Below is an edited version of “Mascots: the Cutest Social Police” by Christina Xu, originally published on the blog 88 Bar and republished here as part of a content-sharing agreement.

In the years leading up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the Fuwa (福娃, “dolls of good fortune”), the official Olympic mascots, were everywhere: on billboards, in TV ads, made into stuffed toys, and erected as mini-statues in malls and airports all across the country.

Since then, hyper-cute anthropomorphic mascots designed through public contests have become all the rage. In addition to being great for merchandising and photo opportunities, these mascots are also often used to encourage and model “civilized” (文明) behavior.

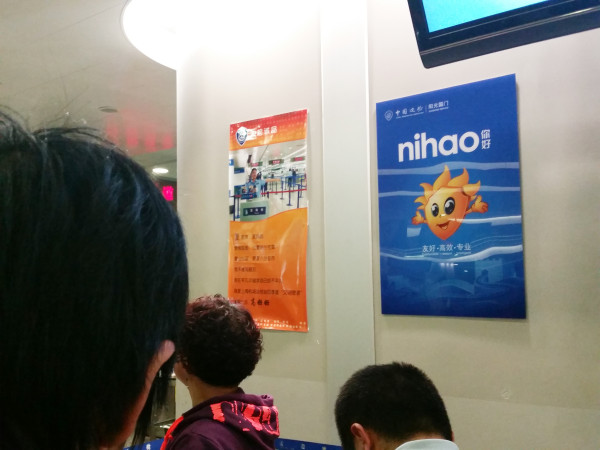

Tian Tian (天天, “Everyday”) is the official mascot of the “Sunny Border” branding campaign, a joint effort between several governmental departments to give the Chinese border control a friendlier face-lift.

A Tian Tian poster in the immigration line at Shanghai Pudong. Photo by Christina Xu

In posters around immigration areas (and in billboards near airports), Tian Tian greets visitors and promises them a “friendly, efficient, and professional” experience. In a press release promoting the campaign during its 2012 launch, Tian Tian was highlighted as being a hit with kids.

Tian Tian on a billboard near Shanghai Pudong airport. Photo by Christina Xu

Chang Chang (畅畅) was selected as the official mascot of the Shanghai metro following a three-month contest in 2009. You’ll spot him in signs and videos around Shanghai’s metro stations encouraging good behavior or issuing warnings, as well as in special merchandising booths in popular stations.

A Chang Chang toy poses with fan letters and next to a safety sign normally posted near the track that reads, “For your personal safety and convenience, please don’t loiter here during high traffic areas.” Image from SHMetro.

Tian Tian and Chang Chang are part of a growing bestiary of mascots for all kinds of faceless infrastructure. In my travels, I’ve spotted them for fire departments, banks, and a huge number of public spaces such as malls and airports. They seem to be primarily intended for display in the physical environment—as statues, characters in PSAs, merchandise, and signs and banners—rather than on websites or in social media.

The videos and signs they star in are part of a series of nationwide awareness campaigns to model “civil” behavior” and spread new norms about acceptable public behavior, specifically targeting newly urbanized migrants learning to share urban public spaces for the first time.

The mascots advocating these norms—don’t stand too close to the train tracks, do conserve tap water, don’t smoke indoors, do stand in orderly lines—increase the visual appeal and friendliness of these mandates, especially to the younger generation. These mascots represent not only an interesting part of China’s contemporary visual language, but also a soft mechanism (or accessory) for social regulation.