The Israeli army attacked and occupied the village of Khuza'a, east of Khan Younis in southern Gaza, in the week beginning July 21. It is still not clear how many Palestinians were killed or wounded, as for many days ambulances were prevented from entering the village and bodies were left in the street or under the rubble of houses.

Student Mahmoud Ismail survived the attack, and tweeted about his experience. Now he has now published a fuller account on Facebook.

About 1,100 people have been killed in Gaza and thousands more injured since Israel launched an operation there nearly three weeks ago. As civilian death tolls mount, Israel’s military says it is warning Gazans living in targeted areas to leave, but Palestinians have nowhere to go. The narrow 40-kilometre-long coastal strip is surrounded by fences and concrete walls along its north and east with Israel and on its southern border with Egypt.

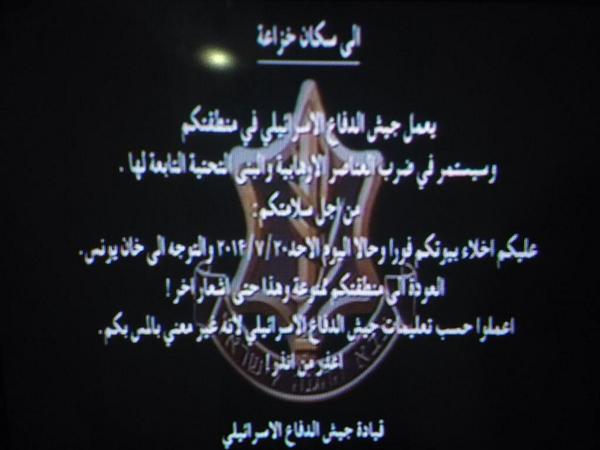

On July 20, the Israeli army called most of the residents of Khuza'a and sent text messages, instructing them to leave the village. They also intercepted Al Aqsa television channel, showing an evacuation warning.

Of the 10,000 residents of Khuza'a, approximately 7,000 left. Ismail explained why some people stayed:

كنّا ثلاثة آلاف شخص قرّر كل واحد فينا، وبشكل فردي، تجاهل كل التهديدات وأوامر الإخلاء والبقاء في بيوتنا. ليس في ذلك أي بطولة. كل ما في الأمر أن فينا من كان يمكن أن يصاب بانهيار عصبيّ لو نام في غير سريره، وآخر كان أكثر كسلاً ممّا تتطلبه عملية الإخلاء. وآخرين، مثلي، لم يرون في اسوأ خيالاتهم السيناريو الذي كان يترصّدهم بعد ساعات قليلة.

There were 3,000 of us who had each, on our own, decided to ignore all the threats and orders to evacuate, and to stay in our homes. There was no heroism involved in this; some of us would have suffered a nervous breakdown if we’d had to leave, and some simply didn’t have the energy required to get out. Others, like me, couldn’t imagine even in their worst nightmares the scenario that would play out in a few hours.

Khuza’a is close to the Israeli border. It was heavily attacked by Israeli forces during Operation Cast Lead in 2009, and the Goldstone Report later documented that Israeli snipers had shot civilians and ambulances were prevented from taking the wounded away.

During the latest attack, the Israeli army have once again prevented ambulances from entering the village and have targeted civilians, according to Gaza NGO the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights. Various eyewitnesses report that the army used Palestinians as human shields.

Ismail described what happened when the attack started:

الغارة الأولى قطعت الطريق التي توصل خزاعة بخانيونس. الثانية ضربت محولات الكهرباء. الثالثة أبراج شركة المحمول. الرابعة خطوط الهاتف الأرضي. نحن وحدنا وليل خزاعة حالك والقصف لا يتوقف. الطيران يعضّ كل شيء. زجاج الشبابيك يتساقط. الشظايا تغزّ بيتك وكل ما هو حولك. تحتمي في مكان تعتقد أنه أقل خطورة وتأخذ وضعيّة تعتقد أنها ستحميك. تحصي الغارات والاحتمالات: هل هذا الصوت لصاروخ في طريقه لنا؟ هل هذه القذيفة في البيت؟ لماذا لم تنفجر؟ هل استهدفت بيت فلان؟ المسجد الفلاني؟ هذه غارة إف 16، هذا قصف مدفعي. ليلة كاملة تحاول أن تحافظ فيها على عقلك وتمالك ما تبقى من أعصابك.

في الصباح قالوا اخرجوا. الصليب الأحمر على مدخل البلدة سيؤمن خروجكم، اخرجوا، الجيش لا يريد إلحاق الأذية بكم، العملية تستهدف بيوتكم وشوارعكم وأراضيكم وكل نواحي حياتكم، لكن حياتكم ليست هدفًا. خرجنا مع الثلاثة آلاف. مشينا في حشدٍ مهيب كما مشى سكان الشجاعيّة قبل أيام وكما مشى أجدادنا قبل 66 عامًا. نمشي، وعيوننا تفحص داهشة حجم الدمار الذي يمكن لقصف ليلة واحدة أن يتسبب به، نمشي كأننا نودّع كل ما تبقى. لكن هذا كلّه لا يهمّ، تجمّد مشاعرك وتركّز على قدميك. تصل إلى حيث قالوا. تجد رصًا من الدبابات ولا شيء آخر. لا تكاد تشعر بالفخ قبل أن يدوّي الرصاص في كل مكان.

ثم ماذا؟ ثم ضربٌ وصراخ ولغوٌ وجدل.

The first attack was on the road to Khan Younis, cutting Khuza’a off. The second hit the power transformers. The third, the mobile phone towers. The fourth, the landlines. We were alone, and the night in Khuza’a was pitch black, and the bombardment wasn’t stopping. The planes were hitting everything. The glass was falling from the windows, shrapnel was flying into the house and all around us. We sheltered in a place we thought was less dangerous, taking a position we thought would protect us. We counted the attacks and calculated the possibilities: is this the sound of a missile on its way to us? Is this shell in the house? Why hasn’t it exploded? Is so-and-so’s house targeted? Such-and-such mosque? This is a F16 attack, that is an artillery bombardment. The whole night was spent trying to hold on to our minds and what remained of our nerves.

In the morning they told us to get out, that the Red Cross at the entrance of the village would ensure our exit. Get out, the army doesn’t want to hurt you; the operation is targeting your houses and streets and land and every aspect of your life, but your lives themselves are not the target. Three thousand of us came out. We walked in a crowd as massive as the one in Shuja’iya days earlier, like the one our forefathers walked in 66 years earlier. As we walked, we saw with astonishment the scale of the destruction of a single night. We walked as if we were saying goodbye to what was left. But that wasn’t important; you had to freeze your feelings and focus on your feet.

We reached the point they had told us to go to, and found a line of tanks, and nothing else. We had just realised it was a trap when shots started ringing everywhere.

Then what? Then people being hit, screams, utter chaos.

Ismail, his mother and brother took refuge in a nearby house:

كنّا ثلاثة آلاف، صرنا خمسون شخصًا. تجمّعنا في بيتٍ واحد. نصفنا ليس من أهل البيت لكن هذا أيضًا لا يهمّ. توزعنا بين ثلاث غرف كي لا نموت معًا إن حانت اللحظة. (نعم، يراوغ الانسان عقله في لحظات كهذه ويقنعه أن حائطًا قديمًا يفصل بين غرفتين يمكن أن يحدّ من الخسائر التي سيتسبب بها صاروخ أطول من أطولنا وأثقل منّا مجتمعين).

في الغرفة معي كان عجوزان يهيّجان أزمتي النفسية: أحدهما بمفاضلته بين الحروب التي عاصرها في حياته والآخر بإلحاحه المستمر على شربة ماء قبل آذان الصيام متناسيًا للمرة الألف أن قطرة ماء واحدة لم تتبقى في البيت بعد استهداف الجيش لخزّانات المياه. الأطفال يمارسون دورهم الطبيعي في الحياة: البكاء خوفًا، البكاء مللاً، البكاء عطشًا. المهم أن يبكوا. الآخرين، وأنا منهم، نستمع إلى نثار حديث العجوزين بصمت وملل ونطالع الشبّاك والساعة في انتظار الصباح. (ثمّة، على ما يبدو، خرافة لا أدري مصدرها تقول أن احتمالات الموت تتضاءل وأن القصف تقل وتيرته مع أول خيط للضوء. لكنها، كما كل الخرافات، غير ملزمة بتوقعاتك منها وباسقاطاتك عليها).

We had been 3,000; now we were 50 people. We gathered in one house. Half of us were not from the family of the house, but that didn’t matter. We were distributed between three rooms, so that we wouldn’t die all together if the moment came. (Yes, people take leave of their senses at times like this, and convince themselves that the old wall separating two rooms could limit the losses caused by a missile taller than any of them and heavier than all of them put together.)

In our room were two elderly men who were making me feel even more anxious, one by comparing the situation with the other wars he had experienced, and the other by his insistence on drinking water before the call to prayer, ignoring the fact that barely any water was left in the house after the army had targeted the water tanks. Children were playing their natural role: crying from fear, crying from boredom, crying from thirst. The main thing is that they were crying. Others, myself included, were listening to the fragments of chatter of the old men in silence and boredom, and looked out of the window and at the clock, waiting for morning. (There seems to be a myth, the origin of which I don’t know, that says the probability of dying diminishes and bombardment decreases with first light. But as with all myths, your expectations will fall short.)

Ismail recounted having to watch a 20-year-old man dying over a period of hours, as no one was able to go and help him. Two of his own cousins died, one trying to help the other.

طلع الضوء وسقط الصاروخ الأول على درج البيت. اسوأ من صوت الإنفجار؟ صمت ما بعد الانفجار. أو ما تخونك أذنيك به فتظنه صمتًا. تشظّى كل شيء. اللون الرمادي هو كل ما تراه. لحظات ليعود لك سمعك وينقشع الغبار. الخوف يتحوّل إلى جثث واللون الأحمر يفضّ الرمادي. أمّك وأخوك؟ لا زالوا أحياء. تعود لقدميك، بعد ستة عشر ساعة خمول، وظيفتهما الأولى: الركض. تبتعد عن المكان، يسقط الصاروخ الثاني. تصفّر شظاياه في أذنيك، تتأكد أنك بخير. تهرب إلى بيتك، دقائق ويقصف بيتك. تهرب مجددًا. الكثير من الناس تتحرّك في الكثير من الاتجاهات. ترسم المروحيّة في السماء لك بطلقاتها طريق المنفذ الوحيد. تركض إليه. تركض كأن حياتك تعتمد على ذلك، لأن حياتك بالفعل تعتمد على ذلك. تركض فوق الذين سقطوا، تركض بجانب الجثث، عينٌ على الدمار والطريق المفخّخة بالحفر وعين على عائلتك التي تذوب في السيل الجاري.

Light appeared and the first missile landed on the steps of the house. What’s worse than the sound of an explosion? The silence of an explosion. Or what deceives your ears by making you think it is silence. Everything disintegrates. You can only see grey. It takes some moments for your hearing to return and for the dust to settle. Fear turns into corpses, and red breaks up the grey. Your mother and brother? They’re still alive. You get back on your feet, which have been idle for sixteen hours, and their first task is to run. You get away from the place just before the second missile hits. Shrapnel is whistling past your ears, and you check that you’re OK. You escape to your house, and minutes later your house is hit. You escape again. There are many people running in many directions. With its firing, the helicopter in the sky outlines the only escape route. You run towards it. You run as if your life depends on it, because your life does indeed depend on it. You run over the top of those who have fallen, you run next to corpses, with an eye on the destruction and the bombed road full of holes, and an eye on your family who are dissolving in the movement of people.

Ismail didn't know exactly what happened to the other people in the house he had been sheltering in — just that his shoes were soaked in their blood. After running from that house, he and family made it to their home, which was hit by three missiles minutes later. He was slightly injured.

He, his mother and brother then tried to leave the village. Helicopters were firing on people, and on the way he saw the bodies of his uncle and cousin next to their house. Israeli snipers were targeting people's legs to stop them leaving.

خرجت وعائلتي والكثير من العائلات من خزاعة. كيف؟ حالفنا الحظ. لماذا؟ لا أملك أدنى فكرة. الأهم أن ثمة من بقيوا هناك، وأن الجثث لا زالت حتى هذه اللحظة في الشوارع وتحت الأنقاض. كم عددهم؟ قد يكون 20، 50، 100.. لا أحد يعرف بشكل أكيد، وهذا هو الأمر الوحيد الأكيد. الصور الوحيدة التي خرجت من خزاعة حتى اللحظة كانت مقتضبة ومصدرها الجيش الإسرائيلي وتظهر مشاهد دمار تحشي الصدر بالحقد وتدمي القلب وتنبئ بأن الأيام الهادئة لهذه القرية الوادعة ولأهلها الطيّبين لن تعود عمّا قريب.. وربما للأبد.

My family and I, and other families, managed to get out of Khuza’a. How? We were lucky. Why? I don’t have the slightest idea. More importantly, the bodies of those who stayed are until now in the streets and under the rubble. How many were there? Perhaps 20, 50, 100? No one is certain. The few images that have come out of Khuza'a until now are from the Israeli army, and show heartrending scenes of destruction that fill your chest with hatred, and make you think that the tranquillity of this village and its people will not return any time soon – or perhaps ever.