是:新闻法已经说了几年,但是请问目前是否有时间表?如果有的话,可以公布一下吗?没有时间表,是为什么? 为什么中国的新闻法出台这么难?

My questions: the press law has been in discussion for many years, I am wondering if there is any timetable for [developing legislation]? If there is one, could you publish it? If not, what is the reason? Why is it so hard to create a press law for China?

A NPC delegate swiftly brushed the questions aside, however: “Does any foreign journalist want to question our legislature's work? If not, today’s news conference ends now.”

A clip of the exchange broadcasted live on state-owned Chinese Central Television (CCTV) sparked a flurry of commentary on China's Twitter equivalent Weibo.

Wang Zhijun, an investigative journalist, was disappointed by the NPC delegate’s response:

从我2000年做新闻记者起,我们就呼吁出台《新闻法》,保障记者采访权益不受肮脏官员侵犯。现在16年过去了,我的师弟师妹们仍在呼吁《新闻法》,我看到这里,心中一阵悲凉。

Since I became a journalist in 2000, we have been calling for a press law that can protect journalists and their [right to] interview from pernicious officials. After sixteen years, my younger colleagues are also fighting the same battle. I felt much woe when watching [this clip].

Worsening media environment

Before posing those questions at the congress, the same journalist raised the case of reporter Zhang Yongsheng, as an example of the deteriorating environment for Chinese journalists.

Zhang Yongsheng, who worked for the Lanzhou Morning Newspaper based in Gansu province, northwestern China, was well-known to locals for his years of investigative reporting.

Zhang was detained by police when reporting a fire accident in Wuwei, a city near the capital of Lanzhou in January.

Despite receiving a warning not to report on the fire, he still set off for the scene, where police were waiting to arrest him.

The Gansu provincial judicial department subsequently ordered Zhang's detention on sex trafficking and extortion charges dating back to 2009.

Wuwei police finally released Zhang on probation after a month in jail, with the provincial judicial department dismissing his sex trafficking charge but insisting on the extortion charge. Zhang was asked to keep silent thereafter.

The provincial judicial department has not offered any evidence of Zhang's alleged attempts to extort or defraud officials to the tune of 5,000 Yuan (nearly $800), despite calls from journalists and lawyers to do so.

The Chinese judicial system is famous for its ambiguity. Defendants are often coerced into accepting their charge as a condition of release or probation.

One of Zhang’s friends said Zhang was tortured physically and psychologically by police during the interrogation.

The news arm of Tencent, one of China's best-known online portals, noted after his arrest that Zhang’s tenacious reporting had in the past ruffled the feathers of a number of local officials.

At the NPC delegate conference in Beijing, Tu Zhonghang, a journalist with the Beijing News, asked for information about how Zhang's case was developing, but this question was also ignored.

The Committee to Protect Journalists, a non-profit organization based in New York, pointed out in its 2015 annual report that there are 49 journalists in jail in China, a quarter of the known global figure of 200.

Social instability fears

In a 2009 People’s Daily interview, Zhan Jiang, a professor at the International Journalism and Communication School of Beijing Foreign Studies University, explained some of the factors that have stymied the development of a press law.

The Chinese government, Zhan noted, has been drafting a press law since the 1980s.

After the bloodshed following the 1989 Tiananmen Square protest, however, and the collapse of the Soviet Union, drafting work came to a halt over concerns about potential social instability.

Professor Zhan supports the development of a press law:

我国宪法规定,公民有言论、集会、结社和出版等自由。这是很好的原则和规定,但是这些原则具体实施起来很难,这样,《新闻法》的价值就体现出来了,它是体现宪法精神、落实宪法原则的法律。……新闻立法的重要价值在于,可以通过这样一部法律管理新闻界和与新闻界相关的社会领域,赋予新闻界以采访、报道、评论等权利,也让新闻界承担一定的义务,防止它对社会和公民个人造成损害。

The Constitution rules that citizens have freedom of speech, for gatherings, association and publishing etc., which are good principles and rules but difficult to implement [in practice]. The values inherent in a press law can embody the sprit of the constitution and help implement it […] This law can help manage journalism and related social spheres and bestow rights on journalists to interview, report, remark and so on. It also lets journalists take some responsibilities, limiting the damage [immoral or irresponsible journalism] can sometimes inflict on society and citizens.

The huge banner says: “CCTV is sticking to the party line. We welcome your review with absolute loyalty.” (Image from Weibo)

But party hardliners see things differently.

Earlier in February, Chinese president Xi Jinping visited three state-owned media outlets—Xinhua News Agency, the People’s Daily and Chinese Central Television (CCTV), signalling the party's new policy of more stringent control over state media.

Meanwhile, Chen Yun, a former top leader of the Communist Party, believes there is no need to legislate a press law, as it “might allow others to take advantage of us”:

在国民党统治时期,制定了一个新闻法,我们共产党人仔细研究它的字句,抓它的辫子,钻它的空子。现在我们当权,我看还是不要新闻法好,免得人家钻我们空子。没有法,我们主动,想怎样控制就怎样控制。

Under the [pre-communist] Kuomintang’s domination, it legislated a press law, we communist party members carefully studied its wording, seized on it and took advantage of it [to gain the control over China by waging information campaigns]. Now we are in power, I think it is better not to allow for the development of a press law that might allow others to take advantage of us. If there is no law, we take the initiative and can control [media] as we want.