“My body is not a democracy. I choose”. Rally for a free and safe abortion, Santiago de Chile. July 25, 2014. Photo by Periódico El Ciudadano (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Since 1974, when the law was changed under Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship, Chile has been one of seven countries in the world that do not allow abortion under any circumstances. After democracy was re-introduced in 1990, there were several attempts to decriminalize abortion, but all of them, including a promise from president Michelle Bachelet to legalize it in case of rape or mortal danger to the woman, were unsuccessful.

When the Chilean constitution had to be changed in 1974, Senator Jaime Guzmán Errázuriz gave a speech about abortion that included the following: “The mother must have the child, even though it might be abnormal, even though it may be unwanted, even when it is the product of rape and even though the pregnancy may result in her death.”

Although the constitution itself remained vague and only “protects the life of the unborn,” Guzmán's discourse remains the best summary of the policy today.

By Bachelet's May 21 speech of this year, the promise had disappeared, but the debate had not. Every couple of months, the Chilean press runs a series of articles about very young girls who get pregnant, usually as a result of rape, sometimes by a family member and are not allowed to abort. This year, it was an 11 year-old girl, whose tragic story made her a symbol of the cause.

Mi cartel del día de la mujer dirá “Chile país en donde una NIÑA de 11 años puede ser MADRE DE SU PROPIO HERMANO. ABORTO LEGAL AHORA”.

— #ApagonFemenino (@BessyPrado) March 4, 2015

“My poster for Women’s day will say: ‘Chile a country where a girl of 11 can be the mother of her own brother. Legal abortion now.”

Chile is a catholic country in its roots, so it is unsurprising that the prohibition regarding abortion is only one of many sides of a broader societal issue.

Mensaje de los Obispos de Chile ante el proyecto de despenalización del aborto http://t.co/anQNWwcNTv — Iglesia.cl (@iglesiachile) May 26, 2015

“The bishops of Chile react to the project to decriminalize abortion http://t.co/anQNWwcNTv”

The contraceptive pill is sold over the counter at pharmacies, but the morning-after pill, an emergency contraceptive used retroactively to prevent pregnancy, is harder to get a hold of. The emergency contraceptive was legalized in 2002, after a long battle in the courts. Affluent Chileans could get it in private clinics, but most women had to resort to the national health service, which only provided it in case of sexual assault. From 2006 onwards, it was made available to women from the age of 14 without parental consent, but

On March 8, 2015 International Women’s day, an estimated 8,000 people marched in the streets demanding safe, legal abortions. A couple of weeks later, an estimated 5,000 marched “for life.” Siempre Por La Vida, a Chilean pro-life organization, wants to keep the law as it is at all costs.

I spoke with Rosario Lagos, president of Siempre Por La Vida, who believes that even therapeutical abortion (in case of mortal danger) is “completely unnecessary,” because “doctors in Chile have the moral and professional obligation to save the life of the mother.” She calls abortion a “false promise for mental ease.” Lagos told me women need “company, support and protection,” not abortions.

“And in the case of rape,” Lagos said, “it is fundamentally unjust to condemn the child to death and the rapist to imprisonment. Abortion also causes more harm than good.” According to Lagos, “scientific evidence” shows that abortion “causes more physical and emotional damage.”

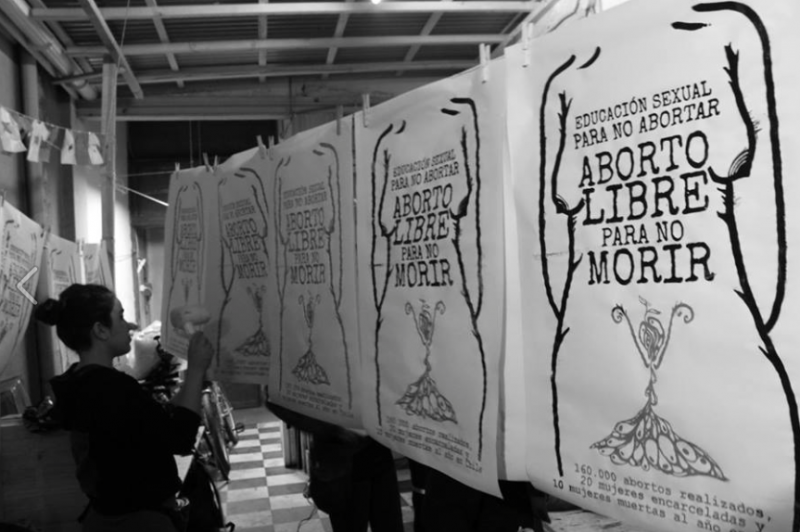

Javiera and Amanda of Serigrafia Instantanea are on the other side of the debate. They are part of a collective of artists that make posters and t-shirts to support social justice causes. “Chile is a conservative country, with a super conservative leadership,” said Javiera. “But why should they have the right to make decisions about my body? I don’t believe in the legalization of abortion for therapeutic reasons. We should have the right to freely make decisions about our fertility.”

Serigraphy brigade for free abortion rally in Chile. Image posted by Tomas Matala Aedo on Facebook.

Amanda talks about abortion as part of a much broader issue. “Abortion is only a symptom. We want to reclaim our bodies. Because abortion is already a reality in Chile. Rich women go to clinics; women without money have to resort to other measures.”

Every year between ten and twenty thousand women have illegal abortions in Chile. The taboo around this activity casts a massive shadow over the whole issue, so it is difficult to ascertain the accuracy of that figure. Human Rights Watch Latin America estimates that “a large part of the pregnancies in Chile are unwanted. About 35 percent end in abortion, which makes for around 160,000 abortions every year, 64,000 of which are on girls under 18.”

One of the organizations that helps women have safe abortions at home is Linea Aborto Libre, ran by Angela Erpel Jara, who is also a sociologist at the University of Chile. Every day between 8 and 11 pm, Linea Aborto receives as many as 15 calls from women seeking information on how they can have safe abortions using Misopostrol. To complement this service, they distribute books on the subject. Last year, after getting the books into local libraries, Linea Aborto Librea was sued three times, charged with practicing medicine illegally and inciting criminal activity. None of the charges stuck.

Erpel Jara and her colleagues focus on the practicalities and on the women they assist, instead of on the law. “We’re not interested in negotiating with members of parliament,” she says. “The law allowing therapeutic abortion is a waste of time. Women shouldn’t have to ask permission from male lawmakers to prove to male doctors that they have been raped or are in mortal danger to be able to make decisions about their own fertility.”

Erpel Jara only helps women with the treatment in their homes; legally, she can’t tell them how to get Misoprostol. But it’s not that hard. With the help of Google, a cellphone (the vendors communicate via WhatsApp) and 60,000 pesos (US$100), anyone can get her hands on the pills. A quick search yielded 30-plus individuals who have taken the risk of putting their phone numbers online, sometimes along with their names, and declare themselves to be sellers of Misoprostol. It’s unclear where they get the product. One study mentions a “Misoprostol mafia”, though the drug is available by prescription in most of Chile’s neighboring countries.

As an experiment, I sent text messages to a couple of the numbers and asked if they could get me Misopostrol. One of them answered instantly, asking what stage of pregnancy I was at and reassuring me they had “experience in the medical sector.” It became painfully clear that women who do this run a dual risk: they’re putting their health in the hands of a number found on the Internet, and their trust in clandestine salespeople. And if something goes wrong, a doctor could denounce them, landing them in prison.

At present there is little hope that the situation will improve. The president has remained silent, the law remains unchanged. The prohibition against abortion is ingrained in the Chilean constitution, a constitution, which, from its very first article, guarantees the safety of all citizens and the freedom to realize spiritual and material fulfilment—a freedom denied to hundreds of Chilean women each year.

2 comments