Street Philosophy at City Bowl, Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa, by Anne Fröhlich on Flickr – CC license-NC-2.0

En archéologue des idées, Séverine Kodjo-Grandvaux explore les strates d'une épistémologie qui, au cours du dernier siècle, s'est construite essentiellement en réaction à l'Occident. D'abord sous le joug de son influence impérialiste, puis en réaction contre cette emprise [..] avec le mouvement des Indépendances et l'injonction à la décolonisation des esprits, vient le temps d'une pensée cherchant à se replier sur « l'identité africaine », contre le moule occidental. Un « retour au sources » risqué : « Dès lors que la philosophie cherche à se penser de manière « nationalitaire », c'est-à-dire continentale, nationale, ethnique, elle doit éviter plusieurs écueils, notamment celui de l'esprit collectif et celui de la particularisation excessive », écrit l'auteur. L'apport de la philosophie occidentale comme celui des autres courants de pensée ne doit pas être rejeté.

In her role as an archaeologist of ideas, Séverine Kodjo-Grandvaux explores the layers of a discipline which was built mainly in response to the West during the past century. During the colonial period, it moved along under the overarching control of its imperialist colonizers, then it evolved as a counter-reaction against the colonizers’ influence […] As the Independence movement swept throughout the continent (in the 50's), the philosophy of trying to return to “the African identity” and move away from the Western mold grew stronger. Kodjo-Grandvaux argues that such a “return to the origins” ideology is a risky proposition. She writes: “As philosophy is trying to fit into a “regional “pattern, [i.e, continental, national or ethnic], it must avoid several pitfalls, including the pitfall of homogeneous thinking and excessive isolation”. The contribution of Western philosophy as well as that of other currents of thought should not be dismissed.

Kodjo-Grandvaux highlights a debate about ethnophilosophy that African philosophers have been grappling with for a long time: the idea that a particular culture or region has specific philosophy that is fundamentally different from the other philosophical trends is controversial in itself. However, many modern African philosophers argue that their work is a critical reflection on African leaderships and how it impacts their compatriots daily lives. As a result, it is paramount that African philosophy develops in the context of the African continent and communicates to an African audience.

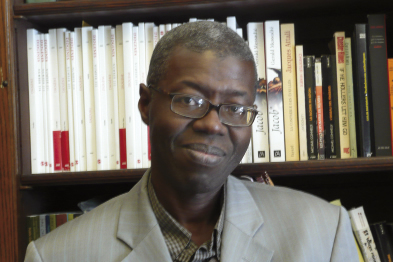

2. Souleymane Bachir Diagne (Senegal)

Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Senegalese philosopher and pionner of the new African philosophy scence – Public Domain

Souleymane Bachir Diagne, a Senegalese philosopher and professor at Columbia University, believes that African philosophers must make their work more accessible to their compatriots. He opines:

Nous devons produire nous-mêmes des textes en langues africaines et un de mes anciens élèves américain travaille en ce sens à une anthologie de textes de philosophes africains auxquels il a demandé d’écrire des articles dans leur propre langue. Des locuteurs de cette langue sont ensuite chargés de les traduire en anglais.

We need to produce our own texts in African languages and one of my former American students is working towards making an anthology of texts written by African philosophers who were asked to write articles in their own language. Then, native speakers will translate them to English.

3. Léonce Ndikumana (Burundi)

In addition to the importance of addressing their African constituents better, there are other trending ideas that are coming forth today from African philosophers. Léonce Ndikumana grew up in Burundi and is now a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. In his book, “Africa's Odious Debt: How Foreign Loans and Capital Flight Bled a Continent“, Ndikumana strives to combat many of the common narratives about Africa that are held as facts worldwide, such as the thinking that foreign aid subsidizes the African continent. In fact, capital flights from the African continent (1.44 trillion disappears without a trace from African countries, ending up in tax havens or rich countries) largely exceeds that of foreign aid (50 billion to Africa).

Ndikumana is also one of they key opinion leaders in Africa pushing back against international agency guidelines that often go against the will of African citizens.

4. Kwasi Wiredu (Ghana)

Countering false narratives is a growing trend among African intellectuals. Kwasi Wiredu, a Ghanaian philosopher, is one of those trying to do just that. He argues that a multiparty political system, often regarded as the base of democracy, is not always conducive to unity and stability. Instead, a democracy of consensus is a better suited to the African context:

Given that democracy is government by consent, the question is whether a less adversarial system than the party system, which is bound up with majoritarian decision-making, cannot be devised. It is an important fact that reasonable human beings can come to an agreement about what is to be done by virtue of compromise without agreeing on issues of truth or morality.

5. Kwame Anthony Appiah (Ghana)

However, another Ghanaian philosopher, Kwame Anthony Appiah, who currently teaches at New York University, is bucking the trend of Afrocentrism from African philosophers. He argues that Afrocentrism is an outdated concept. He believes one should encourage more trans-cultural conversation and less “regionalism”:

[Ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes] rejected the conventional view that every civilized person belonged to a community among communities […] A global community of cosmopolitans will want to learn about other ways of life on radio, on television shows, through anthropology and history, through novels movies, news stories and newspapers, and on the Web.