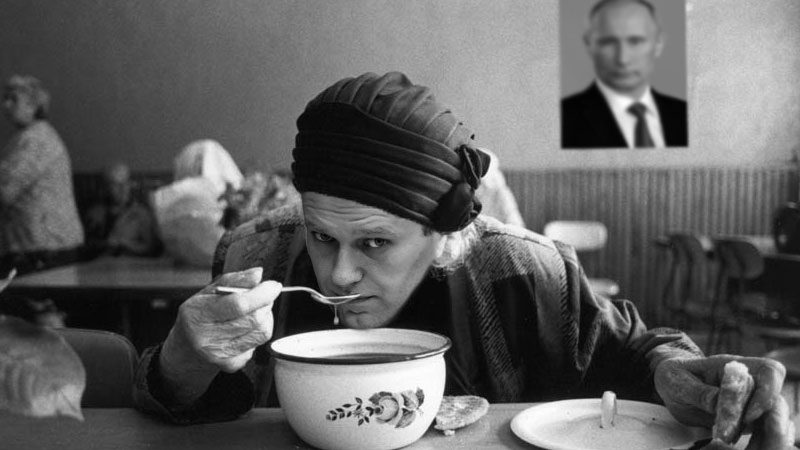

Alexey Navalny as a Kremlin soup kitchen guest. Images edited by Kevin Rothrock.

There are certain news outlets in Russia you don’t expect to publish stories accusing the government of funding Vladimir Putin’s enemies, but that is exactly what happened last week, when LifeNews released a story, titled “The Kremlin Secretly Finances Navalny.” The article claims the wife of Navalny’s close associate earned 100 million rubles (more than $2 million) in state procurement contracts, in the two years before Navalny’s 2013 Moscow mayoral campaign.

LifeNews pulled the story from its website shortly after publication. The author, Anastasia Kashevarova, the political desk chief at Izvestia (another subsidiary of News Media, which also owns LifeNews), immediately wrote on Facebook that she “was apparently fired” from her job. “It’s because of that jerkoff Navalny,” she complained, in a post that attracted 131 mostly unsupportive, often scathing comments.

Many of Kashevarova’s readers thought it ridiculous that she blamed Navalny for her evident dismissal, rather than the higher-ups at News Media or the officials in the Kremlin, who allegedly phoned LifeNews to demand that the story be removed. Kashevarova had more to say, however. “Screw these bureaucrats in the Kremlin,” she wrote a few hours later. “Naturally, they’re going to deny everything, so the project they’ve spent so much money on won’t die.”

It turns out Kashevarova will keep her job at Izvestia, and LifeNews even restored her article to its website later in the day. A few days after that, Duma Deputy Evgeny Fedorov formally appealed to Russia’s Attorney General and the federal Investigative Committee, demanding an investigation of the allegations presented in Kashevarova’s piece. “That some high-placed officials are financing Navalny and the opposition is obvious,” Fedorov told Izvestia, after submitting his request.

Kashevarova has said repeatedly that her article contains “100% proof” that the Kremlin funds Navalny’s political activities, but the text itself hardly lives up to this claim. In fact, the article makes just one weak effort to show that Navalny actually benefited in any way from the procurement contracts: it quotes Dmitri Gorobtsov, a Duma deputy who sits on an anti-corruption committee, who says conspiratorially—and without any evidence—that Russian taxpayers are funding a whole slew of oppositionists, including Navalny.

Is Gorobtsov’s speculation the “100% proof” Kashevarova wrote about earlier? Whatever the case, she seems optimistic that investigators will uncover more evidence of Navalny’s secret government funding. When that happens, she writes on Facebook, Russian police will be faced with a question: “cover it up and end up accomplices or blow the roof off the whole thing.”

Is it strange that a journalist at one of Russia’s most pro-Kremlin newspapers speaks this way? Political analyst Tatiana Stanovaya addressed this question in a recent column for Slon.ru, where she concluded that Kashevarova’s article is most likely part of the eternal war raging within the Russian elite for Vladimir Putin’s attention and trust. According to Stanovaya, the LifeNews piece tried to send Putin a message that read something like, “Tsar, the boyars have gotten out of hand and it’s time to sweep out the ‘sixth column!’” (The “six column” phrase, incidentally, is a favorite of controversial political scientist Alexander Dugin, who uses the term to identify officials within the Russian government working secretly to undermine the country.)

The public is left wondering, however, if there’s any truth to the claim that the government funneled money to Navalny’s political efforts. Absent any evidence that the procurement money ever reached Navalny, there is still the 2013 Moscow mayoral election, when Sergei Sobyanin, Moscow’s mayor, and Vyacheslav Volodin, Putin’s first deputy chief of staff, reportedly intervened on Navalny’s behalf, to keep him in the race and out of prison.

Episodes like this suggest it’s not entirely insane to think some people in the government are helping Navalny—that Russia’s opposition, just like its “independent media,” will always require some kind of support from the country’s powerful.

1 comment

An opposition is a precious asset of a ruler, because if there’s no opposition who will believe that the ruler is democratic? who will invite him to meetings?who will shake his hands?