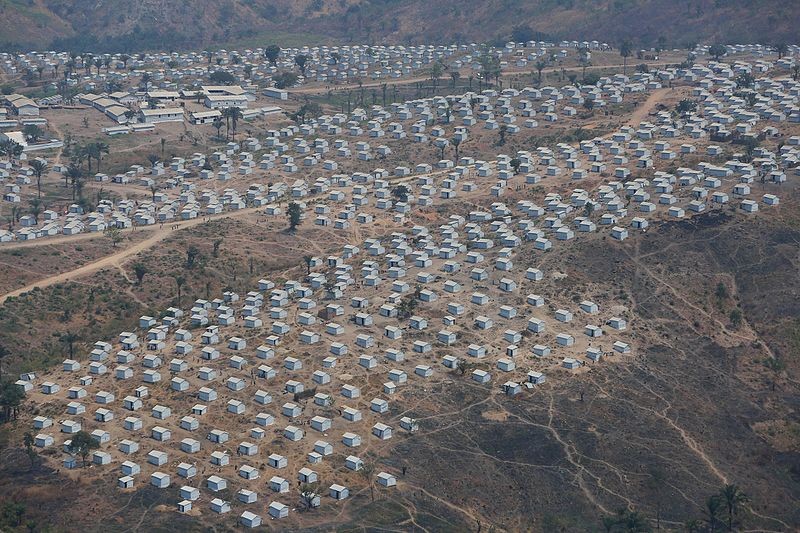

Aerial view of Lusenda Burundian refugees’ camp, South Kivu, DRC. August 2015. Photo released under Creative Commons by MONUSCO/Abel Kavanagh.

Amid ongoing political instability [1], Burundi’s government suddenly announced several goodwill gestures last week.

President Nkurunziza took a controversial third term in mid-2015, leading to protests, repression, insurgencies, and many fleeing as refugees or exiles. Independent radios were shut [2] down, forcing them to take their broadcasts online, and many journalists fled.

The government has strongly resisted international pressure thus far, but these gestures appeared to be good news, taken ahead of United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s visit [3] to the country on 22-23 February, a subsequent [4] visit by a high-level African Union [5] delegation [6] on 25-26 February, and an upcoming East African Community summit.

Some media to return

On February 19, it was announced [7] that the Isanganiro [8] and pro-government Rema radio stations had been permitted [9] to return to air, although this did not apply to the other three main independent radio stations. The returning radios had to sign an “acte d’engagement” — an agreement on conditions — with the National Council of Communication.

Several directors of independent radio stations remain in exile, and the Bonesha [10], Radio Publique Africaine [11], and Renaissance [12]radio stations remain blocked. Coincidentally, this announcement came at the 20th [13] anniversary [14] of Bonesha radio, among those still blocked.

Restarting broadcasting operations faces practical difficulties, however, as equipment was destroyed when offices were attacked during the failed May 2015 coup [15]. Samson Maniradukunda, the acting-director of Isanganiro radio ever since his predecessor went into exile, lamented [16] this while surveying the company's wrecked offices. He estimated [17] the damages to be around 350,000,000 Burundian Francs (US$ 224,581), noting the station's inability to generate revenue after months of shutdown.

The “acte d’engagement” demands that reporting is “balanced” and does not harm the country’s “security”. Open to interpretation, this leaves the possibility of reporting being controlled. Having two radio stations back on air is certainly positive, but it remains to be seen how freely they will be able to report.

Scepticism remains

On Saturday 20 February, 15 [18] of 34 international arrest warrants were lifted, including [19] the one on Iwacu [20] website’s Antoine Kaburahe. The official letter, shared [21]by SOS Médias Burundi, states simply that the original reasons for the arrest warrants “no longer persist”.

In a press communique [21], the CNARED opposition movement described the lifted arrest warrants as an attempt to divert international attention from both the UN visit and the possible EU sanctions; it stated that the best “gauge” of progress would be annulling all arbitrary judicial proceedings.

The government agreed to receive more African Union human rights observers, as well as three UN human rights investigators. Following Ban Ki-moon and President Nkurunziza’s meeting, the freeing of 2,000 prisoners [22] was also promised. The increased number of arrests during the crisis has added to already crowded [23] prisons.

However, shortly after Ban Ki-moon’s meeting, uncertainties [24] emerged over the number of prisoners to be freed. It also became apparent [23] that the government essentially excluded those arrested during this crisis. Similarly, online commenters were sceptical about the safety of released political prisoners:

@SOSMediasBDI [25] hope they will nor follow them and kill them at night

— stanley owuor (@stanleyowuor1) February 23, 2016 [26]

Notably, the president denounced [27] hateful speech, some of which has had worryingly ethnicized and confrontational tones during the crisis:

No hate speech or songs against @paulkagame [28] during ongoing demonstrations, urges @pnkurunziza [29]. All we need is peace b/w #Burundi [30] & #Rwanda [31]

— Willy Nyamitwe (@willynyamitwe) February 20, 2016 [32]

Sanctions and tensions

Economic sanctions have weighed on the government, especially as the European Union (EU) — the country's single largest donor — considers [33] rerouting aid to non-government channels. International aid accounts for around half [34] of the national budget, and the government has increasingly faced financial hardship, which is affecting crucial public services like education [35] and healthcare [36].

Against a backdrop [37]of continued [38]insecurity characterized by violence [39], arrests, and impunity, resolving Burundi's political crisis needs much more than gestures, positive though they are. If those relieved of arrest warrants still fear attacks for example, they may be reticent to actually return. Tensions with Rwanda [40] have also increased, with many expressing anger over accusations of training insurgents.

“Impermeability” to diplomatic approaches

There has also been a lack of dialogue with exiled opposition. Following his meeting with President Nkurunziza, Ban Ki-moon announced [41] promises of such dialogue, but ministers made it clear that this does not include those they accuse of destabilizing Burundi. As before, this leaves the possibility of excluding many groups, undermining any attempt at genuinely inclusive dialogue. Civil society figure Vital Nshimirimana said that many are tired [24] with “impermeability” to diplomatic approaches.

Ministers have bought time before. A prime example was their attendance at peace talks last December in Uganda, followed by their refusal to continue [42] further sessions. The move entrenched their position without making substantial concessions, apparently hoping to simply tire both opponents and international interest. It therefore remains to be proved that such actions indicate any genuine change in approach to the crisis.

Elusive inclusive dialogue

RED-TABARA [43], a rebel group which openly claims responsibility for attacks on security services, and the political opposition CNARED movement have condemned arbitrary grenade [44] attacks that target civilians. Ministers blame “opposition”, conflating various groups, while CNARED accuses the government of creating a pretext to repress opponents. Whoever is responsible, sustained goodwill gestures from all parties — along with dialogue — could open political space and hopefully end the motivation for and deescalate violence against civilians, as well as between security services and insurgents.

USA’s special representative, Thomas Perriello, hoped these gestures would be followed by concrete [27] actions:

Next 10 days are crucial for #Burundi [30] government to show concrete results on AU monitors, regional talks and opening political space. (2/2)

— U.S. Special Envoy (@US_SEGL) February 21, 2016 [45]

This hope however, was met with much scepticism:

@US_SEGL [46] Then what will happen?Statements?Another visit?Statements?Another visit/community works?Statements?

— Paul Burundi (@AnotherRoar) February 22, 2016 [47]

@US_SEGL [46] honestly, you really believe something is going to change or you haven't measured the magnitude of the crimes & future development?

— Albert Rudatsimburwa (@albcontact) February 21, 2016 [48]

An African Union delegation, headed by South African President Jacob Zuma [49], met with the government, internal opposition, and civil society leaders to discuss their differences and resolve the Burundian crisis. However, opposition figures expressed concern about the delegation's ability to achieve a broad dialogue outside of Burundi.

Charles Nditije of the UPRONA [50] party — a rare remaining opposition politician — even said [51] that the African Union delegation was simply legitimizing the government’s position, noting that Zuma had excluded the topic of Nkurunziza's contentious third term [52] from discussions. If goodwill does not outlive diplomatic visits, the violence in Burundi may continue to escalate.