Image of public transport in Lima. Taken from Flickr account of Jorge Leal under Creative Commons licence.

This post was originally published on Juan Arellano's blog ‘Globalizado’ and is republished here with permission.

Residents of Manchay in the southeastern Lima district of Pachacámac blocked access roads to their neighbourhood on February 1 in protest against the Integrated Transport System of Lima's new shuttle buses known as ‘Blue Routes’, which were introduced on 28 January.

The residents say the new shuttle buses mean they will be forced to pay more for public transport. Fares on the privately owned vehicles — combis, a type of privately owned mini bus, and microbuses — that served as public transport in the absence of government-run options were 0.5 Peruvian soles (about 0.15 US dollars). The official new shuttle buses, which service the same routes, however, will charge 1.2 Peruvian soles (about 0.35 US dollars).

Pobladores bloquean acceso a zona de Manchay en protesta a corredor azul pic.twitter.com/b0uiC7v8Vt

— Martín Málaga (@martinmalaga5) February 1, 2016

Residents block access to Manchay in protest against the ‘Blue Routes’

Pobladores de Manchay bloquean la av. Víctor Malásquez como protesta contra el corredor azul. @RPPNoticias pic.twitter.com/NdCP9tCPXi

— Katherine Soto G. (@Katherin3Soto) February 1, 2016

Manchay residents block Avenida Victor Malásquez in protest against the ‘Blue Routes’. @RPPNoticias

Confrontations with police soon erupted and resulted in at least 40 injuries that day, which brought the neighbourhood medical post to a standstill. The volume of patients was such that various people had to be diverted to medical centres in neighbouring districts.

#Urgente Personas en los cerros esperando a la policía, sigue bloqueado el acceso a Manchay. pic.twitter.com/qptCMgSu6P

— Luis Enrique Rosales (@LuisRosalesPeru) February 1, 2016

#Urgent People in the hills waiting for police's arrival, still blocking access to Manchay.

Policia en helicóptero lanza bombas lacrimógenas en Vía Solidaridad para dispersar manifestantes en Manchay. pic.twitter.com/LS0XGoHrsM

— Luis Enrique Rosales (@LuisRosalesPeru) February 1, 2016

Police in helicopters drop tear gas bombs on Solidarity Way to disperse protesters in Manchay.

The protests continued on February 2, even increasing in volume, as Manchay residents returned to block access roads. A group of them even tried to attack the council building, resulting in the predictable police response. Clashes between protesters and police trying to open the blocked roads and avoid damage to council premises resulted in various injuries and arrests.

#WasapEC | #Manchay: la Av. Víctor Malasquez sigue bloqueada por los vecinos como protesta contra el #CorredorAzul pic.twitter.com/hQi9jqZMCC

— WasapEC (@wasapEC) February 2, 2016

#WasapEC | #Manchay: Víctor Malasquez Avenue remains blocked by residents protesting against #CorredorAzul

Sigue la protesta en #Manchay pic.twitter.com/aOABpI3Uh6

— Joe Olivas Panizo (@jolivp) February 2, 2016

Protests continue in Manchay

Nevertheless, despite the violent protests and police repression, representatives of Lima Council and the protesters were able to enter into discussion, agreeing on a return of the combis and a suspension of the official public transport service.

#Manchay dobló el brazo a Protransporte e hizo respetar “la china” para viajar por la zona

— Joe Olivas Panizo (@jolivp) February 2, 2016

#Manchay socked it to Protransporte [the division of the Municipality of Lima that handles public transport for the city] and commands respect for la china [a nickname for a 50 cents coin, the cost of the ride] to travel in the area

La “china” no murio Manchay la resucito. La protesta del pueblo dio sus frutos https://t.co/YFvTCxKZoi

— josecito ortiz (@vladym1) February 2, 2016

The china is not dead; Manchay has resuscitated it. The neighbourhood's protest has brought results.

La gente de Manchay le dice no a la modernidad y quiere seguir usando el transporte informal por siempre. La Municipalidad de Lima hace caso

— Alfredo Canchanya (@alfredcanchanya) February 3, 2016

The people of Manchay refute modernity and want to continue using informal transport forever: The Municipality of Lima pays attention.

Facebook user Lia Valderrama commented on the thoughtlessness of introducing a reform in the transport system without previous consultation with the population that would supposedly benefit:

cómo le vas a subir más del 100% de pasaje, además le quitas la fuente de economía, su trabajo, a un sector que vive del transporte. Yo entiendo que las reformas no son fáciles, pero no se puede seguir cometiendo la torpeza de (la exalcaldesa) Susana Villarán […] la autoridad no está para imponer reformas no consultadas a la población, la intervención social se da antes de la ejecución para no estar lamentando situaciones y tener que llegar a la desfachatez de enviar helicópteros para atacar desde los cielos a la población que protesta.

How are you going to increase the fare by more than 100%, and at the same time take away the source of economy, in a sector that survives on transport. I understand that reforms are not easy but we cannot continue committing the ineptitude of (ex-mayor) Susana Villarán […] no-one has the right to introduce reforms that have not first been consulted with the public, on top of this regretful situation they have the audacity to send helicopters to attack a protesting population from the skies.

On the other hand, journalist Pedro Ortíz Bisso commented in the newspaper El Comercio that whilst the residents were justfied in their protests, the fact that the council gave in quite so easily to their qualms “may end any chance of future public transport reform” in Lima. A subject which, he added, appears to be of little importance to the current city government..

The precarity of life in Manchay

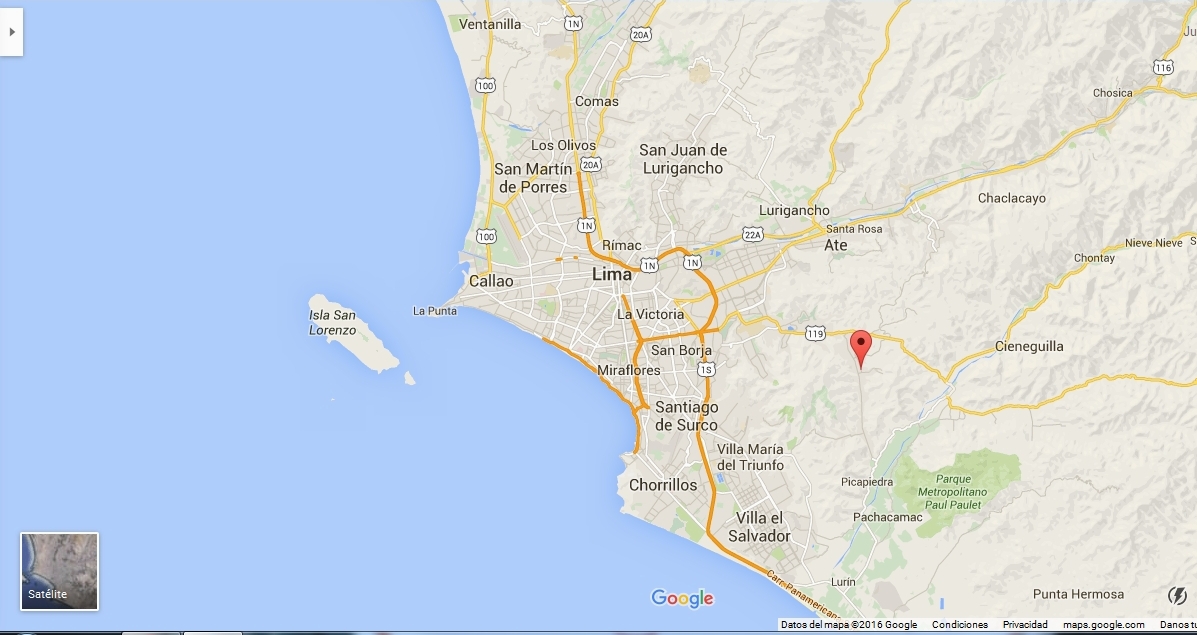

What is it about life in Manchay that makes the residents protest so energetically against a fare rise that would to others seem negligible? Manchay remains a marginal area in Lima, nestled between mountains and desert and, as its absence from the map bears witness, it is not considered to be an area of any importance. Many of its population are originally inhabitants of the Andean areas displaced by the violence perpetuated by the militant communist group Shining Path in the 1980s. The poverty rate is high, yet these residents are forced to spend more on basic services such as transport or water than the residents of far more central areas of Lima. The cumulative effect of this apparently small rise in the cost of transport, over the length of the working week, represents a serious weakening to their purchasing power.

But the problems of Manchay are not limited to transport, water or extreme poverty. Social delinquency is rife and teenagers become gang members as a way to survive. Furthermore, a great number of residents do not own the deeds to their properties. To top it all off, Manchay is geologically the area of Lima most vulnerable to a high magnitude earthquake.

The following video from YouTub user Cristian suelto en la B shows, in his own words, “the best of Manchay — because if we showed the worst, we would be showing simply the worst place to live and one of the poorest places in Lima. You would think that there had been an earthquake, ladies and gentlemen, but not at all, that's just the way Manchay is.”

A few years ago, the blog Cuestiones Sociales (Social Issues) studied the quality of life in some of these areas of Lima, including Manchay, and observed:

Estamos hablando de un asentamiento humano en las afueras de Lima, donde las personas mantienen una vida es muy precaria. La gran parte de dicha población vive diariamente con 5 soles, no tiene la posibilidad de acceder a un servicio tan básico como lo es el de agua potable, viven en casas de material endeble, alejados muchas veces de algo tan simple que todos vemos a diario como una berma asfaltada. El problema es la indiferencia tan grande por parte del estado, el apoyo es muy escaso, las municipalidades no ejecutan el presupuesto anual asignado, no hay una buena administración pública y las personas cada vez se hacen más pobres.

We are talking about a squat on the outskirts of Lima, where the people lead a very precarious life. Most of the population live on 5 soles a day (about 1.50 US dollars) and lack access to services as basic as drinking water. They live in homes built from unstable material, often a long way from things we take for granted, such as surfaced roads. The problem is that the government shows such indifference, there is very little support, the council does not spend the annual budget assigned to the area, there is a poor public administration and the population becomes poorer and poorer.

In reality, these problems are the same in any squat settlement on the outskirts of Lima or of any other large city in the country. In the case of Manchay, however, various groups such as the Catholic Church and NGOs are at least carrying out significant social work intervention to try to better the situation.

Popular discussion of shanty towns like these usually swings between two perspectives. First, that no one is forcing these people to live there, in unurbanised sites with the minimum conditions of a dignified life, and as such, they are responsible for their poverty and suffering. Second, that it was a lack of security or opportunity — in effect, the absence of the state — that led residents to first settle there seeking a better life, and so it is the state's responsibility to look after them.

As is always the case, it is easier to comment, even to judge, from a detached and comfortable life. Nevertheless, it is quite possible to leave this comfort zone and learn about these issues, even from far away. For example, the video below, uploaded to YouTube by Efraín M. Díaz-Horna, was made by a foreigner visitor to Lima and depicts a Chocolatada, an activity (generally around Christmas time) where apart from preparing hot chocolate for guests — usually children and their mothers — organisers often give gifts to the participants.

‘How many hours do people spend on public transport'?

Although calm has now returned to Manchay, as have the combis, it's unknown how long that will last. It has been announced that the protesters who were detained in the confrontations with police will be tried for crimes of disturbance and obstruction of channels of communication under the new law of blatancy, which allows very quick trials (sometimes just a number of days) for crimes which can be proven beyond all doubt.

On the other hand, the residents of Manchay have set a precedent, causing people in other areas of Lima who also feel aggrieved by reforms in public transport to threaten to protest and block access roads as a way of demanding a return to informal collective transport. Some of these unhappy residents are, obviously, the owners and associations of combis and microbuses.

Transport reform in Lima was pioneered by ex-Mayor Susana Villarán to reduce the informality of the existing situation and the number of accidents caused by the private provision of public transport, arising from disproportionate competition between combis and microbus drivers. The reform has ultimately suffered from serious failings in its conception and implementation.

As a final thought, here is a reflection from economist Patricia Teullet in her column for newspaper Peru21, which focuses on topics of public transport and quality of life:

¿Cuántas horas pasan las personas en transporte público yendo y volviendo del trabajo o del centro de estudios? En muchos casos, son dos horas de ida y dos de vuelta, probablemente de pie, y agravado por el calor de verano. ¿Y cuánto gasta cuando tiene que tomar dos o tres vehículos?

¿A qué hora tiene que despertarse esa mujer que en la madrugada o aun a oscuras está limpiando las calles, jalando un enorme basurero? ¿O el padre de familia con un trabajo eventual que depende de la suerte de estar donde debe en el momento adecuado? Sin ánimo de disculparlos por su comportamiento entre irresponsable y salvaje, ¿cuánta presión sienten los choferes de micro cuando tienen que competir en la captura de pasajeros? ¿Y los taxistas que los esquivan dando vueltas durante horas? Todos somos, en algún momento, víctimas y culpables de los accidentes que diariamente ocurren.

How many hours do people spend on public transport, going to and from their place of work or study? In many cases, two hours each way, probably on foot, and worsened by the heat of the summer. And how much does each person that has to take two or three vehicles spend on doing so?

What time does this women who cleans the street in the dark, pulling an enormous rubbish bin, have to get up who in the middle of the night? Or the family man with a casual job who depends on the luck of being in the right place at the right time? Without excusing their behaviour, which ranges from irresponsible to savage, how much pressure do the micro-bus drivers face as they compete to pick up passengers? And the taxi drivers circling up and down for hours, in search of a fare? We are all, at some point, both victims and perpetrators of the accidents that occur everyday.