As Darth Vader from the Internet Party of Ukraine voted on Sunday, voters used crowdmaps and hashtags to report on election fraud. Images mixed by Tetyana Lokot.

As Ukraine went to the polls this past Sunday, October 26, to choose its new parliament amid ongoing unrest and conflict in the East, voters once again turned to the Internet to seek information, report election violations and vent their frustrations about the process on social media. RuNet Echo looked at the most popular online tools and how they were used.

The elections themselves have so far had positive feedback from observers: Ukraine’s Voter Committee has reported three times fewer election violations this time than in the 2012 parliamentary elections, and the overall turnout was close to 52%.

The Ukrainian East, of course, fared worse, since swathes of both Donetsk and Luhansk regions are still controlled by the separatists. 1.5 million people in the Donetsk region (45%) did not take part in the elections, while the self-proclaimed “Luhansk People's Republic” announced that residents who participated in the elections were “to be judged by martial law,” and any members of the precinct and district election commissions would be “shot dead.”

Ukrainians have spent considerable time on social media discussing the relative merits of parties and candidates competing in the parliamentary run-off, and some political forces clearly took advantage of the viral marketing possibilities of the Internet. The Ukrainian Internet Party released a whole cast of Star Wars characters to run for seats in the parliament, with Darth Vaders, Chewbacca, Yoda and Padme Amidala competing for billboard space and tweet mentions with boring humans.

Of course, Ukrainians don't just go online to watch viral campaign videos: the civic efforts to make the voting more productive and transparent this year are more visible then ever. Activists working on election-related web services are primarily concerned with raising awareness of the party platforms, educating voters about who is running for which party, and providing the means to report election violations.

With talk of lustration and anti-corruption sentiments running strong, it seems especially important to know the backgrounds of the candidates for seats in the parliament. Several citizen projects have created online databases to provide helpful histories for each person competing in the elections, both those in the top spots on the party lists, and those competing in the district single-mandate elections. The “Chesno” (Honestly) citizen movement has a search bar on their website, where anyone can enter the last name of any candidate to find out whether they have a murky past. Websites like Vyboromat (Electomat) and Novateza (New Thesis) allow users to lean about the political agendas of each party: citizens can answer a series of questions about their preferences on key policy issues, and see which party's promises are closest to their stance.

The search bar on the Chesno website gives you a chance to learn about any candidate in the elections. Screenshot from chesno.org.

Digital technologies and social media platforms proved to be a significant component of the organizing, mobilization, and information dissemination tactics used by Euromaidan protesters, and some of those tactical lessons seem to have trickled down into civic efforts around the elections. Vitalii Moroz, head of new media at Internews Ukraine, says there is definitely more sophistication in the tools offered this time around:

Онлайн-платформи та додатки для українських виборів у 2014 році стали більш рознамітними й технічно складнішими аніж це було у 2012 році. Рішення стають все більш інтерактивними та заторкають різні аспекти виборів – від спостереження до обрання партій за критерієм ідеології.

The online platforms and apps created for the Ukrainian elections in 2014 have become more varied and technically complex then they were in 2012. The solutions are becoming more interactive and address different aspects of the elections—from monitoring to selecting parties based on their ideology.

Crowdmapping has become a staple of election monitoring efforts in Ukraine. During the 2012 parliamentary elections, three separate maps were set up by local civic organizations to engage citizens in reporting elections violations via email, text message or website submissions. This year, OPORA citizen network recreated their crowdmap and has received close to 900 reports of possible violations from all over Ukraine.

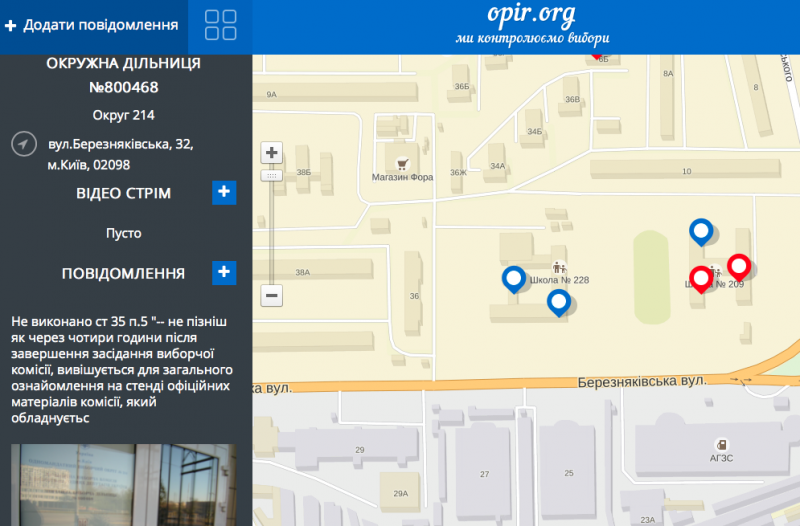

Another crowdmapping initiative, Opir (Resistance), was built by volunteers who banded together during the Euromaidan protests. The project combines an online map with Android and iOS apps, to provide more opportunities for reporting suspicious activity in the polling stations to Ukrainians who are increasingly using the Internet on their smartphones. Besides submitting reports and photos/videos of incidents, users can sign up to join mobile monitoring groups that combine drivers, lawyers and journalists and travel between precincts to monitor the voting process.

An example of a violation report at a precinct in Kyiv on the opir.org. website. Screenshot from opir.org.

Ukrainian authorities also jumped onto the citizen reporting bandwagon: the Ukrainian State Security Service created a dedicated portal where voters could upload photos and videos of purported violations of election procedures. The website has a form for submissions, but does not show the results on a map and generally looks somewhat forbidding, so the state still has a lot to learn from the brighter, more interactive civic web services.

OPORA network also banded together with the Institute of Mass Information, a media NGO, to create a helpful Andriod app for journalists covering the elections. The app, Elections 2014, is chock full of legislative documents, training manuals for election observers, and template forms for reporting violations (both election-related and concerning freedom of speech). The app's main goal was to provide reporters with an arsenal of tools to protect themselves and allow them to cover the elections more effectively.

The citizen-driven online tools certainly make a difference in the level of transparency, as they provide yet another safeguard against mass attempts to manipulate votes and report fraudulent results to the Central Election Commission. But much of the reporting also happens spontaneously, mostly on Facebook and Twitter (check out the #UkraineVotes hashtag for a taste.) Moroz, who has been observing the Ukrainian social media sphere closely during election seasons, says there is a constant stream of opinions and reports from all over Ukraine—but it's getting harder to track:

Увага користувачів розсіюється між різними платформами у порівнянні з 2009, 2010 та 2013 рр. Щось схоже сталося з Твітером – раніше ключовими хештегами були #elect_ua та #вибори2012 – нині їх багато – #elect_ua #вибори2014 #выборы #вибори #опора

The users’ attention is being diffused between different platforms, as there are more of them compared to elections in 2009, 2010 and 2013. Something similar is also happening on Twitter—whereas before we had two key hashtags, #elect_ua and #вибори2012, this year we have many more: #elect_ua #вибори2014 #выборы #вибори #опора.

Increased availability of dedicated tools for reporting violations and open platforms for exchange of opinions are definitely conducive to a healthier election climate in Ukraine. But if you follow the reporting (the violations were not many, but they were there) and the heated discussions of exit polls and election results on Twitter and Facebook, it's clear that not everyone is happy with the make up of the new parliament and what it might mean for Ukraine's immediate future. Regardless of their political sympathies, Ukrainians will probably need to get into the habit of monitoring those in power and get used to holding the new MPs accountable using every means available, both online and offline.

3 comments