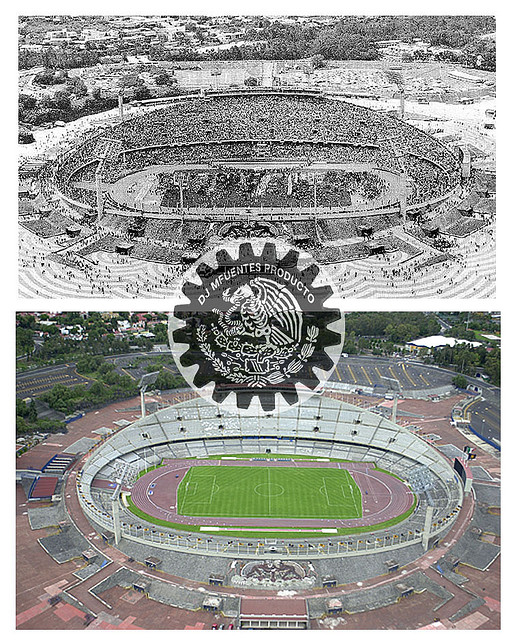

The Olympic Stadium in Mexico City, where the World Cup was held in 1970 and 1986. Photograph by Flickr user djmfuentes [1] (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Wherever the World Cup has traveled in Latin America, various kinds of social unrest has followed. This article is the second installment in a series that studies at the relationship [2] between the world's largest football contest and political turmoil. You can read the first part here [2].

Mexico 1986

The blog El Universal [3] looks at how crowds heckled [4] the country's then-president, Miguel de la Madrid, [5] during the opening ceremony of the 1986 [6] World Cup. More than 90,000 spectators shouted over the president's speech, infuriated that the country went ahead with hosting the games, just eight months after a major earthquake [7] hit Mexico City on September 19, 1985.

Mexico took responsibility for organizing the 1986 World Cup after Colombia lost the opportunity to host in 1982, after FIFA determined that Columbia did not meet the tournament's host requirements. At the time, Rafael Castillo, then president of the Mexican Futbol Federation, argued that the country's stadiums “only need a bucket of paint and a brush” and they'd be ready for fans and players, as the infrastructure was only 16-years-old (built for Mexico's 1970 World Cup).

Chile 1962

In 1956, FIFA held a summit to determine the 1962 World Cup's host country. In a brilliant speech, Chile's sports director, Carlos Dittborn, won his country the honor. “Because we have nothing, Dittborn promised, “we want to do everything.”

Just as in Mexico more than 20 years later, however, a devastating earthquake [8] hit Chile two years before its World Cup. Italian journalists Antonio Ghirelli and Corrado Pizzinibelli, writing for the newspaper “Il Resti del Carlino [9],” said of Chile's travails:

[Chile] es el símbolo triste de uno de los países subdesarrollados del mundo y afligido por todos los males posibles: desnutrición, prostitución, analfabetismo, alcoholismo, miseria… Bajo estos aspectos Chile es terrible y Santiago su más doliente expresión, tan doliente que pierde en ello sus características de ciudad anónima.

[Chile] is a sad example of one of the world's underdeveloped countries afflicted by everything that can go wrong: malnutrition, prostitution, illiteracy, alcoholism, misery… Considering these aspects, Chile is in a terrible state and Santiago is suffering the most of all, so much that it lost it's the characteristics of a city.

Ghirelli and Pizzinibelli left Chile before the World Cup even began, fearing for their own safety. Indeed, a few days before the opening match, an Argentinian journalist, mistaken for an Italian, was beaten up in a bar in Santiago.

Uruguay 1930

History's first World Cup took place in an era with no shortage of political and social trauma. In 1930, the tournament was sent to Uruguay, to take the game far away from Europe, which was still dealing with the fallout of World War I. When the U.S. stock market crashed in 1929, European countries suddenly worried that transportation costs might make it too expensive to send their teams to the Western Hemisphere. The World Cup's “story [10]” began then, when Uruguay offer to pay the transportation fees of participating teams.

The blog del29alneobatillismo [11] argues that Uruguay's organization of the soccer championship destabilized the country's social environment by declining commercial activity and leading to currency devaluation, unemployment, and a drop in wages. These World-Cup-created problems exacerbated an internal political crisis, precipitating a coup d'état [12] three years after the tournament.

Given the high economic demands placed on World Cup host countries, Latin America has not always been the most suitable place to hold the event. Of course, for all their social unrest, the Latin American people have been some of the World Cup's most hospitable hosts. True fans of football, it is the allocation of scare resources to a nonessential game that disturbs the public.

FIFA, for its part, recently determined that countries with large disruptive social movements and high levels of inequality should not host the tournament. Sports journalist Francisco Sagredo (@panchosagredo [13]) reiterated this in the magazine article in Qué pasa:

Tras #Brasil2014 [14], la FIFA evitará países con movimientos sociales y altos niveles de desigualdad. Por @panchosagredo [13] http://t.co/hw1MM6MYUO [15]

— Revista Qué Pasa (@revistaQP) July 18, 2014 [16]

After #Brasil2014 [14], Fifa will avoid countries experiencing various social movements and high levels of inequality.

This spurred questions and reactions on Twitter. From La Serena, in northern Chile, Roberto Peralta tweeted:

@revistaQP [17] @panchosagredo [13] / Entonces no habrá más mundiales. Ni menos en Sudamérica.

— Roberto Peralta (@cahuescar) July 18, 2014 [18]

So, there won't be any more World Cups. Let alone in South America.

Típico Chileno argued that countries without social movements don't even exist.

@revistaQP [17] @panchosagredo [13] todos los países tienen movimientos sociales… Russia no?

— Típico chileno (@juancarlostopo) July 18, 2014 [19]

All countries experience social movements… What about Russia?

Even so, according to Sagredo, FIFA believes that Russia and Qatar, the Cup's next two hosts, do not present any serious problems. Whatever one thinks about the modern state of social movements and inequality, however, everyone can benefit from studying the long history of hosting the World Cup in struggling societies battling troubling times. The lessons of Latin America are a good place to begin.