Image by Kevin Rothrock.

It’s often said that the freedom of the press is severely limited in Russia. While this has seemed to be the case for over a decade, the freedom of Russia’s online media began to suffer more recently, with the start of the government’s Internet crackdown, following Vladimir Putin’s return to the Kremlin in 2012.

In Putin’s third term, small websites have been blocked and larger outlets have been pressured into editorial changes that have watered down the critical news coverage available to many Russian Internet users. Well over a year ago, state censors indefinitely blocked three relatively small oppositionist news websites. These sites remain online today, but they’re technically banned inside Russia.

Russia launched its Internet blacklist in the summer of 2012, at first targeting content like child pornography and information about illegal drugs and suicide. The blacklist has expanded considerably since then, extending to digital piracy, so-called “gay propaganda,” and more.

In terms of political salience, some of the most sensitive content that can be blocked in Russia today is what is considered to be “extremism,” as defined by a law that entered force in February 2014. This legislation, sometimes called the “Lugovoi law” (after its most prominent sponsor), empowers Russia’s Attorney General to ban websites without any judicial oversight, if officials decide that their content qualifies as “extremist” under the law’s rather vague definition, which includes even general information about unsanctioned political rallies.

On March 13, 2014, the Attorney General banned three relatively small oppositionist websites (Grani.ru, Kasparov.ru, and EJ.ru), as well as the LiveJournal blog of anti-corruption activist Alexey Navalny. These resources remain banned in Russia today, though Navalny has relocated his blog to a self-hosted domain, which is accessible in Russia now, despite being blocked temporarily in January and February this year (also on the Attorney General’s orders).

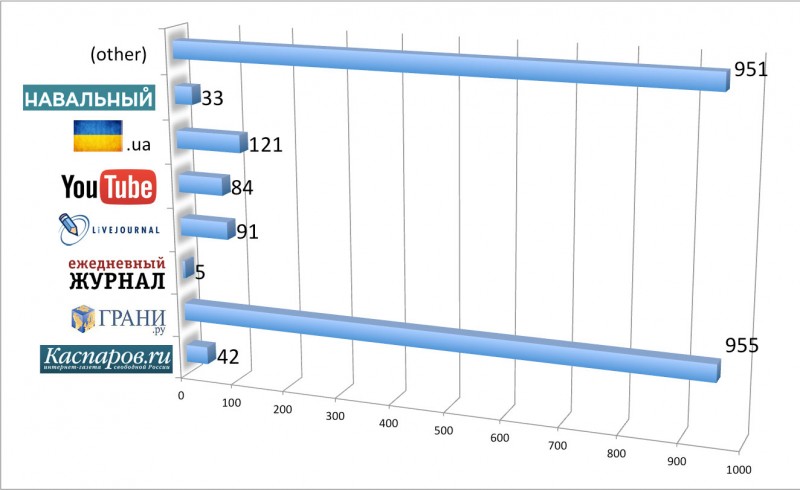

Of the three news sites listed above, Grani.ru has proved to be the most defiant, waging a sustained campaign to circumvent the government’s censorship with a barrage of mirror sites. According to the website Rublacklist.net, an Internet-freedom project run by the Pirate Party of Russia, more than 40 percent of the Attorney General’s 2,292 interventions online have been directed at Grani.ru. Compared with any other website, Grani.ru has consumed more of the Attorney General’s censorship efforts, by far.

Number of online interventions (blocking websites and unblocking websites) by the Russian Attorney General. Data according to Rublacklist.net. Graphic by Kevin Rothrock. (From top to bottom: other, Navalny, .ua websites, YouTube, LiveJournal, EJ.ru, Grani.ru, and Kasparov.ru.)

Speaking to the Russian-language service of France Médias Monde, Grani.ru’s general director, Yulia Berezovskaya, recently revealed that the Kremlin’s media watchdog agency, Roskomnadzor, still sends Grani.ru warnings about content that appears on its website, despite the fact that the website has been blocked in its entirely for the past 17 months.

Roskomnadzor’s warnings differ from the Attorney General’s decision to ban Grani.ru, insofar as the former targets specific content, identifying stories that supposedly violate one law or another. The March 2014 site-wide ban on Grani.ru and the other websites, however, didn’t specify anything, according to Berezovskaya. “We are blocked in Russia for an indefinite period, insofar as prosecutors claim that the ‘aggregate sum of the content’ on our website contains calls to unsanctioned protests,” she says. Grani.ru has lost all its legal attempts to challenge this situation, and it’s since taken the matter to the European Human Rights Court.

In her interview, Berezovskaya says she understands why her Russian journalist colleagues have declined to take a hard line against censorship, as her outlet has, but she expresses concern that the crackdown on small sites like Grani.ru is reverberating more broadly as a RuNet-wide chilling effect. Some larger news publications, Berezovskaya says, have even purged from their archives any links to articles published by banned resources like Grani.ru.

The future doesn’t look terribly bright for Grani.ru, either. Forced to relocate its permanent staff and offices abroad (Berezovskaya works from France), Grani.ru now only employs special correspondents inside Russia. The website’s revenue stream has also slowed to a trickle. Before it was blocked, Grani.ru was enjoying record traffic: roughly 150,000 readers a day. Today, after more than a year of being banned in Russia, that number has dropped to 40,000 visitors, and most advertisers have abandoned the website.

Aside from some modest donations from readers (which are difficult to collect, thanks to online payment systems refusing to work with the site), Grani.ru today subsists on a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy, an American foundation whose activities were recently banned in Russia, in accordance with a recent law that targets “undesirable organizations.” Now that NED has been blacklisted, it is conceivable that Grani.ru’s correspondents working in Russia could face criminal liability for participating in NED-funded work.

1 comment

Grani ranks #13 on top-20 hit-list of independent media that Kremlinists want gone: “The 20 Russian News Outlets You Need To Read Before They Get The Ax”: http://www.rferl.org/content/twenty-russian-news-outlets-you-need-to-read-before-they-get-the-axe/25317371.html