Memorial plaques are just one of the many things in Almaty that Keen has documented. Photo by Dennis Keen, used with permission.

Buy the Central Asia Lonely Planet guide book and turn to the section dealing with the Kazakh city of Almaty. The “to see list” probably doesn't include hand pumps, handpainted signs and heating stations. But then again, what is a city without these things?

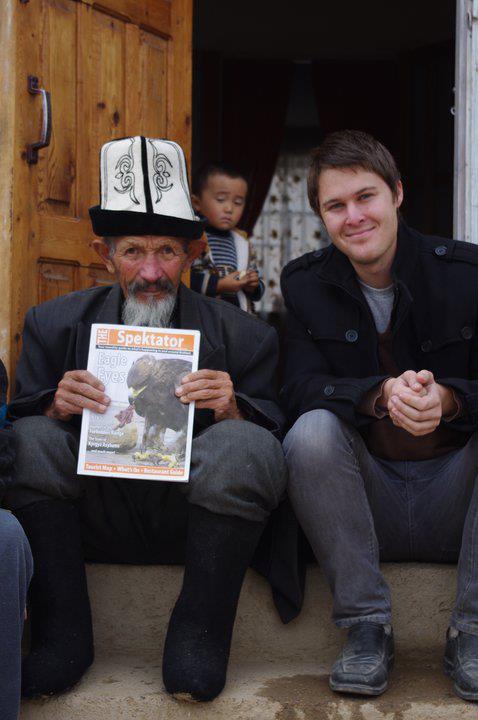

“Walking Almaty” is not Dennis Keen's point of entry into Central Asian blogging. That would be “KeenonKyrgyzstan“, perhaps the most entertaining English-language resource on traditional Kyrgyz culture ever produced. Between them came “EurasiaEurasia” and the “Central Asian Falconry Project“, the former a mix of history, cultural trivia and music in Central Asia, the latter a veritable archive of resources for anyone interested in big bird watching in the region.

But having traipsed across jailoos in Kyrgyzstan, reflected on the Western world's fawning over female eagle huntress in Kazakhstan and Mongolia, and mused on the reggaefication of the Kazakh dombra — a traditional lute-like instrument — we now find Keen in more urban settings. If you thought you could never get excited about bus stops and dead stairwells in the former Soviet Union, have a read: Keen makes the banal beautiful.

Sary the eagle hunter was a regular and compelling feature in “KeenonKyrgyzstan”. Photo taken from the blog, used with permission.

Almaty, home to roughly 1.5 million people, is Kazakhstan's biggest city and one that is rapidly changing. Every day Dubai-style skyscrapers are thrown up on the back of the republic's burgeoning natural resource wealth. Some neighbourhoods are undergoing aggressive gentrification while others are being forgotten about completely. Giant, sprawling bazaars are under threat amid the rise of mall culture.

As the new Almaty makes itself known, the older version is in desperate need of someone to catalogue it before it disappears from sight. With a big camera and a gift for prose, Keen is just the person.

Many of the sojourns the blog describes are off the beaten track. Take Keen's recent walk in the Almaty neighborhood Tatarka, for instance:

One of Almaty's oldest neighborhoods is Tatarka, which means “Tatar woman.” Wait, that didn't make things any clearer? If you're an American reader, you might not know that Tatars are Turkic Muslims who live mostly in Russia. Don't worry, I'm sure they'll forgive you. Tatars used to live mostly in this hilly corner of town northeast of the center, and by some accounts they still do. These days, Tatarka is remarkable for being one of the few parts of Almaty that actually carries a neighborhood name, and one that is known by most.

The houses here are rich in wooden plats, carved eaves, and intricate windowframes. There are a lot of improvised trash cans, too, perhaps because the hilly terrain kept the roads here off of regular collection routes. I was twenty minutes walking from the center districts, but it felt like a faraway village. When I picked up a small bottle of Russian-style lemonade in a convenience store, the owner's lack of pretension certainly seemed characteristic of such a little town. “We just got those in today!” he said, and as things tend to do here, conversation soon verged from lemonade to the fall of the American empire. “If you're looking for a sparring partner”, I warned him, “you're talking to the wrong guy. I'm a migrant to Kazakhstan with a thing for Russian soda.”

While Keen's appreciation of carved eaves is a recurring theme of Walking Almaty, he is scathing about other features of the city-scape. Here he launches a broadside against aluminum facades:

The most unfortunate Kazakh design trend of the last ten years has to be the iodized aluminum facade. The metal panels [металлокассеты; metallokassety] are supposed to look futuristic, covering up aging concrete surfaces with a 21st century composite material. In practice, they warp, stain, and look smudged.

Other everyday objects that come under the scrutiny of Walking Almaty are neither beautiful, nor vulgar, but still tell a story:

Like paving tiles, manhole covers are a perfect illustration of disregarded infrastructure; they are literally right under our feet yet we pay them no attention. Yet if other pedestrians are anything like me, there have plenty of attentional surplus to burn. How about instead of checking out girls or fondly remembering your lunch, you train your eyes on the ground and make some mental notes? You might see a cast-iron disc, stamped with a bygone year, or molded in a beautiful pattern, or marked with a mysterious code. The power of observation can open entire worlds you never knew were there.

Visitors to Walking Almaty are able to retrace the urban walks Keen describes with the app mapmywalk.

Below are a selection of photos from the blog:

Communist-era mosaics are still everywhere in Almaty and other post-Soviet cities. Photo by Dennis Keen, used with permission.

Doorbells on houses in Almaty are sheltered from the elements by cut-off plastic bottles. Photo by Dennis Keen, used with permission.

Shoe repair shops are familiar to anyone who has travelled through post-Soviet Central Asia. Photo by Dennis Keen, used with permission.

Josef Stalin's taste for architecture was better than that of his successors. Photo by Dennis Keen, used with permission.

A house in Kökzhiek, an Almaty suburb. Photo by Dennis Keen, used with permission.

Smashed blue ceramic adds color to a wait for the bus. Photo by Dennis Keen, used with permission.

Central Asian cemetries are aesthetically impressive by day, eery by night. Photo by Dennis Keen, used with permission.

2 comments