A Mexico City's government employee tries to clean graffiti of the number “43” off a municipal. “43”, representing the number of students who were “disappeared” from their school in Ayotzinapa in September 2014, has become a symbol of protest for many Mexicans. Photo by Robert Valencia.

A few weeks ago I visited Mexico. My trip there meant more than witnessing the turquoise waters of Cancun’s Isla Mujeres, or the urban sprawl of Mexico City, or stimulating my tastebuds with Mexico’s eclectic cuisine. It was an exploration of the country’s very heart and soul, and how Mexicans cope with injustice today.

Mexicans are known for their charisma—theirs is the Latin American country most visited by tourists. From a cheerful “Buenos días!” on the street to an unsolicited “Buen provecho!” (“enjoy your meal”) in a restaurant, the legendary Mexican warmth is always in evidence. But Mexicans’ courtesy and their rich and noble culture have not got in the way of the anger and courage they have had to adopt in order to deal with injustice and corruption.

Ever since the disappearance of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa School three months ago, Mexicans feel even more enraged due to the loopholes found in the investigation. In the first weeks of November, Attorney General Jesús Karam announced that the apprehended suspects confessed to “killing” the 43 students. But their remains—save those of one student—are yet to be found, and many do not believe the official report. The federal government has placed the blame on criminal groups so that it won’t be held accountable; otherwise the case would be ruled a crime against humanity and could be taken to international tribunals.

On November 9, Proceso, one of Mexico’s leading investigative magazines, published a host of questions Mexicans have been asking: Why are federal agents not being considered accomplices in the disappearance? How is it possible that three gunmen could subdue 43 students? How come people like Alejandro Solalinde, a local priest, knew what happened a month before the Attorney General did?

In the week of November 17—the eve of the anniversary of the Mexican Revolution—a massive protest was in the works. On November 17 I had the opportunity to meet Reed Brundage, former employer of Washington DC-based Americas Program, in Mexico City’s Coyoacán neighborhood. Over several cups of coffee, Reed offered this analysis of what’s happening in Mexico: “It as if somebody grabbed a knife and cut its insides open to discover a cancer that’s eating this country from the inside.”

As deep and visceral as this diagnosis sounds, Mexicans do want to take matters into their own hands so as to heal the nation. Unlike in previous years, they’re daring to defy President Enrique Peña Nieto, whose PRI party ruled Mexico for 70 years during the last century. Peña Nieto has not offered a concrete and coherent plan of action, and his government is grappling with a population—particularly the young and educated—that is fed up with the uncertainty. Although some experts don’t believe that a “Mexican Spring” is taking place, the population is nevertheless unwilling to believe tall tales and are now demanding the truth.

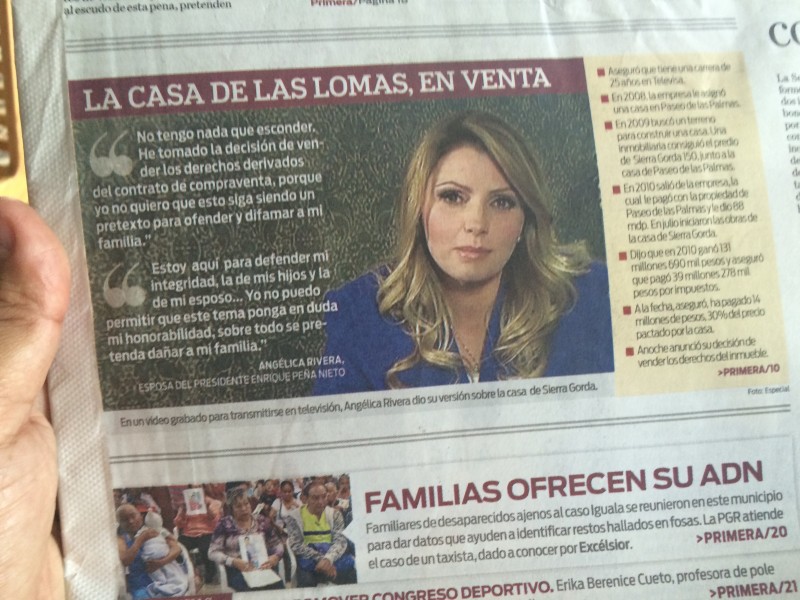

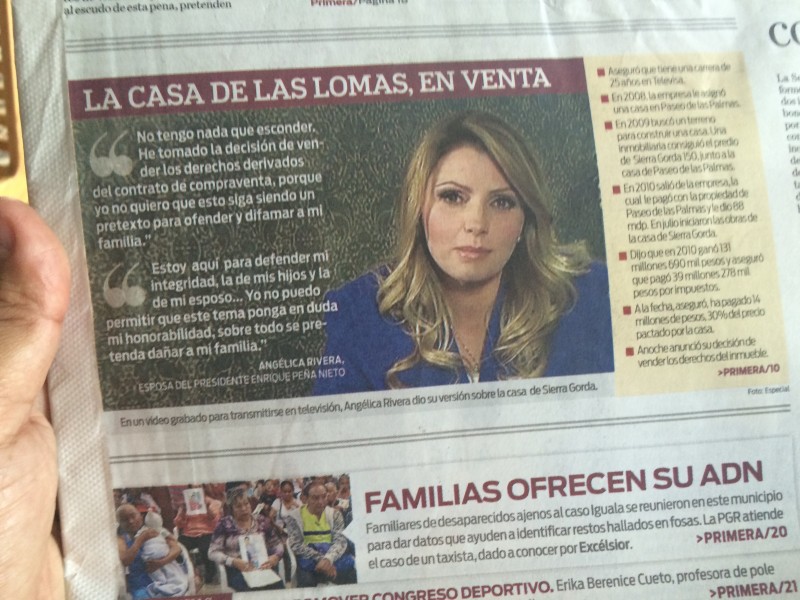

The US$7 million house, purchased by the Peña Nieto family added insult to injury. On November 17, first lady Angelica Rivera declared on TV that she bought the house with the money she earned as an actor at Televisa, Mexico's largest TV company. Her speech did not convince Mexicans.

One clear example of Mexico’s skepticism was the aftermath of first lady Angélica Rivera’s TV appearance that same week, explaining the purchase of a US$7 million dollar mansion in one of Mexico City’s most luxurious neighborhoods. The purchase had exacerbated Mexicans’ indignation, as they questioned the source of the funds Rivera used to buy the house. Rivera claimed the money was the sum of all the work she had done at TV channel Televisa, where she worked as an actress in the 1990s and 2000s. An investigative report by Mexican journalist Carmen Aristegui, however, showed that the house had been constructed and licensed by a company familiar to Enrique Peña Nieto when he was governor of the State of Mexico. In light of this revelation, very few Mexicans believed that Rivera could afford a multi-million mansion for her work in Televisa, as they claim that not even Hollywood artists would be able to acquire such a costly estate. Despite her pledge to return the property to avert more damage to Peña Nieto's image, Mexicans did not believe her version of the story, and out came the Internet memes.

[1]

[1]In this meme Hollywood actors Jolie and PItt say, “We'll go straight to Mexico. Televisa pays better.” Many Mexicans don't believe first lady Angelica Rivera could have earn enough at Televisa to purchase a US$7 million mansion. Photo from Twitter feed of @YobyJackson.

The only way to cure this cancer is for the federal, state, and municipal authorities to be as transparent as possible when it comes to judicial processes, as well as to be held accountable for their actions. The current and upcoming administrations must heal corruption problems inside their institutions—chiefly the judicial branch—as well as eviscerate municipal and state governments that are heavily influenced by drug cartels and criminal groups.

If Peña Nieto is unable to do this, the same population could rise up in arms to stem Mexico’s metastasis, and call for a referendum—or worse, reorganize as vigilante units as happened in the Michoacán state. The final cure would be for Mexicans to gain an understanding that Mexico’s destiny is everybody’s responsibility, and that the government’s actions must be thoroughly scrutinized.

Mexicans have managed to combine courtesy with courage. As the taxi driver who dropped me off at the airport said: “Behind Enrique Peña Nieto one can see the presence of [former president] Carlos Salinas de Gortari. Don’t get me wrong, my friend: Mexicans are good people, but we’re not fools.”

The Mexican press has kept track of the country's indignation since the disappearance of Ayotzinapa's 43 students. This newspaper's front page shows a concerned Jesús Murillo Karam, who has been criticized for the lack of concrete answers with respect to the case. Photo by Robert Valencia.

Robert Valencia is a writer and Latinamericanist based in New York City.

[1]

[1]