The state of media freedom in Bulgaria was bad in 2013 [2], according to Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index [3]. But in 2014, the situation deteriorated even further. Over the course of just one year, the country plunged 13 places on the list. At number 100 out of 180, it is now last in the EU, falling well below neighboring countries such as Hungary (64) and Serbia (54).

After a turbulent period marked by mass protests and political tension surrounding parliamentary elections, this record dive towards the bottom of the list has raised concerns within and outside the country.

The World Press Freedom report indicates that several independent journalists, many of them investigative reporters, faced serious threats from both government and non-state actors.

Gerard Choppe, president of the Swiss branch of Reporters Without Borders, saw the concentration of ownership and lack of transparency in the media industry as the biggest obstacles to media freedom in Bulgaria. He summarized this “bad news” at a press conference [4] where he issued the following diagnosis:

“България е лош пример по отношение на свободата на медиите.В разговор с български журналисти, те съобщават, че има много цинизъм, много автоцензура и силна липса на надежда. Симптомите не са никак добри. Журналистиката е огледало на обществото, следователно има още много какво да се направи. Дали трябва да се губи надежда и да се примирим – убеден съм, че не бива, нещата могат и ще се подобрят. В това отношение много може да помогне журналистическата солидарност”, каза Чоп. Самият той е бил дългогодишен главен редактор на швейцарското обществено радио, а сега е медиен консултант и се занимава с оценка на качеството на швейцарските медии”.

Bulgaria is a bad example in terms of media freedom. When one talks with Bulgarian journalists, they state there is a lot of cynism, much self-censorship and a strong lack of hope. The symptoms are not good at all. Journalism is a mirror of society, therefore there is a lot more to be done. Should we lose hope and put up with it? I am sure we should not and also that the situation might get better. In that regard, journalistic solidarity could help to a large extent.

At the same conference, Asen Yordanov [5], a member of the independent news site Bivol [5] in Bulgaria, spoke about the process of monopolization and buying of media that began after Bulgaria's accession to the EU. An investigative journalist [6] who focuses mainly on corruption in the judicial system, Yordanov pointed to Corporate Commercial Bank [7] (KTB), a private lender that played a significant role in monopolization and then declared bankruptcy [8] in 2014. According to Yordanov and Darik Radio journalist Prolet Velkova, the bank had a significant influence on the media sector between 2011 and 2014.

Corrupt Media and the Bankruptcy of Trust

In an interview with The Guardian [9], Bulgarian journalist Lada Trifonova described an incident that she says “encapsulates” much of the corruption and lack of transparency in Bulgaria's media sector today:

Reporters from the Franco-German television network ARTE were prevented from filming a property owned by one of Bulgaria's richest and most contentious politicians, the oligarch and media owner, Delyan Peevski.

His security guards and police subjected the journalists to unnecessary identity checks. Meanwhile, the Bulgarian video operator – who was hired by ARTE from a local TV channel – was phoned by his boss and ordered to delete the footage.

On June 14, 2013, a parliamentary vote to appoint Peevski to head the country's National Security Agency triggered anti-government protests [10]of thousands of people.

Trifonova, a former journalist and currently a post-doctoral scholar, has called on the EU to freeze funds intended for so-called “communication strategies”. She adds:

Four years ago, the then biggest foreign media owner in Bulgaria, the German conglomerate Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (WAZ), sold off all its titles. Its director explained that it was retreating due to “widespread abuse of power” and “the close intertwining of oligarchs and political power, which is poisoning the market”.

In subsequent years, the country's largest media organisation, the New Bulgarian Media Group (NBMG), was supposedly owned by Irena Krasteva, mother of Delyan Peevski.

Deutsche Welle Bulgaria also published an article with the headline “The big plunge” [11] that included several quotes from lawyer Alexander Kashamov and political scientist Parvan Simeonov, in which Kashamov claimed that the controversial appointment of Delyan Peevski was one of the key reasons that Reporters Without Borders gave Bulgarian media freedom such a low rating in 2014. He also added that the protests have raised public trust in social networks as a “communication substitute” for traditional media.

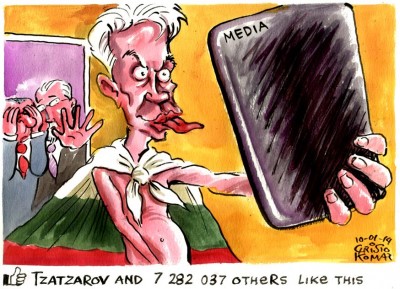

Caricature of the Bulgarian far-right politician Volen Siderov and media by Christo Komarnitzki, used with permission

The Independent Media Camp

The daily analytic website E-vestnik [12] is among those online media that are critical towards media dependency trends and government influence over journalists’ work. In one [13]of its analyses of the Bulgarian media, the online daily made collages of the front pages of a popular daily newspaper which published portraits of Prime Minister Boyko Borisov for several days in a row along with puff pieces of Borisov and his government.

Due to their objective and non-commercial line, many independent media earn little money from advertising, but still have a small and steady audience, mostly of people who search for alternative sources of information.

According to Simeonov, the media space has since been fragmented into “camps” that have tried to shed any influence and tone of Bulgaria's politics and systems of yesteryear. He further concluded:

В България липсва доверие към публичността. Налице е презумпцията, че всичко е платено или може да се купи. Дефицитът на морал е повсеместен. Това твърдение се отнася и за политиците, и за медиите, и за хората, които коментират политика, за всички, които имат допир с тях. “Свободата” на изразяване в българските медии достига абсурдни измерения.

In Bulgaria there is a lack of trust towards publicity. One has the presumption that everything is paid or that it could be paid. The moral deficit is [present] on a mass scale. This refers to the politics, as well for the media and people who comment on the politics, for everyone who had any interaction with those media. The “freedom” of speech in the Bulgarian media reached absurd dimensions.

Despite the current outlook, there may still remain a light at the end of the tunnel in 2015 — while decline can be endless, so can improvement.