The October 2014 protest against acid attacks in Isfahan. Photo was taken by Aria Jafari for ISNA before he was arrested for photographing the local protests. His week-long uncharged detention ended on bail on November 1. ISNA publishes these photos with permission to reuse.

As the world celebrated International Women’s Day on March 8, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani insisted on his Twitter page that women should have “equal opportunity, equal protection and equal social rights.” Nonetheless, the struggle continues for a group of young Iranian women suffering from catastrophic physical injuries and psychological damage. These are the victims of Isfahan's acid attacks.

In October 2014, a series of acid attacks on women in the historic city of Isfahan created a fearful atmosphere and prompted rumours that the victims were targeted for not being properly veiled. Unofficial figures about the number of victims have varied. Local authorities initially confirmed two victims, according to Iranian Student News Agency (ISNA), while Fars News Agency collected the unverified figure of up to 13. No news agency could report an exact number. As such, no figure has been officially verified since.

Enraged over the news, citizens of Isfahan took to the streets to protest. Isfahan’s Prosecutor General attempted to appease the crowd by promising prompt prosecution of potential suspects. However, the protesters were dispersed by tear gas shortly after. Civil unrest followed in other major cities. In Tehran, a group of human rights advocates joined the protesters outside Parliament, which led to a number of arrests, including that of Mahdieh Golroo, a prominent women’s rights activist.

The gravity of these attacks and the unprecedented civil mobilization that ensued resulted in quite a bit of attention on social media at the time. In particular, focus turned to the Plan to Promote Virtue and Prevent Vice, a bill currently under the consideration of Iran’s conservative-dominated Parliament that would protect vigilantes who enforce Islamic dress and appearance for women, and the police's role in not arresting the attackers.

This first tweet depicts a graffiti image that says “Permanent Makeup Remover: Acid.”

طرحی از ماجرای #اسیدپاشی روی یکی از دیوارهای شهر مشهد pic.twitter.com/mh2xjOigrq — سپیده (@Sepi12_22) October 28, 2014

The story of #acidattacks on the walls of the city of Mashhad.

The second tweet is in reference to the prompt arrest of the makers of a “Happy” video by Iran's morality police, who boasted identifying and arresting the participants within hours. The image reads as: “We identify any suspect within 2 hours”.

فقط 2 ساعت #اسیدپاشی #اصفهان #بچه_های_ویدیوهپی #رئیس_بیمارستان_ضیائیان pic.twitter.com/AxgaxDmMLN

— نیاز (@khengekhoda) December 1, 2014

Only 2 hours #acidattacks #Isfahan #theKids_from_theHappyVideo #head_ofHospital_Ziaeian

Iranian conservatives typically propagated against such news going viral on Facebook, Twitter, and similar platforms. The Iranian online community remained focused on the topic for some time before it faded. Golroo spent 45 days in solitary confinement and was released on bail early January after a three-month detention in Evin prison. The opposition media outlets and human rights advocacy initiatives briefly noted the news of her release.

However, the volume of public engagement was hardly comparable to that of the date of her arrest. Nor did this update bring acid attacks back to any social media trend. The Iranian state’s failure to promptly prosecute suspects, furthermore, fuelled the overall neglect of this issue. As such, we should ask, have acid attacks been effectively archived?

A look at the data

The following graphs delve into the engagement with the topic over a four-month period on three social media platforms: Twitter, Google Plus, and Persian-language platform Balatarin. The selected websites are known for their appeal to different segments of the Iranian online community who represent distinct, and yet overlapping, socio-political interests. The graphs indicate the number of Persian content tagged with “اسیدپاشی“ (Persian for acid attack) on each of these platforms prior to the outbreak of acid attacks news (October 20, 2014) until shortly after Mahdieh Golroo was released (January 27, 2015).

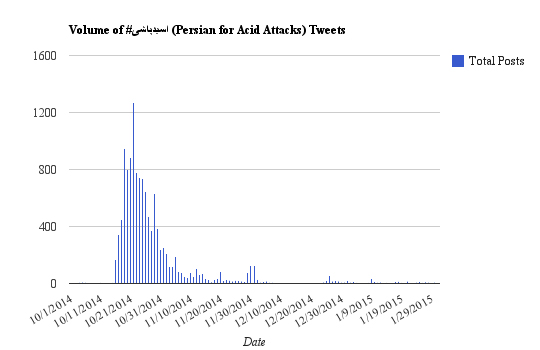

اسیدپاشی# (Persian for acid attacks) on Twitter between October 1, 2014, and January 31, 2015. Data used with ASL19's permission.

According to data exported from social media data analytics tool Crimson Hexagon, provided by the team at ASL19, an organization helping Iranians circumvent online censorship, 1,268 tweets were posted and tagged with #اسیدپاشی on October 23, 2014, one day after social unrest followed the outbreak of news. The hashtag pulse is fairly inactive toward the end of November, and rather invisible on January 27, 2015, when Golroo was released.

Balatarin

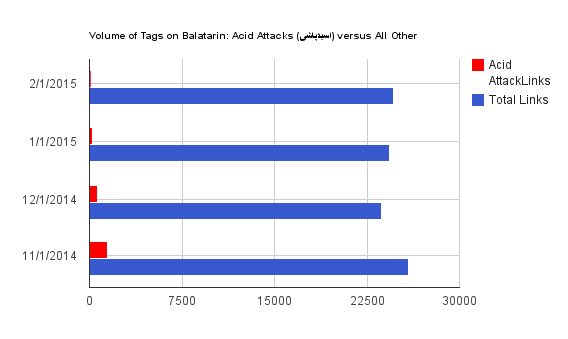

اسیدپاشی (acid attacks) on Balatarin between October 1, 2014, and January 31, 2015. Data used with Balatarin's permission.

Engagement on Balatarin peaked in October with 1,493 links that were tagged with ”اسیدپاشی” out of the aggregate of 25,853 (5.7% of total links), according to data exported from the Balatarin website backend, provided by the Balatarin team. The number dropped to 91 out of 24,656 in January (0.3% of total links). Balatarin currently hosts 84,792 users, according to the team.

Google+

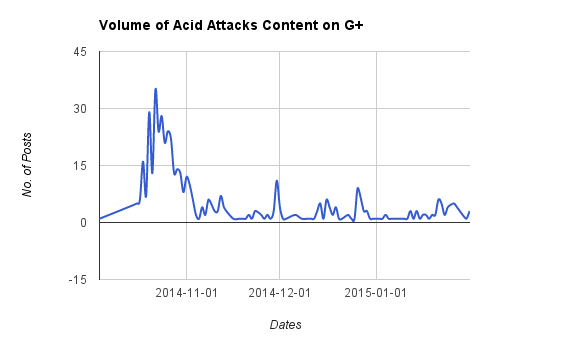

اسیدپاشی (acid attack) content on Google+ between October 1, 2014, and January 31, 2015. Query results used with NetFreedom Pioneers’ permission.

Between October 20 and October 27, when public opprobrium soared over the news, an average of 24 posts per day was published on Google+, according to data generated by a query that explored the application program interface (API) of Google Plus. Query results were provided by NetFreedom Pioneers, an organization that promotes the development of alternative technologies that enable the free flow of information. Less than five posts per day were detected in the last week of January. In a survey of 2,300 people in 2012, 37% of Iran-based Internet users had reported using Google+ regularly.

Remedy for social media's attention span

Iranian Internet users have historically demonstrated fortuitous interest in social and political issues. Social media campaigns are inherently ephemeral, let alone in Iran where the social scene fluctuates at an incredibly fast pace. More so, few Persian-language campaigns have proved sustainable.

Disturbing news typically cause public anxiety, generating reactions on social media that challenge accountable parties. Nonetheless, the same users may lose interest as soon as it seems they are failing to make a difference. The limited volume of user-generated content on acid attacks signifies the need for vigilant advocacy work to sustain awareness and demand accountability over matters of gender-based violence.

Punishments imposed on gender-based assaults in Iran are neither effectively compensatory nor deterrent. The insufficiency couples at times with vague legislation such as the Plan to Promote Virtue and Prevent Vice. The Basij para-militia group is explicitly designated for the enforcement of the plan. To provide equal protection for women, as Rouhani recently called for, public discourse against vigilante violence needs further dissemination. Accountability for such violence will then become an inherent part of public demands.

Rouhani’s statement on International Women’s Day was a timely reminder that state sovereignty comes with a responsibility to protect the population. The case of acid attacks, however, demonstrated the state’s failure to meet this responsibility with due diligence. Such inadequacy coupled with the short attention span of social media will marginalize the victims even further.

A sustainable social system that steadily urges accountability and augmented support for the survivors is key. Learning about the social impact of one’s online behaviour may keep users engaged with these important conversations. Intense stories such as acid attacks may then live longer and become more relatable through innovative and interactive approaches. It is time that advocacy work for Iran mapped alternatives for involving the public, not only at times of social emergency, but also in their aftermath.

4 comments