Kaya Highway is a “rough road” running through Morobo from the Ugandan border to Yei. South Sudan, the size of France, has about 110 kilometres of tarmac in Juba, the capital, and only one tarmac road of 120 kilometres connecting the capital to the Ugandan border. Some parts of South Sudan become inaccessible during the rainy season. Photo: Pernille Bærendtsen.

One Saturday afternoon in August, I’m sitting with a colleague on the bank of the River Nile in Juba. The sight of the ancient river is tranquilizing. It leaves me with the impression that the river has chosen to ignore all the disturbances surrounding it to pursue its rapid, single-minded flow.

Some distance away to my right a man is about to break a wrecked ship into pieces. He sets the dry grass that has grown up through it on fire. The wind picks up. Black bits of soot rise in the air, blends with the red dust and settles on our white tablecloth.

Here, everything can change within a minute.

We are the khawadiya—the strangers—and we try hard to understand how this place works. We exhaust newspapers for information, conversations for meaning and negotiations for hints of peace. In the meantime, South Sudan exhausts its people beyond capacity.

The River Nile flows north through South Sudan. Photo: Pernille Bærendtsen.

Cars cross the border from Uganda loaded to the brim with human beings and cargo. Their iron bellies score the red earth’s unforgiving surface, which strikes back by wearing them thinner and thinner. We note the creased metal wrecks along Kaya Highway up to Yei.

According to the World Bank, about 38% of South Sudan’s population has to walk more than 30 minutes to collect drinking water. Women and girls fill tubs and jerry cans several times a day, until one day the plastic fractures—some will be stitched back to life, scars now exposed for the whole world to see that they once reached an inevitable breaking point. Kitchenware emerges scratched and bruised by a lifetime of harsh use and too many washings with cold, greasy water.

South Sudan is hard work. People clash and crash. Grow threadbare. Nevertheless, people move forward.

About South Sudan

The Republic of South Sudan became Africa’s 55th—and the world’s newest—country on July 9, 2011, following a peaceful secession from Sudan through a referendum in January 2011.

Conflict broke out in December 2013, and the country's development of faced a severe setback. The current hope is that the recently signed Compromise Peace Agreement will lead to greater stability.

NORMAL LIFE

Time is abundant in rural South Sudan. In fact, it appears as if time manages us. We get our breaking news by going down to the Kaya Highway and talking to passers-by. Newspapers are rare and usually days or weeks old. There is no TV, and the Internet is mainly accessible only to the few who work with NGOs. When it rains too long “the Internet sleeps”. The stuff our conversations is made of cannot be Googled.

Three of the staff at the compound where I am staying are pulling up groundnuts. We make small talk as the sun sets. One man explains how he, as a child, happened to shoot another child in the elbow:

“We used the AK-47s as pillows, because we had to be ready if somebody came to steal the cattle we were sent into the bush to look after. I just pulled the trigger by impulse.”

The wounded boy was taken to the elders. Then to the clinic. A walk of many miles in the dark bush. He survived.

“Do you think South Sudan maybe is the worst country in the world?” asks another after his colleague has finished the story.

My heart sinks. He notes my apprehension, and concludes: “I think Somalia is worse.”

Many people have similar stories to tell, of life in war and life in peace. In between is the “normal”. It pops up as we discuss the planning of radio programmes.

“Let us just have normal life,” our editor at the radio says.

“What's normal?”

“Normal is when food prices are not too high. It is when you don't have to dig deep into your pockets. It is when you don't have to deal with insecurity,” she explains.

We talk about the importance of neighbors. “You cannot live without them. One day you have no cassava flour, and they will give you, or say, ‘take those greens in my little garden for your sauce.'”

A family in Morobo. The majority of the South Sudanese population resides in rural areas. Photo: Pernille Bærendtsen

DEMANDS FOR PEACE

Things have only ever been “normal” for relatively short periods in the history of South Sudan. But there are pockets of peace, and people who draw on incredible personal reserves as they push forward.

On August 27, South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir signed his part of a long awaited agreement on peace. The Compromise Peace Agreement, as it is called, comes, nevertheless, with many reservations. It is an agreement designed by people who know much more of war than of peace, and could be regarded more as an agreement on “non-war” than on peace.

On an early Saturday morning in late July, as I drive into the town of Yei, I encounter a protest, a group of women carrying signs demanding peace and co-existence: “We are mothers. We need peace.” Suddenly humbled, I stop the car. From the side of the street I watch the women pass.

Later, I meet with the people at the Centre for Development and Democracy, who have taken an active role in preparing these women for this protest. Back in 2005-2007 I worked with their “sister-centres” on the other side of the border in Uganda. We worked on the premise that if you provided South Sudanese youth with books they would complete their educations and one day return to rebuild South Sudan. “You can bomb schools,” we used to say. “But you can never take education away from the people”.

When I returned to South Sudan in 2013, 2014—and now again in 2015—and I'd meet a South Sudanese born in the 1980s, I'd ask: “Where did you go to secondary school?” I’m astounded by the number I meet who completed secondary school by studying in these resource centres.

The people at the centre in Yei have now shifted towards taking an active role in civil society building. This makes a significant difference in the current situation in South Sudan, where media and freedom of expression suffer badly. During the weeks leading up to the negotiation of the peace agreement, the Centre hosted meetings and talks on the agreement’s content. They also educate citizens on legislation, duties and obligations. It takes extra energy to keep addressing agendas where you might be met with resistance.

We sit under the big mango tree dubbed the “tree of wisdom”, and share stories of former Danish development workers, of mutual friends. “You know, they stayed with us for a long time, so we learnt from them.”

The time factor is essential. Sound development does not create results overnight—it take years and years. Here in South Sudan I have encountered what in other places would be a simple problem, only for it to morph into something far more complicated. Few khawadiya, myself included, can devote the time it really takes. It is too easy to compare South Sudan to other African countries and point at the hardship, the madness and the shortcomings. It is too easy to excuse ourselves, and say this money could be better spent somewhere else. Patience and understanding might be the most difficult thing for us to give, but it is often what makes most sense.

A student in the library at Centre for Development and Democracy in Yei. According to the World Bank, only 27% of the population aged 15 years and above is literate. The literacy rate for males is 40%, and 16% for females.

Photo: Pernille Bærendtsen

24-HOUR MEDIA BLACKOUT

The media and civil society have always experienced tough times in Sudan and South Sudan, but the conflict in 2013 has made working in the media even more dangerous. Journalists explain that they receive threats, often from a person calling from an unknown number to tell you to stop writing, for example, on Facebook.

On the night of August 19, Moi Peter Julius, a young journalist, was killed. Shot in the back with a pistol at close range by an “unknown gunman.” The killing took place shortly after President Salva Kiir threatened to kill journalists for reporting “against the country.” A few days later, the presidential spokesperson withdrew the statement, saying that Kiir did not mean it “that way.”

I meet with some journalists in Juba the night of the August 20. The following morning they decide to honor the murdered journalist with a 24-hour media blackout.

Several newspapers have closed down. One of the most popular English-language papers, The Citizen, was closed in early August and had to lay off staff.

Besides direct threats, journalists, like everyone else, have to deal with the rigors of life in an increasingly intense and unstable political environment. In Juba you can be pulled over at any time and intimidated by men carrying big guns. Politicians, activists and journalists disappear. “Unknown gunmen” remain unknown. It is a daily struggle made up of self-censorship, financial hardship and existential doubts about one’s own sanity and intellectual future. Then there are the journalists who toe the line. The media landscape is complicated. The lack of free media is going to hurt South Sudan not just in the near term, but also in the future.

DISPLACED MEMORIES

On the last Saturday in August I receive an invitation to join a poetry salon. It takes place on the outskirts of Juba, at the foot of the Jebel Kujur mountain in the home of Lawrence Korbandy Kodis, former chairperson of the South Sudan Human Rights Commission, now legal advisor to South Sudan’s president. Later the Minister for Education graces us with his company. Also present are Moses Akol, a former ambassador to Sweden, and Jimmy Wongo, former minister in the government of the Central Equatoria State.

These poetry sessions take place bi-monthly, and the group has kept them going for the past eight months. This one starts with questions about how— in a fragmented country, run by people with selective memories—one could use poetry and fiction to stitch together a more complete history.

A talk follows about how to encourage people to write what they know, about their own history, their homeland. When people are displaced by conflict, memories are displaced too. The history of South Sudan is fragmented and full of gaps.

“If you don’t speak out history will be wiped out,” someone says. “The villains will be our history.”

I get a lift back to my hotel with Wongo. He apologizes that there were fewer women than usual. “But you were there,” he says. I am grateful for having been invited in, and as I explain how special this experience has been for me, the car in front of us is being robbed.

We are stopped at a roundabout, awaiting the green light. The car rolls backwards as the driver jumps out to pursue the robber among the waiting cars. I feel the slow rush of panic as I lock the doors of Wongo's car. We are stuck. We cannot escape. All we can do is wait.

Wongo is completely calm. The red light changes to green, and we continue on our way. He talks about the peace agreement and “the window of hope”—that ceasefires might eventually develop into peace.

A girl and her sibling at the market in Yei. South Sudan is a young nation, with two-thirds of the population under the age of 30. Photo: Pernille Bærendtsen.

IT’S NOT YOU—IT’S ME

On August 27 the president finally signed the agreement. What its impact will be, however, is far from clear, and there are no wild celebrations apart from the usual loud crowd in the hotel bar.

“This is a kind of peace, and all kinds of peace are better than war,” says a guy in the bar who “works in oil” and who can down tequila like there's no tomorrow. I smile back.

I was in South Sudan when the war began in December 2013. On the way to the airport as I was being evacuated from Juba, a young SPLA soldier in khaki military uniform and broken Ray-Ban sunglasses waved our car off the road at a makeshift checkpoint. He appeared to be fuelled by a mixture of alcohol and relief that the fighting in Juba had subsided.

He stuck his head through the open window and stared us, the departing expats, in the face. “Come back! Why do you always have to leave?” he said, looking at each of us in turn, seeking reciprocated contact. His eyes met mine as he completed his inspection. “I love you,” he said. “Just go!”

That declaration of love put all my previous break-ups in perspective. I was embarrassed to leave South Sudan this way. The old break-up cliché “it’s not you, it’s me” had never been more fitting.

The resilience of the South Sudanese—their apparent ability to adapt easily to stress and adversity—is what keeps this country going. But it can also be ruthless. South Sudan is not for the faint-hearted. There were many days when South Sudan got the better of me. I have sat back in resignation and felt I would cry at even the slightest injustice. There have been days where I severely doubted the whole concept of South Sudan—doubts which, in the end, were less about the country than about my own capacity to deal with it.

“Why South Sudan?” a colleague asked before I left this time. It is true, but also a bit feeble, to say that South Sudan is unlike any other place. Freedom of expression is under pressure, but I keep finding people who defy it and think in original and innovative ways. People who get up each morning and move forward in spite of the most impossible conditions. In South Sudan, I’ve always found people who long for deeper conversations about the space in between life and death.

To me, South Sudan is all about them.

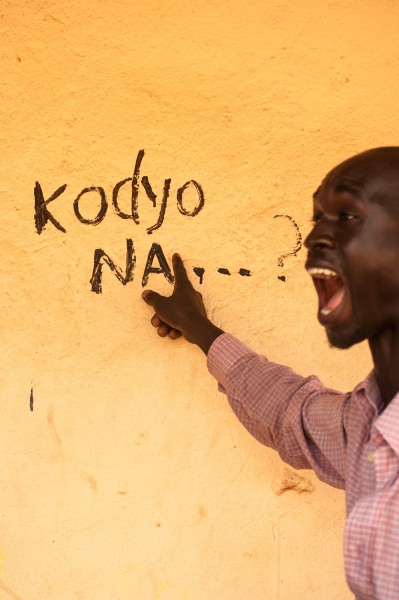

In Kakwa, the local language of the areas of Yei and Morobo, “‘Kodyo na…?’”means “What about me?!’. Photo: Pernille Bærendtsen

Pernille Bærendtsen worked with a community radio station in South Sudan from July to September 2015. She previously worked with South Sudanese refugees in northern Uganda in 2005-2007, and carried out short term assignments in South Sudan in 2013 and 2014.

3 comments

Pernille, thank yo so much for your beautiful writing! In the last four paragraphs you managed to sum up perfectly what it is that makes South Sudan and it’s people so speciale to the khawadiya who has fallen in love with that place ‘unlike any other place’.

I’m one of those… and I do hope that one day I will be able to return…

Thanks Lisa. I appreciate it!