Image of the documentary “Antonieta” (2015). Published with permission, Magnólia Produções

Antonieta de Barros was a young girl when she wandered around her mother's boarding house trying to learn the letters of the alphabet. Sneaking among the students, she as well as her sister Leonor learned to read and write little by little. Antonieta couldn't have imagined that studying the alphabet would set her on a course to become the first black woman legislator in Brazil's history. The year was 1934 and slavery had been abolished less than 50 years prior.

Few people know Antonieta's story or even know who she was. In Florianópolis, the capital of the state of Santa Catarina in southern Brazil, streets, schools and tunnels all bear her name. There is even a memorial dedicated to her. However, like so many other names on street signs, for many she's just an address — something filmmaker Flávia Person decided to change.

Born in São Paulo, Flávia lived in Florianópolis for seven years. She discovered Antonieta while researching the history of black people of Santa Catarina, the Brazilian state with the smallest proportion of that population: only 15% of the catarinenses declare themselves black or part black. In the elections of 2014, it was the only state that didn't elect a black person. Still, it was there where 82 years before, a black woman took office after being elected through popular vote.

Flávia became fascinated, as she told Global Voices:

Fazer um filme sobre a Antonieta me pareceu urgente. Depois que descobri que ela foi professora, diretora do instituto de educação, cronista dos jornais mais importantes do estado, a primeira mulher a ser eleita deputada em SC e primeira negra no Brasil, e mesmo assim, nem os nativos de Florianópolis conhecem bem a história dela, pensei que era o momento de fazer um filme e propagar a história dela para o máximo de pessoas possível.

A film about Antonieta seemed urgent to me. After I found out she was a teacher, director of an educational institute, columnist of one the most important newspapers in the state, the first woman to be elected in Santa Catarina and the first black woman to be elected in Brazil, and still, not even Florianópolis natives know much about her, I thought it was the moment to make a movie and spread her story to as many people as possible.

Her short documentary premiered in October, after a year of research. To make “Antonieta”, Flávia searched academic dissertations and public archives, but she was saved by the personal files, with never before seen images, of a relative of Antonieta.

Signed, Maria ‘of the Island’

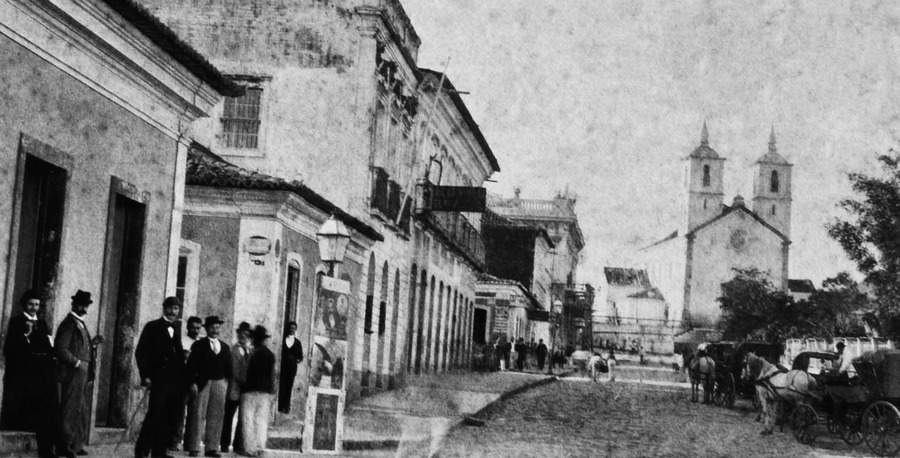

Florianópolis, capital of the state of Santa Catarina, at the time of Antonieta's childhood. Published with permission, Magnólia Produções/Treatment by Yannet Briggiler

Antonieta's mother, a freed slave, became a widow early on and supported her daughters on her own by working as a washerwoman. Catarina always considered education the most precious legacy she could leave her girls. She ended up raising two teachers. At 21, Antonieta had already founded her own school, the “Antonieta de Barros Tutoring Course”, dedicated to teach illiterate, poor adults. For her, “illiteracy is what keeps people from being people“. Flávia adds:

Antonieta fez da educação sua luta de vida. Ela acreditava na educação como único caminho possível para a emancipação feminina e dos pobres. Ela sempre defendeu a educação para todos, independente de raça, credo ou sexo.

Antonieta made education her life struggle. She believed in education as the only possible way for the emancipation of poor people and women. She always advocated education for all, regardless of race, faith or sex.

Writing was another means though which Antonieta carved out a space for herself. As journalist Ângela Bastos noted in a profile of Antonieta published in 2013, she wrote a column under the alias Maria da Ilha (Maria “of the Island”), defending women's civil rights — at a time when almost nobody did in Brazil, especially outside of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo:

A sensibilidade de Maria da Ilha derramava-se em textos variados sobre educação, civilidade, religiosidade, virtudes morais, éticas e cívicas. Abordava também questões relacionadas às relações de gênero e à vida política e social dos anos 30, no Brasil e no mundo.

Maria da Ilha's sensitivity spilled into different texts about education, civility, religiosity, and moral, ethical and civic virtues. She would also tackle issues of gender relations and the political and social life of the 1930s in Brazil and the world.

Brazilian women were officially granted the right to vote only in 1932. Two years later, Antonieta, who had held high-up positions and debated with men and intellectuals as equals, would become one of the first women elected as a legislator, winning a seat in the state's assembly (in that same year, the doctor Carlota Pereira de Queiroz, who was white, was elected federal deputy for the state of São Paulo).

Antonieta knew that the marginalization of women in the political world “didn't represent a natural fact”, but she also knew this happened in other spaces too. As Flávia explains it:

A Antonieta sempre teve um viés político. Logo que se formou, ela fez parte da Liga do Magistério, entidade que defendia os direitos das professoras. Eu descobri que, até meados da década de 30, as professoras do ensino público eram proibidas de contratar casamento, havia uma lei que impedia. A justificativa era que as crianças poderiam fazer indagações indevidas sobre a sexualidade das professoras.

Antonieta was always politically active. After she graduated, she was part of the Teaching League, an organization that defended female teachers’ rights. I found out that, until the mid 1930s, female teachers in public schools were forbidden to marry, there was a law that banned them from doing so. The justification was that the children could ask inappropriate questions about their teachers’ sexuality.

A modern lawmaker

Antonieta with a group of politicians and intellectuals from her time. Published with permission, Magnólia Produções/Treatment by Yannet Briggiler

Antonieta made it into politics with the help of Nereu Ramos from the Liberal Party of the Santa Catarina, who would be become the 20th president of Brazil. Her mother had worked at his father's house, Vidal Ramos, who was also a politician, and had a good relationship with the family. Flávia explains:

O partido, sentindo a mudança de pensamento da década de 30 e querendo imprimir uma ideia moderna, viu na Antonieta, já muito respeitada pela elite por causa de seu trabalho na educação, uma oportunidade. Com certeza, ela deve ter enfrentado preconceito tanto pela cor quanto pelo gênero. Na década de 30, ainda havia discussões sobre a pré-disposição biológica da mulher que a impediria de assumir cargos públicos. Na época, apenas o trabalho de professora e outros relacionados à vida doméstica eram aceitos socialmente.

The party, sensing that society was changing in the 1930s, and wanting to display an image of modernity, saw an opportunity in Antonieta, already very respected by the elite because of her work in education. Certainly she must have suffered discrimination because of her skin color and because of her gender. In the 1930s, there were still discussions about women's biological pre-dispositions, which would make them incapable of taking public office positions. At that time, only the work as a teacher and others related to domestic life were socially accepted.

The school created by Antonieta continued operating for almost 10 years after her death. And the discussions initiated by her in the state assembly are still relevant. For Flávia Person, this shows how history often forgets women, even when they're protagonists.

The name of the first black deputy lives on in other ways too. In Santa Catarina, a group of black female teachers debate education, equality and public policy in a blog called “Other Antonietas“. This year, the federal government's Department of Promotion of Public Policies for Racial Equality launched the Antonieta de Barros award for young and prominent black communicators .

When asked what Antonieta would think of today's Brazil, where governors fight students who ask for more schools, women are still a minority in politics and have their rights threatened in Congress, but where also the gender discussion is blossoming, Flávia replies.

Certamente ela também estaria gritando “Fora Cunha”.

For sure she would also be shouting Fora Cunha [“Cunha, out”; Eduardo Cunha is the president of the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of Brazil's Congress]

For more information about the documentary “Antonieta”, check out the film's official page (in Portuguese).

1 comment