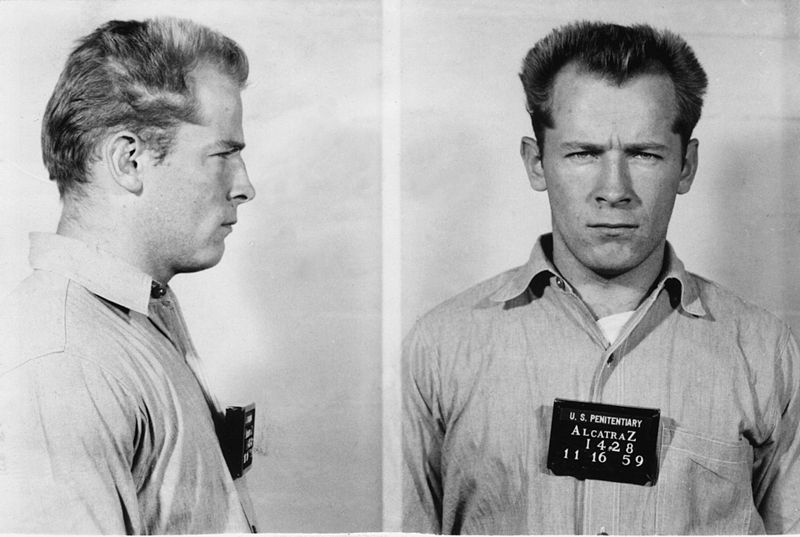

Mugshot for American organized crime leader James “Whitey” Bulger. Criminal data like this could be subject to de-indexation under the RTBF ruling. Photo by Bureau of Prisons, released to public domain.

Interview with Félix Tréguer, researcher at EHESS and founding member of La Quadrature du Net, France.

Conversations among the Global Voices members and across the digital rights space inspired our community to ask our colleagues — Internet law experts around the globe — to comment on the ruling and describe what impact it has had on policy and political debate in their countries since it was issued. In this second installment in the series, we hear from French Internet law scholar Félix Tréguer.

Are you familiar with the EU case on the “right to be forgotten”?

Yes. In Europe, the EU Court of Justice “Costeja” ruling has stirred a very heated debate about privacy and free speech on the Internet.

But I must underline that the ruling itself is not literally about the right to be forgotten. More accurately, it is a ruling that recognizes a right to the de-indexation of links attached to a person's name in search engines, based on the 1995 EU law on the protection of personal data. This means that when a given item is de-indexed by Google in the search results to a query that includes a person's name, it remains accessible through the search engines as long as the search query does not include that name. So it is quite a far cry from an actual right to be forgotten.

That being said, the ruling of course raises important concerns about free speech online. Clearly, the Court's decision restricts the right to information for Internet users, and the right to freedom of expression of online publishers whose content will be harder to find once it is de-indexed from some search results.

To me, the worst aspect of the ruling is the fact that, while it recognizes that the right to de-indexation is not absolute, it is the responsibility of search engines to make a judgment about whether a person's request for de-indexation of online content is valid. The Court noted that the search engine's decision on the request would depend on the “role played [by the claimant] in public life”. Accordingly, the threshold for de-indexing content is higher for a public figure than for the average citizen.So the ruling effectively gives Google the task of drawing the boundaries of whom and what belongs to the public sphere. By doing so, it is reinforcing the dangerous trend toward privatized online censorship – a trend we've gotten used to in the context of copyright enforcement.

It is truly disconcerting to see Europe's highest court issuing such an important ruling while being blind to the wider legal and regulatory ecology surrounding fundamental rights on the Internet.

Has there been local discussion and debate on the implementation of RTBF? Have their been local court cases?

Yes, besides the ECJ ruling, there have been court cases across Europe regarding the right to be forgotten.

Last January in France, a Parisian art dealer with a criminal record demanded the de-indexation of links to content related to a past conviction. A lower court decided in his favor, ruling that the complainant had a right to protect his reputation under France's law on personal data.

In 2012, a former porn actress also won a case on the grounds of local privacy laws after Google denied her requests to de-index links to her pornographic videos.

But besides these judicial decisions, there is an even more problematic side to the “right to be forgotten” debate in Europe. Right after the ECJ ruling, in May, the president of the French Data Protection Authority (DPA), who is currently coordinating the works of all European DPAs on the matter, announced in an interview that a third of the complaints received by her services (about 2000 out of approximately 6000 a year) were related to online content. Shockingly, she made clear that in those cases, the DPA does not just ask search engines to de-index specific content and links in search results, but that it goes straight to publishers (online media editors, bloggers, etc) to request that online information pertaining to any given complainant be removed or anonymized.

The prototypical case for the DPA is as follows: a former union leader comes to the DPA requesting action on a decade-old video showing him in speaking vehemently against his company's CEO. The video now tops the search results associated with his name, and, as he explains in his request, prevents him from finding a job. What the DPA can do in such cases is ask the publisher of the video to delete the name of that person from the text associated with the video.

But what this also means is that without any court approval or even clear legal principles on how to balance privacy and free speech, with absolutely no transparency on how much and what content is being taken down, and without considering other ways of protecting that person from employment discrimination, administrative agencies are orchestrating the censorship of online material. And this can have a big impact on the democratic debate. To continue with the previous example, what if, five years from now, the former union leader enters the field of electoral politics? Shouldn't the electorate have a right to know about his previous political engagement?

Even before the ECJ ruling, the implementation of the right to be forgotten had already gotten out of control in Europe. There is hence an urgent need to create an appropriate framework for balancing the right to privacy and freedom of expression, since neither existing law nor the ECJ ruling provide the appropriate answers.

Do you anticipate any threat to the online public sphere once it is implemented?

In the aftermath of the ECJ ruling, we're witnessing very dangerous developments. Besides encouraging the trend toward privatized censorship, the decision is also giving way to a rule-making problem.

First, Google is acting as a de facto public body and putting together a consultation on how best to implement the right to be forgotten. Google has denounced the ECJ ruling but is forced to implement it, and they logically need to come up with guidelines considering that both the ruling itself and EU law are very vague. But I find it odd that instead of calling for a legislative debate on workable principles regarding the privacy/free speech balance, the company instead created an “expert committee” to issue these guidelines. Even though the committee includes very commendable people such as Frank La Rue (the outgoing UN special rapporteur for freedom of expression), this process further legitimizes a form of private rule-making for the regulation of fundamental rights on the Internet, and as such it just cannot lead to legitimate rules.

Then, there are the national Data Protection Authorities from each EU member states who, in part in response to Google's own committee, are also working on guidelines regarding the implementation of the ruling. They started the process in July by questioning search engines (Google has already issued its response; Bing, Yahoo and others should soon follow suit). But while they have more legitimacy in this position than Google does, DPAs are administrative agencies and lack the democratic legitimacy or accountability of actual lawmakers. Culturally, they are also heavily biased towards the protection of privacy. Google's response to the DPA inquiries explains that in evaluating the requests received so far and acting upon them, it is facing questions such as:

- What is the nature and delineation of a public figure’s right to privacy?

- How should we differentiate content that is in the public interest from content that is not?

- Does the public have a right to information about the nature, volume, and outcome of removal requests made to search engines?

- What is the public’s right to information when it comes to reviews of professional or consumer services? Or criminal histories?

- Should individuals be able to request removal of links to information published by a government?

- Do publishers of content have a right to information about requests to remove it from search?

(Excerpted from Google's response to question n° 25 of the WP29 questionnaire)

So absent clear legal principles, it's quite worrying to see DPAs making up rules and adjudicating these very difficult questions raised by the right to be forgotten.

How can policymakers strike a balance between individual right to be forgotten and free flow of information?

That is indeed the crucial question, but one that needs to be taken up by both lawmakers and citizens, not by private companies and administrative agencies.

The right to be forgotten has its roots in criminal law, and no doubt there are very legitimate cases in which the protection of privacy should prevail upon freedom of expression. Europe has traditionally been a defender of strong privacy rights, which is in part explained by its history – in particular the surveillance practiced by totalitarian regimes in the 20th century – and the subsequent fear of seeing computers being used to empower states and private companies to spy on people. The focus on privacy has made Europe the worldwide leader for the protection of personal data. Today – in the age of the Internet, and especially in these “post-Snowden times” – it is an important legacy to carry forward. These old principles must be adapted to the technical and social realities of the Internet, so that we can protect the privacy of Internet users in the face of the harmful practices of the advertising, insurance and banking industries, among others, but also against the stunning return of mass surveillance by state powers.

On the other hand, in Europe, freedom of expression has not enjoyed a similar level of concern or protection as privacy. So in this debate on the right to be forgotten, there is a risk that online free speech will be routinely undermined, especially given that the problems raised by the ECJ ruling echo wider issues surrounding online censorship.

Going forward, there is a premise that should be questioned, namely the idea that the rules on the protection of personal data can apply as such to speech that is part of the public sphere. From a legal perspective, it seems to be a dangerous overreach, since I don't think it was the intention of French lawmakers in 1978, when they adopted the first law on personal data (nicknamed the “Computing and Freedoms” law). Still today, before the ECJ ruling, case law was unsettled: Many judges felt that only press laws should be used to regulate the public sphere, and thus refused to apply data protection laws to restrict freedom of expression online.

In the aftermath of the ECJ ruling, but also in the face of the many threats looming on freedoms online, Europe needs a “Marco Civil” moment. We need to raise and answer big questions about fundamental rights on the Internet, and in particular on the right to freedom of expression and the right to privacy, how to protect them, when and how they can be limited and balanced, while paying the utmost attention to applicable international human rights law.

Ultimately, it should not be up to Google or other Internet companies to implement these rules. Nor should it be the responsibility of the Data Protection Authorities. It must fall to European lawmakers to issue these rules and, consistent with the rule of law, up to the judiciary to implement them. An option to avoid private censorship while making sure courts are not flooded with requests would be having a “mediation authority” representing all stakeholders, from the public and private sectors as well as from civil society. Such a mediation body could give legal advice to claimants and online actors so as to find a common ground based on what the statutes and case law say. But when no agreement can be reached, then the case would be referred to a judge.

Want to lend your ideas to the conversation? We invite experts and interested individuals to answer these questions for us — please feel encouraged to respond to this post in the comments section or to send your thoughts to us at advocacy [at] globalvoicesonline [dot] org. We look forward to publishing them and continuing the conversation.

2 comments

we don’t like privatised online censorship or private rule-making. We need an Internet Bill of Rights to balance the individual’s right to privacy and the public’s right to know and right to freedom of expression.