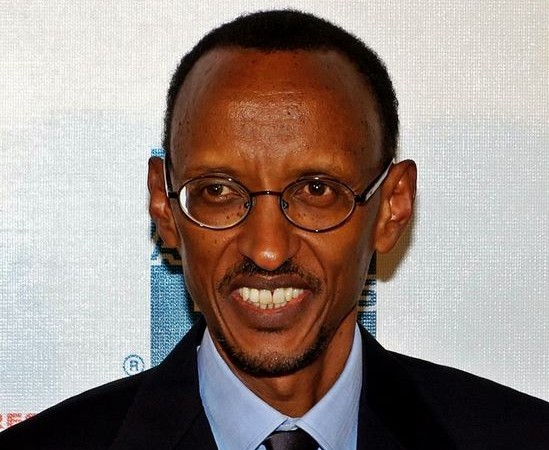

East African Community heads of state in 2009: Yoweri Museveni – Uganda; Mwai Kibaki – Kenya; Paul Kagame – Rwanda, Jakaya Kikwete – Tanzania, Pierre Nkurunziza – Burundi, by Magnus Manske CC-BY-2.0

The constitutions of several Sub-Saharan African countries limit presidents to two consecutive terms. The reason for this position is clear: these constitutions were inspired by western models—more often than not, the French Constitution. By embracing a fundamental law which was born on another continent, in another era and under different circumstances, and by failing to adapting this law to its new local context, you run the risk of its not being ideally suited to local politics.

During the build-up to elections in African countries where political change is predicted, the debate re-emerges almost systematically: should the Constitution be modified so that the state's political leader can set his or her sights on a new mandate?

Today, the question is directed towards Rwanda, the Republic of Congo and even Burundi. It is healthy debate such subjects, but it is also regrettable that this debate emerges only in pre-election periods, when candidates often have an ax to grind and fail to look at the bigger picture, and even make statements that contradict their deepest convictions.

In the Republic of Congo, for example, after having long denounced the current constitution, the opposition now rejects the notion that the Constitution should eventually be changed. The reason for this is that the change in question could see the current president, Sassou Nguesso, setting his sights on a third term in 2016. So the Congolese opposition has found itself once again in the indefensible position of defending a document it has always fought against, and of having to reject outright a new, more democratic constitution than even it had wished for. On the margins of electoral affairs, there would still be subjects leading to deep analysis of the need for mandatory political changeover after two mandates.

The reality of political life and the exercise of power in Africa date back to the frameworks that emerged in the pre-colonial period. The kingdoms and leaderships which widely controlled Africa were governed at the time by hierarchical clan or family principles. Political changeover “African style” is characterized by very specific traditions, under which the candidate running for office must already be a well-known figure who, in short, must already have proven himself before being able to take power. Failing which, he would not be taken seriously.

The strong community ties that prevail in Africa stand in contrast to the relative individualism prevalent in the West that accounts for lightning careers and dazzling success stories. In numerous African countries, a “great man” can only be replaced by another, which explains the popularity of men who, as soon as their governance has been declared legitimate, have held on to political power for a long time. In Europe, on that basis alone and regardless of their track record, they would be called tyrants.

This concept of power, while perhaps appearing somewhat quaint to westerners today, was not always limited to Africans. The constitutions which from which African states have drawn inspiration are all derived from the first global constitution, born in the United States in 1787. This document did not foresee any limitation of presidential terms. As Yann Gwet, the Cameroonian businessman and writer, recalls in the newspaper Jeune Afrique, the Founding Fathers of the United States, in particular Alexander Hamilton, believed that limiting terms in office would encourage behavior that was contrary to the national interest and the stability of the government. According to the Founding Fathers, in a democracy, only sovereign people are entitled to impose limits on the number of presidential terms. That's precisely why we vote.

Although the United States adopted early on the tradition of limiting presidential terms to two, it was because George Washington, tired of governing, decided to withdraw at the end of his second term. But at the time it was still only a tradition, destined to evolve. The proof, much later, was when Franklin Roosevelt strung together a whopping four terms. As Yann Gwet quite rightly wrote, it still stands that if Washington had waited till the end of his third mandate before proclaiming himself too weary to continue, the tradition, and later on the Constitution, might have retained the figure of three terms instead of two.

In 1947, the Republican opposition, who held the majority in two chambers, approved the 22nd Amendment, which expressly limits the number of presidential terms in office to two. This was above all a political decision, motivated by the fear of seeing themselves further excluded from power for more than a decade. In 1944, however, when the Republican party failed to win the election, it was above all because it wasn't able to offer a sufficiently competent candidate who could stand up to Roosevelt. In this context, political changeover would have weakened the country, which was at the time engaged in a global war.

That is what revealed itself to be the major drawback of the principle of political changeover: the quality of the alternatives on offer. A country is in good shape when its successive leaders are of top quality. That's just as crucial in Africa, where colonisers creating states from scratch divided territories without any consideration for pre-existing ethnic groups. States were outlined according to territory and not to nations or peoples. The resulting tensions are often still real, and it appears reckless to compromise the state of fragile stability that exists in certain countries by putting in command either an incompetent or a figure widely unpopular with a certain segment of the population.

Africa is still a vulnerable continent. Multinational companies, foreign investors, religious fundamentalists—these and others are trying to take the lion's share, shamelessly exploiting resources and people. However, in many cases, even if the opposition knows they are not able to put forward a candidate capable of securing the country's best interests against all kinds of speculators, they apply constitutional leverage to push aside presidents who have arrived at the end of their two mandates. Such manoeuvres, more often than not, jeopardise the stability of the state and, in effect, that of the people.

The idea is obviously not to allow Africa's leaders an unlimited number of terms in office, or even less so to establish life-long presidential terms, but instead to adapt the substance of the constitution to the country's specific needs. From the moment political changeover becomes a constitutional obligation, it cannot be regarded as anything but a constraint in countries where there are few leading figures capable of securing the role of head of state.

The real challenge is therefore not, in some strange arbitrary manner, to limit the number of presidential mandates to two throughout Africa, but to guarantee free, transparent and incontestable elections. If the people really don't wish to see their president re-elected a third time, they'll protest via the ballot box—and vice-versa.

2 comments