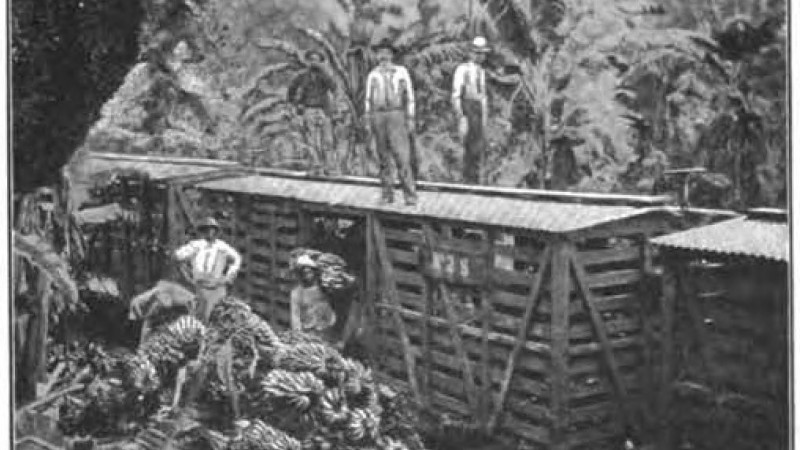

Offloading bananas in Costa Rica in the early 20th century. It was around this time that migrations for the construction of the Costa Rican railroad and the development of the banana industry took place. Without knowing it, many families in Costa Rica were beginning the story of a complex and profound ethnic heritage. Photograph taken from Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

This post, which will be published in two parts, is a version of one previously published on the site Afroféminas. The original post in Spanish can be seen here.

When I was little, my mother told me how she and others had been forbidden from speaking Spanish at home. Stop talking that monkey language, they were told, with “monkey language” referring to Spanish.

And it is from the black population of Costa Rica that I descend: those who came to my country from the British Caribbean at the end of the 19th century, as part of the migrant workforce. They came in search of a better quality of life, both as part of the contingent of workers who constructed the Costa Rican railroad to the Atlantic Ocean, as well as those who worked on the banana plantations. This migration, which began during the latter half of the 19th century, extended over several decades and in the beginning was mainly comprised of young men. Later, whole families came over with the hope of gathering up enough money to later return to their home countries.

With this migration came teachers who founded small local schools whose purpose was to ensure that children learned “proper” English. At the time, and indeed for many years after, Costa Rica’s African descendants would say with pride that they were “subjects of the British Crown” and that their goal during this migration was never to establish themselves, but rather to earn money and then return to their home country, which ultimately never happened.

My parents’ English, though tinged with the musicality and characteristic accent of the Caribbean, was always very well spoken, with excellent grammar and vocabulary. They could move from a conversation in the best British English to colloquial English Creole, which was already “hybridized” by accents and words from Spanish. In that language, or in both, my parents’ generation learned stories, songs, and history.

They learned of mythical images that took the form of animals, learned of supernatural beings that gave hidden lessons, recreated and imagined history, transported us to ancestral places, and promoted communication between grandmothers and grandfathers, uncles and neighbours. They established communication between entire villages with rites and rituals that recreated the experiences of long ago. It was in this language that my mother sang to me my first songs and my father taught me my first prayers.

For them, English not only gave them the privilege of receiving and transmitting culture and ancestral knowledge, but also — according to them — granted them a status that made them feel part of a kind of “royalty” in a country of “peasants and people without education,” by being “subjects” of the British crown.

The fight for language, the fight for identity

The entirety of this story takes place, however, in a country whose official language is Spanish. For this reason, several generations of the black population have been forced to fight to this day in order to conserve the language they brought with them, and with it all of their accumulated history, wisdom, and identity. They struggle against the rejection of the mestizo majority as well as the governments in office, who have for years denied them Costa Rican nationality, despite being born in the country.

Spanish would nevertheless soon become part of this people’s culture, owing to the difficulty of remaining isolated and the necessity and importance of integrating into the Costa Rican educational system. The aim was also to make progress, and for their education to be recognized by the system. Today, my parents and my friends’ parents speak Spanish with a characteristic English accent. My generation, for its part — even those who maintain English as their mother tongue — has already lost this accent, which was at one time so typical.

When it comes to the next generation of African-descended Costa Ricans, English hasn’t always been the mother tongue. Furthermore, the existence of multiple schools and institutions that give English classes has made speaking the language much more common, and no longer the heritage of African descendants as it was 30 years ago.

After a certain point that I can’t remember, my parents decided not to speak to us in English. I don’t know if it was an agreed-upon, conscious decision; simply that my brothers, sisters, and I grew up without being able to speak English. This provoked taunting from our African-descended friends on multiple occasions, and made us feel, at other times, excluded from an ethnicity that was often associated with the ability to speak the language.

The majority of our African-descended friends spoke English, so that we as part of that generation were an exception to the rule. We grew up listening to my mother and father communicate in English, and the communication with aunts and uncles, close friends, and other members of our extended family was always in that language too. Nevertheless, they never communicated in English with us. I tend to think that the reason was related to having migrated to the capital, where we were an obvious minority; or, I don’t know, perhaps it was a timid attempt to protect us, giving us one less reason to be different.

This is exactly where the new part of my story begins.

To be continued in part two.

3 comments