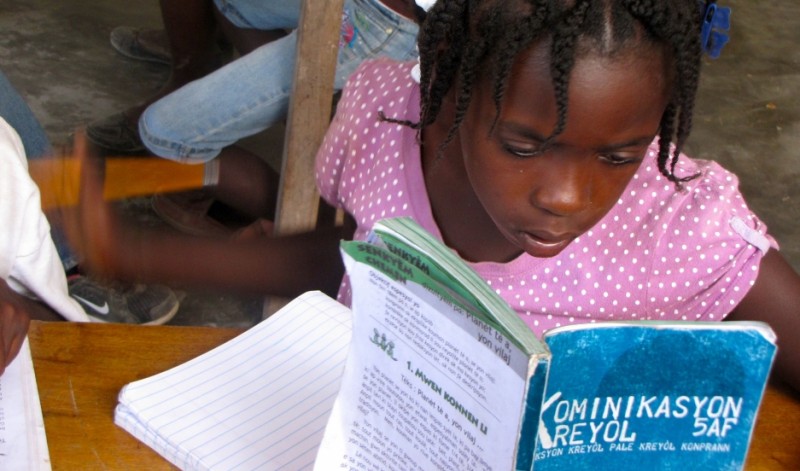

A 5th grade class at the Matenwa Community School in Haiti. Credit: Amy Bracken (Used with permission)

This article and a radio report by Amy Bracken for The World in Words originally appeared on PRI.org on December 22, 2014 and is republished as part of a content-sharing agreement.

Frandy Calixte is an 11-year-old boy who lives in a small village on the drought-prone island of Lagonav, Haiti. Sitting outside his house with his mother and teacher, he tells me he wants to be a nurse when he grows up, but his mother corrects him.

“Doctor,” she says, and he amends his answer.

Almost everyone here is a small farmer; higher education is virtually unheard of. But Calixte is bucking the trend by going to a different kind of school: The Matenwa Community School, just down the rocky road from Calixte’s house.

Matenwa is also bucking the norms of Haitian education. At the start of an all-school assembly, students stand up and share what’s good and bad — a lesson they enjoyed, or how they didn’t like the behavior of other students or even teachers. In class, students sit in a circle, following the school’s philosophy that children should be seen, heard and treated with respect.

There's another essential part of the school's method, the staff says: teaching in the students’ native language, Creole, instead of French.

Only an estimated 5 percent of Haitians are fluent in French, but it's still the language of government-funded textbooks. “When I was in school, I never really learned French,” says Calixte’s mother, who calls herself Madame Frantz Calixte. When I ask how she succeeded in school, she laughs. “I didn’t really pass my exams,” she says.

But of her sons? “They’re learning better than I did,” she says.

Abner Sauveur, who grew up in the village of Matenwa, was also taught entirely in French, despite not being able to understand everything. When teachers got frustrated with the language barrier, he says, they lashed out — literally — at their students.

“The way they beat me in school, I knew the system was bad,” he says. “People can’t learn like that.”

Sauveur never finished high school. But, in 1996, he and American teacher Chris Low co-founded the Matenwa Community School to provide “education that allowed people to reflect and share their ideas,” he says, “education that lets them learn better.” Using Creole was a necessity.

Matenwa uses Creole in all its instruction and textbooks through the third grade, when French is introduced as a second language. After that, textbooks for subjects like geography and history are all in French, simply because such books still aren’t available in Creole.

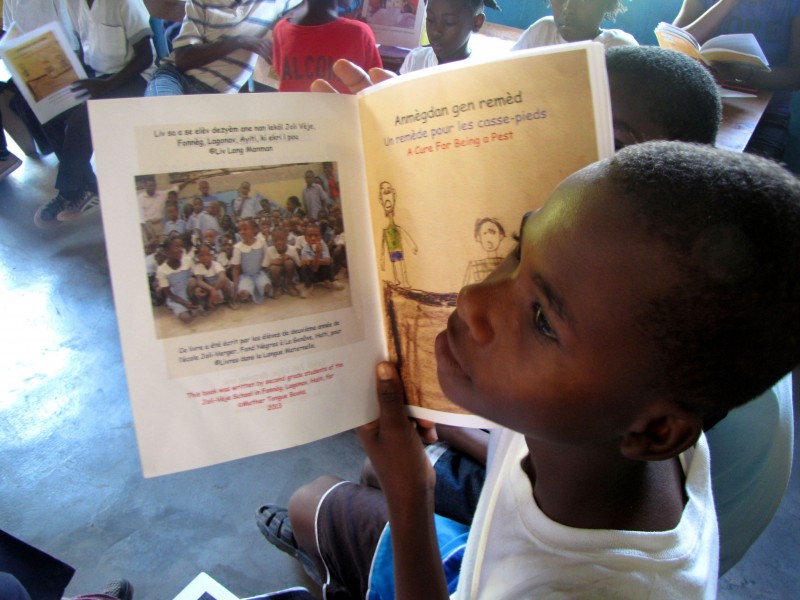

Matenwa’s co-founders hope that one day all books will be in both French and Creole. For earlier grades, the administration raises money to buy Creole books, and students make their own.

Fifth-grader Kervenson Succès reads a student-authored book, “A Cure for Being a Pest,” printed in Creole, French and English. Credit: Amy Bracken (Used with permission)

But many parents still believe French is the language of education, even in the earliest grades. They believe its spelling and grammar are more established than Creole, and that the earlier children are exposed to French, the better off they’ll be — even if they don’t understand at first.

“When the Matenwa school started, it was very difficult,” Sauveur says. “There were parents who would withdraw their students from school because we were teaching in Creole.” But he says those parents have returned their kids to Matenwa. Now political leaders from the prime minister on down are calling for more Creole education, and some are calling Matenwa a model.

Jonès Lagrandeur, the superintendent for the more than 200 schools on Lagonav Island, was also against Creole instruction at first. “Of course! Because of the way we were raised,” he says. “But then we came to better understand it. I was a skeptic, but now I’m a die-hard fan. Since Matenwa came along, we’ve turned a page in history.”

Matenwa also offers “mother tongue” training to educators around the country, but mostly works with neighboring schools. Lagrandeur claims that’s why national exam scores on the island this year were the highest ever.

Michel DeGraff, a Haitian linguist who works at MIT, says tests already show the Matenwa students’ Creole reading skills are almost three times the average score for 84 mainland schools tested by the World Bank.

DeGraff says he can tell French-based education isn’t working just by hearing people study. “It’s this sing-along type of tone, where often they break the sentence in the middle,” he says, “which means that they don’t understand what they’re studying.” It's the same kind of studying he did as a child, when Creole was disdained at his schools.

Now, as a member of the new Creole Academy, DeGraff is now tasked with promoting the language in all areas. But his main focus is education, including tools to help teachers teach science in Creole, and the translation of 21 math computer games into Creole.

Back at Matenwa, I visited on a Friday, when educators gathered for mother tongue training. They got pointers and books, and they discussed how they'd go back and train more people themselves.

“In the beginning it was just us who were teaching in Creole,” says Abner Sauveur, the school's co-founder says. “Now there are 10 schools who come here for training, every month. When I look at that experience, I believe that after 15, 20, 30 years, I might be dead already, but it’s possible that the system will be completely changed in Haiti.”

But at the training session, Sauveur distributes manuals that seem to have nothing to do with how to teach in Creole. They’re about stopping corporal punishment, communicating productively with students and protecting kids from sexual abuse. So is Matenwa a model because of Creole, or because of that attention to the rights of children?

I ask the teachers: Wouldn’t this school be influential even if all the classes were in French?

Their response? This could never happen in French.

The World in Words podcast is on Facebook and iTunes.

4 comments

See, http://www.nospank.net.