‘I'm not a joke’ is an artistic campaign aimed to defend LGBT rights by challenging stereotypes. The campaign was created by Daniel Arzola and it has been followed and expanded by different activist groups and artists around the world

Gender fluidity, the oppressiveness of social norms, and the dignity of the LGBT community are at the centre of Daniel Arzola’s art and visual campaigns, most notably the project No soy tu chiste (‘I’m not a joke’), which Arzola created as a form of resistance to the everyday violence of living under heteronormativity.

‘I’m not a joke’ came as a response to Arzola’s violent past in Venezuela and evolved through a digital medium to defend and expand the message that paper, in its material vulnerability, could not protect.

“I never wanted to leave my house [because of my violent neighbors, but] I left one day to draw and they attacked me,” Daniel said:

They ripped all my drawings, they tied me to a post, took off my shoes and tried to burn my genitals … I got away, but I stopped drawing . […After this] In 2012 I heard the story of Angelo Prado. […] I felt that could have been me. They burned his arms, legs, back … Something like 60% of his body. [I tried to find him], but it was hard. I actually looked for him three years until I finally found him.

What had happened to Angelo inspired Arzola to start drawing again:

I decided I had to draw in a new format. A format that, if someone broke or tore it up, I could replace it, unlike that time when they attacked me. So I started to draw on the computer.

That same year, a girl was killed for being a lesbian. Her partner was injured. And Angelo’s case was not the only case of incineration in Maracay, a city in the North of Venezuela.

The hate crime against Angelo reminded Daniel of the violence which he had also lived through years ago. Soon after, an incident in a movie theatre provided the final impetus:

I was in the cinema watching ‘Cloud Atlas’ – a film about past lives. There is a love story in which the two characters find each other over and over again in different lives. In one, they are mother and son, in another they are two lovers. In yet another life, they are gay lovers, and their end is pretty sad. And the people in the theatre laughed: Oh look, they’re queers’. Laughing. And I just reacted… This thing with Angelo had happened a week before, [and] I have always had a very big mouth, so when I saw a girl laughing beside me, I said, ‘Do you want me to grip a man and kiss him so you can piss yourself laughing? Do you think it’s a joke? I’m not a joke!’

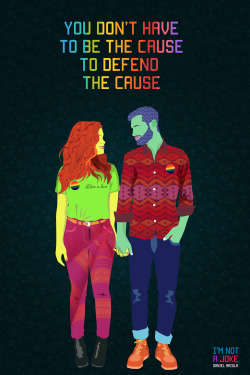

Artwork from the ‘I'm not a joke’ campaign.

Artwork from the ‘I'm not a joke’ campaign.

Experiences of threat and censorship

Arzola’s case demonstrates that censorship is often aided by social structures and their defenders. Efforts to maintain the norm are tied to power, and censorship becomes the work of many.

As ‘I’m not a joke’ spread throughout social networks, boosted by online promotion by celebrities, many other organisations became interested in Arzola’s work:

Neil Gaiman, creator of ‘Coraline’, shared it on Tumblr. And it was like a boom. That made it go viral on Tumblr. Suddenly people were writing me from Russia. People from Portugal wrote me, asking me to do the campaign in Portuguese, so we did it in Portuguese. And since, the campaign has gone viral in 30 countries. The second country where it went viral was Australia. […] The campaign went viral in many places, but in Venezuela the only people who knew about it were activists. Until Madonna retweeted me. When she shared it, there was a ‘boom’. Many people wrote me, including the Dutch organisation that [would eventually help] me out of the country. It was madness.

As Arzola received more attention in the media, his political work grew in scope. He criticised the use of homophobic speech by government figures and the lack of progress on legal equality for LGBT people, despite the support that Chavismo’s leaders promised the LGBT community:

Once they gave me a voice in the media, I started to denounce the things that happen in Venezuela. I started to say that the State uses its force to promote homophobia, that homosexuality might not be illegal but it is not free, that the State says ‘OK, give them a truck for the march, but they cannot speak of equal marriage’. As it happened in March of 2012, as it happened in March of 2013.

With this, a gap opened between the forces supporting the government and the work driven by ‘I’m not a joke’. Increasingly, threats began to take different forms:

I received an invitation to exhibit in a theatre in Caracas. [An exhibition that turned out to be part of a government initiative …] At no point in ‘I’m not a joke’ will you find a sentence against the government. I do not want to tell people what to think. […] This is a moral choice. In the end, I decided be polite to the host, and I stayed. But as the exhibition ended, I left.

However, from that moment I began to receive threats. Calls. One time a guy comes up to me and says “I’m glad you’re here, f**n escuálido [“escuálido” is the name given to government opponents]. I smiled and said “thank you” to avoid conflict. [… The threats continued] in various formats. I have a theory that as times change, fashions change, and dictatorships change. They learn to dress up. The way that our computers are not the same as they were 20 years ago, dictatorships aren’t either. They learn to dress up, to camouflage. I started getting phone calls to my personal phone from private numbers saying ‘Keep talking, faggot’. ‘One queer less, no one will notice.’

In one of the last [threats], they told me ‘You look good walking down the Coromoto (street), alone.’ They told me that if I talked about this, things were going to get worse. … At that time I was living in my mother’s house, so I stopped fueling the fire. I had several friends who had been killed. At that time I remembered that people from the Netherlands, the NGO Radio Netherlands, told me that they were having an event featuring voices that have survived homophobia in countries of conflict. I was told that I would be the representative of Latin America. I told them what was happening to me and began a process of seeking refuge internationally. However, the process required me to return to Venezuela.

People’s power can also censor

Threats are a part of censorship. Government agents were not the only people who wanted to hide the message of ‘I’m not a joke’. However, much of this disruption contains nuances that are difficult to understand or to locate.

Sexual minorities are often highly vulnerable to violence and discrimination. Between May 2013 and May 2015, 47 hate crimes were reported in Venezuela against people who express themselves in a way that is outside the norm. Even these figures give a blurred vision of reality. Activists and advocates for persons belonging to these groups are concerned that the vast majority of such crimes go unpunished, not only because of the inefficiency of institutions, but because victims are afraid to speak up.

One example of this took place at an exhibition of Arzola’s work in Chacao Cultural Centre in Caracas:

It was assumed that [the exhibition] would last five days, but thanks to the receptivity of the people, it was extended 10 more days. During these days, however, certain letters began to arrive to the Cultural Centre saying that my work was ‘unworthy’ and ‘not for children’, that it could not exist in a public space.

Some letters were anonymous. Others were from people who had allegedly entered [the exhibition], and had complained.

All of it was super abstract. No one ever said who had complained. At one point I received a call from the lawyers of the Cultural Centre, and it made me realise that this was more than just gossip. Some people reportedly complained to the Mayor, complaining that the exhibition was pornographic. They failed to close the exhibition, but they took down two posters …

Artwork from the ‘I'm not a joke’ campaign.

Censorship in academia

Since the formalities of seeking refugee status required that Arzola return to Latin America, he chose to wait in Buenos Aires rather than Venezuela to avoid risks. While there, he enrolled in a Masters of Human Rights program. But political pressure did not stay in the Caracas galleries or stop with the anonymous threats. In the courses offered by the degree in Human Rights at the University of La Plata, Arzola encountered severe limitations to debating the issue in Venezuela:

We know that when we talk about human rights in Venezuela, we talk about how the State and its forces violate the human rights of individuals. In [our] classes, Colombians exposed Human Rights violations under ex-president Uribe. Argentines exposed the human rights violations during the military dictatorship. When it was our turn, [the Venezuelans], the teacher said, ‘first you have to send me what you’re going to say in order to review it.’ Why? ‘To be sure of what you’re going to say. This university gave an award to Chavez.’

The rest of the teams were given the whole morning to discuss their cases. The Venezuelans, though, were given only five minutes to present.

We said we would play the game. We organised. In eight minutes we discussed the student protests, the closing of media, the closing of tv channels and radio stations. But before we talked, the professor [told the audience], ‘I have to apologise for what you are going to hear, but you need to know that the next talk is an anti-Chavez talk.’ I said, ‘We are not anti-Chavistas, we are anti-violence. We are in a master’s of Human Rights program.’

All the theses presented by the three Venezuelans on Human Rights abuses in the country were rejected. It is there that you realise the danger of ideologies. You get a master’s degree in Human Rights, but you cannot challenge the violation of Human Rights in a country, because the country is part of a process that you are following. At that time I decided to abandon the Master’s, disappointed.

Artwork from the ‘I'm not a joke’ campaign.

Domino effect

Arzola’s work continues from Chile. The campaigns continue their sharp messages that support many minorities, not just gendered ones, in their struggles against oppression. I’m not a joke is flexible and contributes to other campaigns that promote tolerance, respect for individuality and equality, and the defense of peace and human rights.

The initiative created by Arzola now has numerous awards and is internationally recognised and promoted by various groups that advocate for human rights and LGBT communities. The answer to a ‘joke’ in a small cinema in Maracay created a domino effect that continues to expand.

The focus, however, remains the defense of the dignity of people who step outside of the generic norm, who refuse to be objectified, or to be part of dehumanising stereotypes. It is followed by those who, despite not being a part of the cause, defend it, and those who refuse to be silenced by government or private oppression. As a result, an increasing number of people take part in groups and communities that challenge the norm, and that, far from being a joke, is today a community of great strength that carries out advances which will benefit not only their groups, but society as a whole.

See more artwork on the No soy tu chiste Tumblr page and the No soy tu chiste Facebook page.