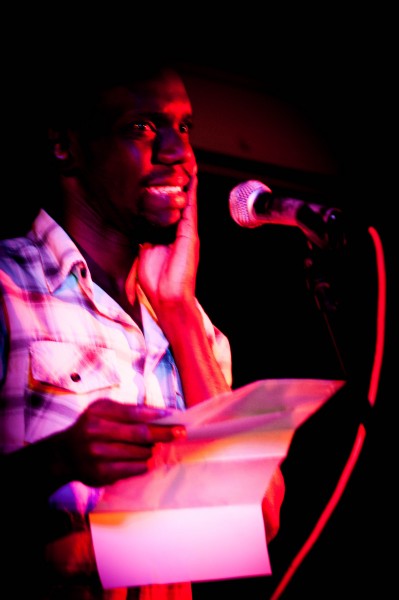

A poet on stage during a Fatuma’s Voice event in Nairobi, Kenya. PHOTO: Pernille Baerendtsen

The sun hangs low as the hosts of Fatuma’s Voice step on stage at a crowded venue in Nairobi. Words make the space hum. English mixed with Swahili and Sheng (local slang). People turn and twist mobile phones to capture photos, which are Instagrammed and tweeted with tags like #fatumasvoice. We are at Pawa254 [1], a creative hub situated between the university and State House in the capital of Kenya.

The darkness of the early evening embraces us, and the stark, bright light from the ceiling lamps bounces off the leaves on the trees outside the windows. The leaves reflect back a fluorescent green light, creating a fitting backdrop for what’s about to happen.

Fatuma’s Voice [2] is a weekly event where people are invited on stage to recite poems, make statements, perform music. This evening a group sharing their experiences with police harassment opens the show. The previous week they’d been doing improvised spoken word [3] street performances around Nairobi that the police perceived as a provocation. On stage the group recounts stories of how they were forced to roll in mud as punishment. Among the audience there is no doubt that these young guys are true heroes. The audience shows appreciation for their courage with loud cheering and applause.

“Poetry sets me free,” says Chris Mukasa, and delivers another image provoking metaphor: “The youth of Kenya are like time bombs. We are working to prevent explosions. If words are never let out, we’ll explode! Especially youth need to speak openly about what is going on in their minds. If you we don’t speak about things it will turn into frustration.”

The people behind Fatuma’s Voice are Chris Mukasa [4] and Nuru Bahati Shukrani [5], founders of the semi-virtual community, Kenyan Poets’ Lounge [6]. Sitting at a café on busy Moi Avenue in central Nairobi, the two young men explain that they started the initiative among students at the nearby university. The audience grew gradually, and in 2013 the event was transferred to Pawa254, a place also known for its founder, the Kenyan photographer and socio-political activist Boniface Mwangi [7].

For Mukasa and Shukrani it is also about taking social responsibility and about contributing to the fight for equal distribution of Kenya’s wealth. Fatuma’s Voice is named after a fictional woman who was born dumb, explains Chris Mukasa, adding that the average Kenyan woman utters 2,500 words a day. As Fatuma has not spoken for over 50 years, many words are trapped inside her, waiting to be spoken.

The Kenyan Poets’ Lounge Facebook group [8] has more than 58,000 members. The poems shared deal with everything from activism and politics to religion and romance. The space between fantasy and fact is central here. The space can release freedom of thought. Hence, Fatuma’s Voice’s most precious task is to provide space where fantasy can be given free rein. Mukasa’s and Shukrani’s next mission is to create more local platforms outside of Nairobi.

Es Taa: “Poems can put things which are difficult to deal with in words. I will not allow my culture or my tradition to reduce my influence. Writing poetry gives power to change things.” PHOTO: Pernille Baerendtsen

“People have heard me, not read me,” says Esther-Karin Mngodo [9] from the other side of the plastic table in the cafeteria in Tanzania’s national library, Maktaba Kuu ya Taifa, in central Dar es Salaam. Esther-Karin works as a journalist for the Tanzanian daily, The Citizen, where she writes about culture. When she writes poetry, her name is Es Taa.

If she’s going to reach a larger audience, it’s not going to happen by selling poetry in printed form. Therefore, spoken word events and social media make sense. They’re free, and the poet can practice her/his material and receive immediate feedback from the audience. In 2014, Esther-Karin received the Ebrahim Hussein Poetry Prize [10] for her work.

The themes of Esther-Karin’s poems include taboo subjects such as sexuality. When she shares a poem on social media or at a spoken word event, she’s is also testing the limits of how far she can go. People sometimes believe that her poems are drawn from personal experience, but she says that is far from the case, claiming the right to play with the space fiction creates.

X-FACTOR, WITHOUT THE JUDGES

On weekends, Nyumbani Lounge in Dar es Salaam functions as a concert venue and nightclub. Beams of light shimmer off in the chandelier hanging over the bar. The sofas and the dense red spotlight trained on the centre of the stage add a touch of glamour to the atmosphere.

Spoken word is also taking place here, in one of Dar es Salaam’s more well-heeled middle-class areas. The organisers, Nancy Lazaro Mwaisaka [11] and Neema Komba [12], have named the event La Poetista [13]. It runs twice monthly, and admission is 5000 TZS (2,5 euro). The principle is similar to Fatuma’s Voice in Nairobi—all are welcome to sign up to recite a poem or perform music.

Nancy Lazaro Mwaisaka writes poems herself. The audience listens in silence as she recites a poem about a young woman’s struggle to accept herself in spite of criticism and jealousy.

A man is introduced on stage as “Black Feet”. Clad in his “Tanzanian office uniform” of crisp shirt and neatly ironed trousers, Black Feet delivers a performance that veers between hip-hop and preaching.

The stage is open. People perform in English, “American” and Swahili. On taking the stage many cautiously announce that it is their first time. Many have brought friends and families. It is their applause that counts right now.

The approach is non-academic. Strict attention to the rules of poetic composition or style are not on the agenda. It’s as if those qualities step aside to make way way for joyful expression and exploration of the freedom to say exactly what comes to mind. But the young people who walk shyly on stage step down elevated.

“We are Tanzania’s X-Factor—only without the judges,” the MC exclaims in a fit of breathless enthusiasm as he winds up this evening’s session. It triggers the audience’s applause, which is spiced with chants and whistles.

Whether the location is a night club stage as in Dar es Salaam, or an activism hub such as Nairobi’s Pawa254, something is happening. Words want out. Cloaked in performance. Words about issues, which take personal courage to express in front of a crowd. What is this all about?

SPACE FOR FANTASY

One of the most important advocates for literature produced by Africans, and for unconventional ways of dealing with the spoken and written word, is the Kenyan publishing house Kwani? [14] (Swahili for “what’s up?”). Established in 2003, Kwani? publishes books, stages open mic events, and is working on solutions to make it easy for people to read books on their mobile phones. Kwani? is particularly known for mixing illustrations and texts presented in the languages people speak in Kenya.

The writer Binyavanga Wainaina [15] is a co-founder of Kwani?, and is known for challenging the West’s stereotypical perception of Africa. His 2005 satirical essay “How to Write About Africa [16]” sparked a global debate. In 2014, Times Magazine listed him among the world’s 100 most influential persons [17] after he created a stir with article titled “I’m a homosexual, mum [18]” on the blog “Africa Is A Country” (After that he said that his memoir, “One Day I Will Write about This Place [19]”, needed a new chapter to align with the truth.) On social media, people questioned the courage of a Kenyan man declaring his sexuality in a country where homosexual acts are a criminal offense. Some wondered if the declaration was real or fictional. In a blog post entitled “We Must Free Our Imaginations [20]”, Binyavanga outlined his dream of a continent where Africans do not need permission to indulge in fantasy.

Over half the population in East Africa is below the age of 15. Young people challenging tradition and testing the limits of expression is not new. Nor do spoken word activities stand alone; rather, they merge into a larger wave of exploration of new ways of doing things.

It takes courage and fantasy to imagine that things can be done differently, and some of this is already happening. Youthful politicians in Tanzania challenge the elderly’s perceptions that their candidacy can be taken granted. Activists in Nairobi walk in protest when MPs raise their own salaries, or when youth organize “My dress, My choice” protests advocating the right to choose one's own dress code. Fashion designers create new models based on traditional fabrics. Musicians fuse electronic vibes with old, African drum beats and name it “afrofuturism”.

Something is on the way. But, is it new?

POLITICS AND POETRY

Demere Kitunga [21] has established Soma Book Café [22] in a residential area in Dar es Salaam. In the garden, between the café and the library, the traffic noise from nearby New Bagamoyo Road is blocked out by big trees. Soma Book Café hosts spoken word and other literary events. It also hosts an annual short story competition for secondary schools, and offers a mobile street library for children in an adjacent, less privileged neighbourhood.

Demere, who is a writer, activist and publisher, has worked in education and publishing for decades. She hesitates to call spoken word a new trend.

“For what is our baseline? Do we go 500 years back in history, back to the fight for independence (early 1960s), or are we talking about right now?” she says. She draws lines between poetry and Tanzania’s history, and emphasizes particularly significant periods. The political climate has always influenced poetry and the level of freedom of expression.

Gerry Bukini steps on stage to recite a poem in Swahili. Blinded by the red spotlight, he tries to focus on the audience while he clicks his poem forward on his mobile phone screen. “I didn’t know I could write poems in my own language,” he says, during a break between performances. PHOTO: Pernille Baerendtsen.

“During the struggle for independence the papers printed nationalistic poems,” Demere says. “It still exists.”

Tanzania’s most popular national poet, Shaaban Roberts [23] (1909-1962) used poetry to formulate what kind of society he wished to see materialize after independence from the colonial powers. Today, the politician Zitto Kabwe [24], who is the most followed Tanzanian on Twitter, occasionally shares poems with themes like patriotism and responsibility.

Traditional poetry is still practiced today in Tanzania, while other forms of poetry have changed, along with globalization and general development. Utenzi [25], for instance, a kind of poetic recitation dating back to the 18th century, is still practised at weddings. Taraab [26]—Swahili poetry accompanied by music played on Arab instruments—is still performed traditionally. Today, taraab is also practised in a popular version known as “modern taraab [27]” at venues where female singers and smaller orchestras with electronic keyboards perform with texts renowned for their detailed narrations about sex and love.

When Tanzania introduced a multi-party political system and liberalized its economy in 1992, the country gradually opened up towards the world. This created a new space for media and culture, and the music genre Bongo Flava [28] was born. (Tanzania’s commercial capital is popularly named Bongo, which means “brain” in Swahili—it takes brains to make it in the big city! “Flava” is a swahilification of the English “flavor”). Bongo Flava was inspired by American hip-hop, but with lyrics in Swahili, and became a voice for many. Bongo Flava today has spread over many genres, and also spills onto the spoken word stage in Tanzania.

If spoken word can be categorized as a new trend, it is too early to say. “So far spoken word in Tanzania is only popular among a smaller segment where culture is already trendy.” says Demere Kitunga. Several factors will determine if this new wave of words will grow, and in what way. Economic development is one. The expectations for Tanzania making a profit on gas extractions are sky high. It is, however, difficult to predict if economic growth will result in investment in the cultural industries. Geography and technological access also play a role. It is not rural youth who right now enjoy the spotlight—this is an urban phenomenon.

In Tanzania it is not the university or the publishing houses which spearhead the development of art and culture. In Kenya the cultural industries are more dynamic, but in both countries, spoken word is driven by the youth, who have the energy and who are turned on by thinking outside the box.

Find African writers and poets on Twitter at https://twitter.com/Dunia_Duara/lists/writers-poets-africa [29]

The article was previously published in Danish for the Danish International Aid Agency’s magazine ‘Udvikling’ (Development), March 2015. The Danish version was slightly adapted.