![USS Litchfield (DD-336) at Smyrna on 13 September 1922: The ship helped evacuate refugees from the fire that started raging that day. Image by International Newsreel [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://globalvoicesonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/USS_Litchfield_at_Smyrna-e1442167084332.jpg)

USS Litchfield (DD-336) at Smyrna on 13 September, 1922: The ship helped evacuate refugees from the fire that started raging that day. Image by International Newsreel [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The Great Fire occurred four days after the Turkish forces entered into Izmir on 9 September 1922, effectively ending the Greco-Turkish War in the field. The subsequent fire completely destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city, with various historical accounts still debating who exactly was responsible for the fire. Greek and Armenian refugees crammed the waterfront trying to escape from the fire, while Turkish troops and irregulars committed massacres against them.

The Asia Minor Expedition and Catastrophe, as well as the ethnic cleansing of the Greek population living there for thousands of years, had an enormous impact on the Greek psyche. The Smyrna Catastrophe (the term Greeks generally use to refer to the massacre and the fire) is considered the worst incident in modern Greek history, and the plight of the refugees halted the Greco-Turkish relations for many decades. For the Turks, it's known as the Kurtuluş Savaşı, the War of Independence.

The Greek Genocide Resource Center, aiming to raise awareness of the extermination of Greeks in the Ottoman Empire during 1914-1923, tweeted the following famous video capturing the fire:

Kemal's ultimate triumph: the burning of Smyrna (#Izmir) to ashes https://t.co/O3U3ben8pz

— Greek Genocide RCen (@greek_genocide) September 11, 2015

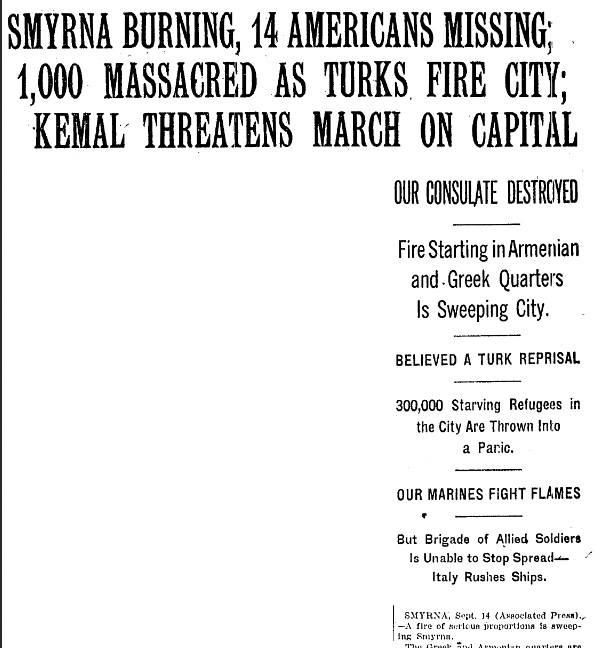

The New York Times, at the time of the incident in 1922, had reported:

Excerpt from the NYT, Sep 15, 1922. Screenshot from New York Times archive

News and lifestyle portal LiFO marked the day with a special coverage section in Greek of the Smyrna Catastrophe, which it described as causing “the biggest migration wave in Greek history.”

Thousands of refugees fled mainly to Greece, trying to start a new life amidst prejudice, insults, and harsh living conditions, as reported in personal testimonies of the refugees’ family members:

Η μητέρα μου, ο πατέρας μου, ο παππούς μου, η γιαγιά μου ήρθαν κυνηγημένοι από τη Μικρά Ασία. Έφυγαν κουρασμένοι και ταλαιπωρημένοι. Άφησαν τα καλά τους, τις περιουσίες τους. Η μητέρα μου ήταν νιόπαντρη και ήρθε με μία σακούλα ρούχα. Όλος ο κόσμος τους κυνηγούσε. Τους αντιπαθούσαν και τους αποκαλούσαν τουρκόσπορους. Πίστευαν πως θα τους πάρουν τις περιουσίες. Τους έδωσαν έναν συνοικισμό όπου έμειναν 80 οικογένειες. Πάμφτωχες. Επειδή όμως ήταν εργατικοί, τακτοποιήθηκαν όλοι. Όσοι είχαν έρθει από τη Μικρά Ασία, ήταν καλοί άνθρωποι. Αξιοπρεπείς. Στην Ελλάδα δεν τους χώνεψαν. Η Μικρά Ασία ήταν ο πολιτισμός της Ελλάδας, αλλά τους κυνήγησαν”, θυμάται.

My mother, my father, and my grandparents arrived in Greece, hunted from Asia Minor. They left tired and shagged. They left their fortune behind, all their goods. My mother was newlywed and came with just a bag of clothes. Everybody [in Greece] chased them. They disliked them and called them tourkosporoi [“Turkish offspring”, considered a slur]. People believed [refugees] were going to steal their property. The refugees were given a small camp for 80 families. Dirt-poor. But they were hard-working people, so they all settled. Whoever came from Asia Minor, he was a good person. Decent. In Greece, they didn't like them. Asia Minor was Greece's civilization, but they hunted them.

Η πυκνότητα του πληθυσμού την περίοδο 1922-23 είναι πολύ μεγάλη και οι αρμόδιες υπηρεσίες ανεπαρκείς. Έτσι, αρχίζουν να καταγράφονται τα πρώτα κρούσματα τύφου, ιλαράς, οστρακιάς, μηνιγγίτιδας, ευλογιάς, δυσεντερίας και χολέρας. Η Αθήνα και ο Πειραιάς αλλάζουν πρόσωπο. Στις 15 Νοεμβρίου η εφημερίδα «Πρωτεύουσα» σημειώνει: «Οι δύο Δήμοι, που δεν εγνώρισαν ποτέ την υγιεινήν, δεν έχουν επαρκές νερό και τα δημοτικά λουτρά είναι άγνωστα. Οι δύο πόλεις είναι κτισμέναι επί μυριάδων βόθρων, οι οποίοι έχουν υπερπληρωθή. Τα ακάθαρτα νερά ρέουν εις τους δρόμους […] Ουδέποτε άλλοτε η ζωή της Αθήνας έγινε δυσκολωτέρα και η υγεία επισφαλεστέρα. Η φθίσις οργιάζει παραπλεύρως των άλλων ανθρωποκτόνων νόσων. Τι πρέπει να κάμωμεν; […]»

Population density during the years 1922-23 was very high and the responsible state services were inadequate. Soon, there were incidents of typhus, measles, scarlet fever, meningitis, smallpox, dysentery and cholera. Athens’ and Piraeus's faces changed. On November 15th, the newspaper Protevousa [“Capital”] noted: “The two Municipalities, never familiar with hygiene, don't have adequate water and public baths are non-existent. The two cities are built on top of thousands of overflowing cesspits. Sewage waters flow in the streets […] Never before has life in Athens been more difficult and health more endangered. Tuberculosis is rampant, along with other killing diseases. What should we do? […]”

Greek refugees from Asia Minor in the 1920s stay in the galleries of Athens’ Municipal Theatre. On each balcony, a family.

Refugees from Anatolia went as far as Middle-Eastern countries, in order to save their lives. It seems that migration routes remained the same throughout the centuries, regardless of whether their direction was eastbound or westbound.

Greek refugees in Aleppo, Syria. Source: Library of Congress.

Greece has a unique way of “forgetting” its past. The rise of far-right movements and racist hate speech and behavior has been quite visible during the last several years.

This anti-racist and pro-refugee motto has been widely seen as graffiti on the walls in Athens and other Greek cities:

“Our grandfathers [were] refugees.

Our parents [were] immigrants.

[Are] we racists?”

Widely spread graffiti on the walls of Athens.

Έλληνα θυμήσου… pic.twitter.com/0N542Tit2a

— Alexandros Tziolis (@alex_tziolis) September 11, 2015

Greek man, remember… [picture reads: Smyrna 1922, Syria 2015] pic.twitter.com/0N542Tit2a

Μου έλεγε η γιαγιά μου η Σμυρνιά οτι κρατούσε το χέρι του αδερφού της το '22 τρία μερόνυχτα μέχρι που μελάνιασε pic.twitter.com/zhMn9EcY32

— ☤ Fotios Daglis ☭ (@FotiosDaglis) August 24, 2015

My grandmother from Smyrna told me that she was holding her brother's hand for 3 nights back in 1922, till it got bruised.

3 comments