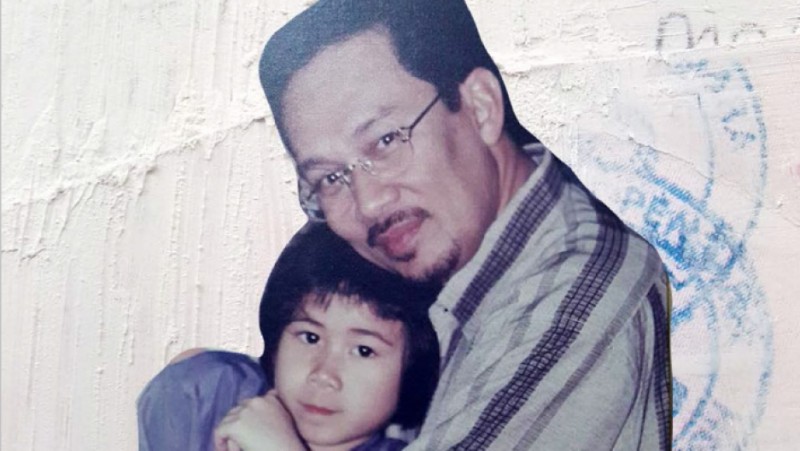

Anwar Ibrahim and daughter Nurul Hana Anwar on the cover of “My Dear Papa.” Credit: Courtesy of Nurul Hana Anwar

This article by Sarah Ngu [1] for The World [2] originally appeared on PRI.org [3] on November 25, 2015. It is republished on Global Voices in two parts with permission.

In this first part, we introduce you to Nurul Hana Anwar, newly published author and daughter of Malaysian political prisoner Anwar Ibrahim. In part two [4], she explains how she came to publish her deeply personal book Sayang Buat Papa (My Dear Papa).

A little girl is crouched down under a table, her head raised questioningly. Her eyes and mouth look afraid. She asks, “Mom, what is going on?”

It is Sept, 20, 1998. The police have just broken into the house. Her father has been taken. Outside, crowds are milling around, yelling Malaysia’s slogan for reform, “Reformasi!”

Her family tells her that a wicked man — the prime minister — is responsible for whisking her papa to prison. Her mother tells her to pray, to trust in Allah.

The little girl, the youngest of five children, is not told that her father was on the verge of becoming the prime minister, and that now he is the nation’s most famous political prisoner, charged with the crime of sodomy. How does one explain “sodomy” to a 6-year-old child?

Read this post in Malay on PRI.org: Penantian Panjang Kepulangan Seorang Bapa [5]

Anwar Ibrahim is a household name in Malaysia. He enjoyed a meteoric rise to power in the 1990s; TIME hailed him on its cover [6] as “the star of a rising generation of leaders” in Asia for his financial reforms and aspirations for democratic reform. He was next in line to succeed his mentor, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed, until he had a falling out with Dr. Mahathir over the state’s patronage system. When he was fired on Sept, 2, 1998, Anwar led tens upon thousands of people in political rallies, calling for Dr. Mahathir’s removal and chanting “reformasi!”The girl’s name is Nurul Hana Anwar. Because Malay custom holds that the child’s last name is the first name of the father, her name essentially reads: Nurul Hana, child of Anwar.

Then Dr. Mahathir made his move and had him arrested. For many Malaysians, Anwar’s arrest was the moment of their political awakening; it was the catalyst of Malaysia’s reformasi movement. That night, they realized that if their government could turn on someone as powerful as Anwar, it could turn on anyone.

Nurul Hana did not know about virtually any of this when the men with ski masks and guns broke into her home. For her, it was simply the day that she lost her papa — the day that, according to her mother, she started hiding under tables more frequently, withdrawing into herself and largely ceasing to speak.

An excerpt from “My Dear Papa” featuring images of Anwar Ibrahim's black eye. Credit: Courtesy of Nurul Hana Anwar

If Nurul Hana lost her voice at age 6, she has started to regain it at age 23. This past August, she gave a speech in the nation’s capital in order to launch her book, Sayang Buat Papa (My Dear Papa). It is a collage of visual images that tell the story of what it feels like, from the eyes of a child, to have your papa disappear at the hands of “bad men,” and then reappear nine days later in a tiny cell with a black eye.

Anwar is not a politician in this book. He is a papa, a husband — he is a man. The book has sold well, reaching fifth on Borders’ nonfiction bestseller list in Malaysia; it was launched [7] in the United States last month.

Nurul Hana did not plan on becoming an author. The book came out of a collage project that she made for class. We met on a Friday morning during the first week of school in September.

Soft-spoken and friendly, she wears wide, round glasses that sit on top of her full cheeks. We were at a coffee shop, but she doesn’t drink coffee, as she prefers hot chocolate, which she likes to sip as she listens to Radiohead and works on a graphic design project for school.

She had just come back from her book launch in which she spoke to an audience of 150 people, which included many prominent politicians, reporters and leaders. Public speaking terrifies her — she once took acting classes in order to confront her fear — but her talk went well, she said. Still, when she met with a reporter afterward, she asked him to not bring a recorder. She did allow me to record our conversation, but her nervousness was apparent in her frequent apologies and self-conscious smiles. Her body, it seemed, was still getting used to her newfound voice.

The timing of her book is not random. This past February, Anwar was imprisoned for five years yet again on the charge of sodomy, a conviction that the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has called [8] “politically motivated.”

Many believed he, given his liberal reformist beliefs and devout Muslim faith, was on the verge of uniting the factious Malay Muslims (majority of population), Chinese and Indian ethnicities in order to overturn the dominant coalition. His imprisonment is a significant setback for the political opposition, but some are openly wondering [9] whether they should stop waiting for Anwar and look toward a younger generation of leaders to take the helm.

Nurul Hana’s book does not really care about any of these conversations. It is expressly apolitical, determined to show a different side of Anwar. One of the most repeated images in the book are the photographs of her papa’s feet, covered only by a pair of slippers. When I asked her why she chose his feet, out of all things, to display, she responded by saying most people only know her papa from images or clips of him standing at a podium, giving a speech.

By repeatedly showing his plain feet, which could be mistaken for any other human’s feet, she is revealing Anwar stripped of the trappings of power. When the government imprisoned Anwar, they did not just take away his political career, his job and his reputation. They also took away a grandfather, a father and a husband. In Nurul Hana’s words, “they took everything,” including his body.

If the opposition should move on without their political savior, then the movement to release Anwar will have to rely on less on his political prowess, and more on the basic argument that no human ought to suffer such injustice at the hands of the State. Anwar’s basic humanity will have to be what is at stake — which is why his youngest daughter’s art book might prove more politically relevant, prescient and hopeful than expected.