Image edited by Kevin Rothrock.

This article is part of a larger guidebook by RuNet Echo to help people learn how to conduct open-source research on the Russian Internet. Explore the complete guidebook [1] at the special project page.

With most photographs and videos, the most reliable way to conduct verification is through satellite images, allowing you to geolocate content by matching it to a known location. Sometimes, this requires observing changes in an area over time. Satellites have photographed almost every inch of the Earth, but there are special considerations when working in Russia and Ukraine concerning the availability of satellites and street-level imagery. This guide will provide instruction on using satellite images, with a focus on historical imagery, and available street-level imagery accessible for Russian and Ukrainian cities.

Contents

- 1 Google [2]

- 2 Yandex [3]

- 3 Wikimapia [4]

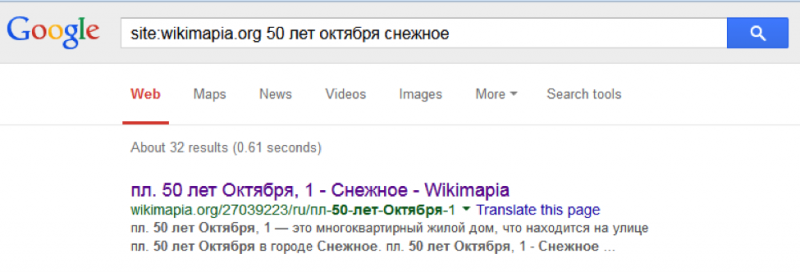

Likely the most useful single piece of software when conducting open-source geolocation research is Google Earth Pro, which can be downloaded for free here [5]. Google purchases its satellite imagery from Digital Globe, a private company with numerous satellites in orbit.

Google Earth—which is a downloadable program—is not the same as Google Maps—which is what you access through your mobile apps or on a Web browser at http://maps.google.com [6]. While Google Earth contains many of the same features as the more familiar Google Maps, Google Earth also provides easily accessible historical imagery, 3D terrain mapping, customizable locations, and markers that can be quickly imported and exported, as well as many other features. In short, Google Earth is geared towards the power user, while Google Maps is for more casual use.

Countless open-source reports use historical imagery comparisons in their analysis, but one recent example of this process can be found in a March 2015 Bellingcat report [7] (note: this text's author, Aric Toler, also wrote the Bellingcat report) that analyzed a large Russian training camp near the Ukrainian border. Viewing the location of this training camp, just south of the village of Chkalova in the Rostov oblast, reveals an extremely large, well-travelled training camp.

A question immediately comes to mind: is this training camp new, or has it been around for years, without any correlation to the Ukrainian crisis? Scrolling through the historical imagery on Google Earth will quickly reveal this answer.

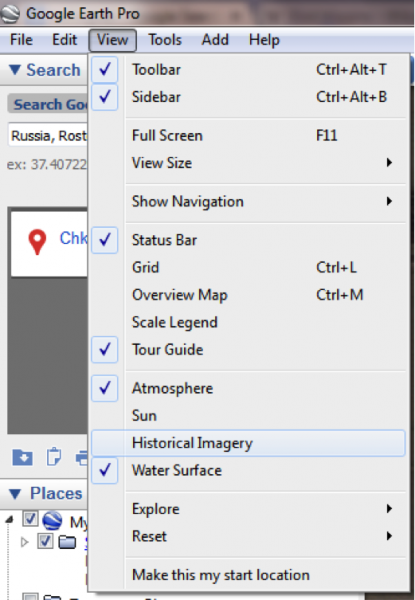

After choosing the “Historical Imagery” option under View, a slider will appear in the top-left corner of your satellite imagery. After rolling back the imagery to a previous date, we see that this training ground was pristine farmland in October 2013—revealing that the camp sprung up anew after the Ukrainian crisis began.

Yandex

The Russian search engine Yandex operates a mapping service [11] similar to Google Maps, including road maps, satellite imagery, and selective coverage of street-level imagery.

There are two ways to access Yandex maps—through maps.yandex.ru and through maps.yandex.com. As you'd expect, the latter is in English, and the former in Russian. They are largely the same, but the layouts are slightly different.

The top version is the English site, and the bottom is Russian. For the remainder of this tutorial, the Russian version (bottom) will be used, but the English version is roughly equivalent and the instructions should mostly translate over.

Instead of “street view,” Yandex uses what it calls the “Panorama” view for street-level imagery of certain cities in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan (Astana, Almaty, and Karaganda), and Turkey. As evident in the map below, only fairly large cities and roadways have Panorama imagery available, indicated by the shaded blue areas. You can turn on Panorama imagery by clicking the Panorama (Панорамы) button in the top-right of the page.

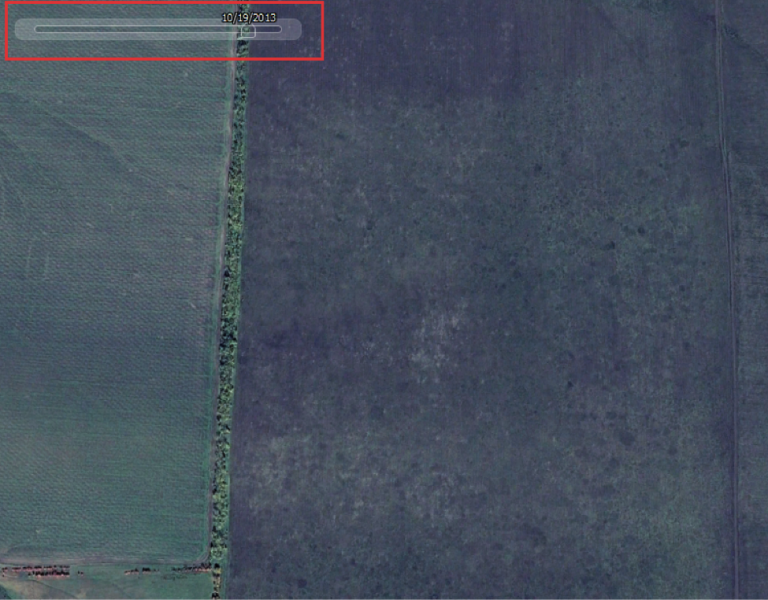

A very nifty feature that is not available on Google is livestream videos from locations (most often traffic cameras). After selecting the video-camera option in the top-right corner (Видеокамеры), you can select the purple camera icons on the map (most often in densely populated urban areas) for a livestream of the location. See below with a traffic camera in central Moscow:

Like Google Maps, Yandex can place geolocated photos from users onto their maps, giving you additional views of a location from the ground.

In the above screenshot, the title of the photograph (which is “Untitled,” без названия) is available, along with the user responsible for uploading the image (bottom-left red box), and the date of the photograph’s upload (bottom-right red box). Turn on the photographs overlaid on the map by selecting Photographs (фотографии) in the top-right corner.

The Yandex satellite imagery, which is unique from the Google Maps (DigitalGlobe) satellite imagery, can also be accessed through Wikimapia [16].

Wikimapia

Wikimapia [16] combines an array of satellite services with user-inputted descriptions of locations, providing an impressive array of professional (satellite) and local (descriptions) information.

[17]The available satellite imagery can be viewed in the top-right corner, including Google (DigitalGlobe) imagery, Google Terrain, Bing, Yandex, Here, OSM (Open Street Map), and Yahoo.

[17]The available satellite imagery can be viewed in the top-right corner, including Google (DigitalGlobe) imagery, Google Terrain, Bing, Yandex, Here, OSM (Open Street Map), and Yahoo.

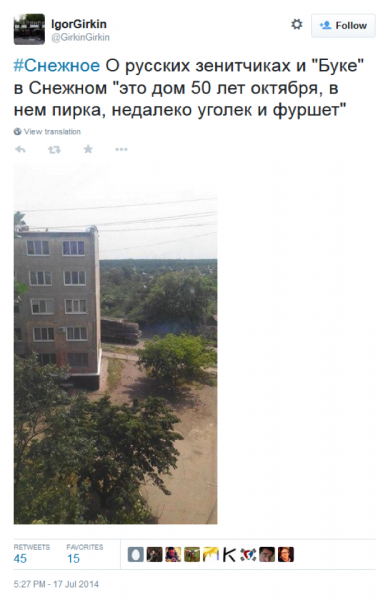

This tweet [18] was posted a few hours before the MH17 disaster, showing a Buk anti-aircraft system supposedly in the town of Snezhnoe. By using Wikimapia, we can locate some of the landmarks mentioned in the tweet and verify the location of the image.

The five locations mentioned in the tweet above are reproduced below with English translations:

The five locations mentioned in the tweet above are reproduced below with English translations:

- в Снежном: in Snezhnoe

- дом 50 лет октября: house/building 50 Years of October

- в нем пирка: in it is pirka

- уголек: ugolek (small piece of coal)

- фуршет: furshet (buffet, smorgasbord)

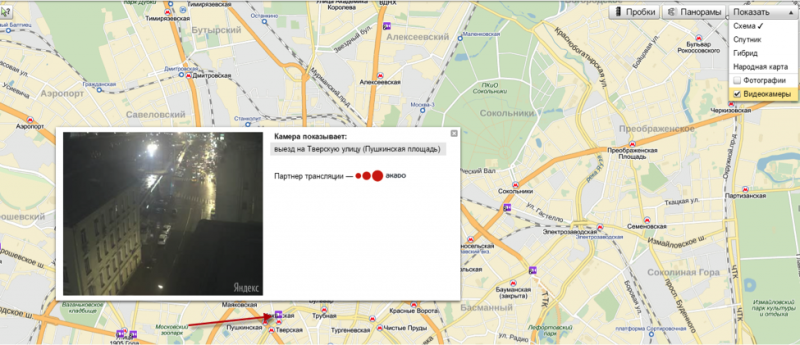

We can assume that the person posting this is not saying that the Buk is near a buffet of food or a little piece of coal, so we need to do some more digging to find the context of the words. The search function within Wikimapia is not very useful, so it is often better to search the site using Google, but restricting our results to those on Wikimapia by using the “site: search” function.

By following the first result, we find that “50 Years of October” is a street in the center of Snezhnoe. From Wikimapia, we can search the nearby location and look for the other landmarks mentioned in the tweet: Ugolek, Firshet, and Pirka.

Two of these are immediately clear on both sides of 50 Years of October (the street that runs vertical between the two landmarks). After clicking their entries on Wikimapia, we find that Furshet is a supermarket and Ugolek is a restaurant.

We do not know where Pirka is (though if you looked long and hard enough, you would see it is a shop in one of the apartment buildings in the area), but identifying four of the five landmarks—the city, street, and two locations—is enough to focus our search on this area for traces of the Buk in the photograph. From here, it's a matter of geolocation and matching angles, trees, and the road in the photograph.

For those wondering: the Buk was indeed in Snezhnoe, photographed approximately 3-4 hours before MH17 was shot down. The photograph was traced back a building on 50 Years of October, facing towards the apartment building on Karapetyana 13a.

***

Whatever a photograph's location, there are always geolocation options—whether it's a livestream from the street, or a blurry satellite photo from 2012. Using the resources described in this guide, you should be able to find the most accurate and helpful image available for locations in Russia and Ukraine, whether it's from Google, Yandex, Wikimapia, or sites less useful for Russia and Ukraine, such as TerraServer [22] or Bing Maps [23].