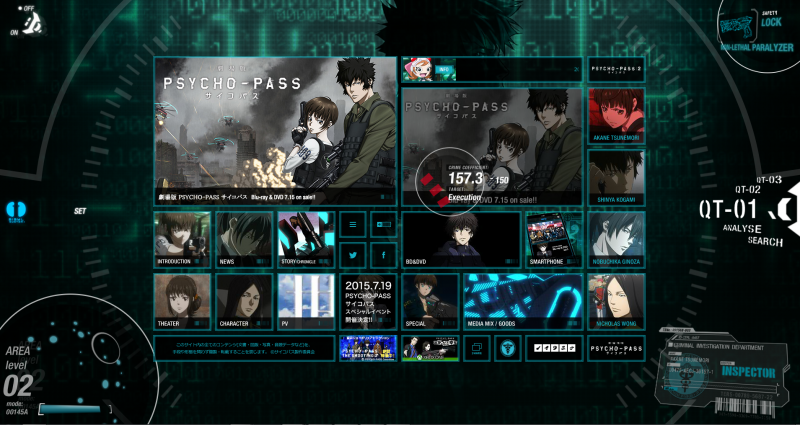

Screenshot of Psycho-Pass website. Pyscho-Pass is a dystopic anime created following the 3.11 disasters.

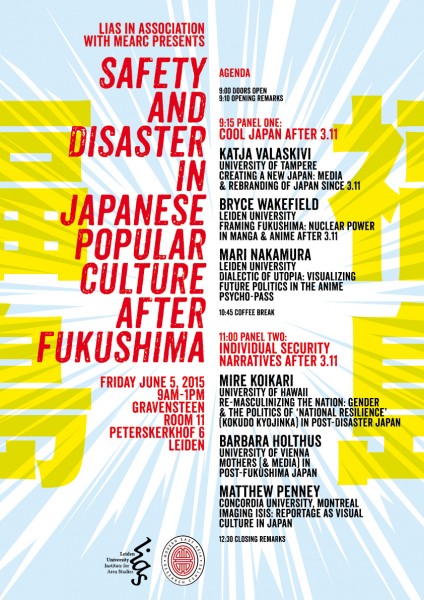

June 5 workshop at Leiden University. Image courtesy Bryce Wakefield.

Leiden University in the Netherlands will host Safety and Disaster in Japanese Popular Culture after Fukushima, a one-day workshop on Friday, June 5 featuring panel discussions that is open to the public.

Japan experienced a “triple disaster” on March 11, 2011, of a massive earthquake and devastating tsunami, which both led to the third crisis at the Fukushima nuclear power plant. The series of cataclysms is sometimes referred to as “3.11.”

Global Voices interviews Dr. Bryce Wakefield, a lecturer at Leiden University with expertise in Japanese politics and international relations. Wakefield is organizing the June 5 workshop and will be presenting that day on manga and nuclear power after the Fukushima disaster.

Nevin Thompson (NT): How significant an event was 3.11 for Japan?

Dr. Bryce Wakefield (BW): The earthquake, tsunami and nuclear accident seemed like game changers for Japanese society at the time. There was talk of ambitious projects to rebuild the communities damaged by these disasters, that the disasters might mark a new renaissance for Japan, that they would redefine the U.S.-Japan military alliance, and so on.

There were some immediate political and social effects after the disasters. Before the disaster U.S.-Japan relations had been damaged by a dispute over military basing issues in Okinawa, and bilateral rescue efforts immediately after the disaster changed the discussion in ways that enhanced the image of the alliance.

The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which had been in power almost continuously from 1955 until 2009, managed to exploit the disaster to show the weakness and inexperience of the new DPJ government, leading in part to LDP victory in 2012. Emphasis on specific issues—the value of volunteerism and civil disaster preparation, and the place of nuclear power in Japanese society—did become more prominent in national discussion.

However, a lot of the discussion about the disaster eventually became subsumed by existing narratives in Japan. Today Fukushima and disaster recovery are still important topics in the national discourse, but the wide-ranging shift in political and social perspectives that some were predicting did not come to pass as a result of the disaster.

NT: How has pop culture been transformed by the Fukushima accident?

BW: It depends what you mean by “popular culture.” As noted just now there was increased emphasis on volunteerism after the disaster. That could be an area of popular culture worth investigation.

One of the definitions of popular culture is that it concerns the practices of everyday life: how, for example, do people interact with the media. At our event, Barbara Holthus of the University of Vienna will be showing how parents concerned for their children’s health in the wake of Fukushima are coordinating their activities and using media, including social media, in new ways.

Similarly, Mire Koikari of the University of Hawaii will be looking at how notions of masculinity are asserted in popular attempts to make Japanese people more aware of the need for civil defense.

Another speaker, Katja Valaskivi of the University of Tampere, has written critically on the government’s attempts to incorporate notions of resilience into its post-Fukushima public diplomacy.

Popular culture is a wide ranging term, and as well as the usual images of anime and manga that people think of when they hear “Japanese popular culture,” we do need to examine popular phenomenon more broadly.

NT: How has manga and anime addressed the nuclear accident?

BW: Before the nuclear disaster, manga and anime were sometimes deployed in public relations efforts to support the notion that nuclear power was safe.

Although there are some post-Fukushima manga that have been labelled pro-nuclear “propaganda,” there have also been more critical voices. These critical voices, however, fit into major themes of the postwar period in manga and anime. Those themes stress the dark side of scientific progress stress the dark side of scientific progress.

Some darker works are also often pessimistic about power relationships in Japanese society and politics.

Mari Nakamura’s presentation looks at issues of surveillance within the recent anime, Psycho-Pass, for example. In the past couple of years there have also been a number of critical works emerging that evoke distrust in government narratives about nuclear power. Manga and anime have discussed critical themes in the past, and will continue to raise such themes in relation to Fukushima.

However, these are often presented in ways that stay away from difficult or challenging content, such as radiation sickness, out of respect for the survivors.

NT: The second panel discussion focuses on “security narratives”, and ISIS comes up as a topic. What is the connection with the Fukushima disaster?

BW: In his presentation, Matthew Penney of Concordia University in Montreal will be talking about the relationship between public discourse and popular culture in Japan in the context of recent discussion about ISIS.

He is focused on the notion of political punditry as a type of popular culture performance, and the notion of pundits as characters that have been cultivated across media platforms.

These characters are seen to be “experts” on a wide range of issues, but because their intellectual net is cast so wide, it is questionable whether they can offer real analysis instead of emotional commentary on a number of these issues.

As such, pundits are often exploited by people with agendas on the extreme left and the right of politics, and this is very evident in the case of discussion about ISIS. So what are the media dynamics involved that make these pundits voices of authority?

As I think Matthew will outline in his talk, there is also an obvious connection there to the Fukushima accident and the punditry that ensued thereafter.

NT: Can you talk a little bit about the Leiden University's connection with Japan?

BW: The Netherlands does, of course, has a significant historical relationship with Japan, with the Dutch holding exclusive rights to trade with Japan during the Edo Period. Today, Leiden is a sister city with Nagasaki, where this trade took place.

Leiden University was the first university outside of Asia to establish a chair of Japan Studies, in 1855. Today, in terms of first year student enrollment numbers, Japan Studies is one of the largest programs in the university’s very strong Faculty of Humanities.

We have been sending our students at Nagasaki University since the 1980's. Every year 10 to 12 top students go there for five months. Every student enrolled in the bachelor’s program has the chance to go to Japan for as part of their degree. It really is a great program.

Safety and Disaster in Japanese Popular Culture after Fukushima will be held at Leiden University in the Netherlands. Anyone interested in attending this half-day workshop can register here.