[1]

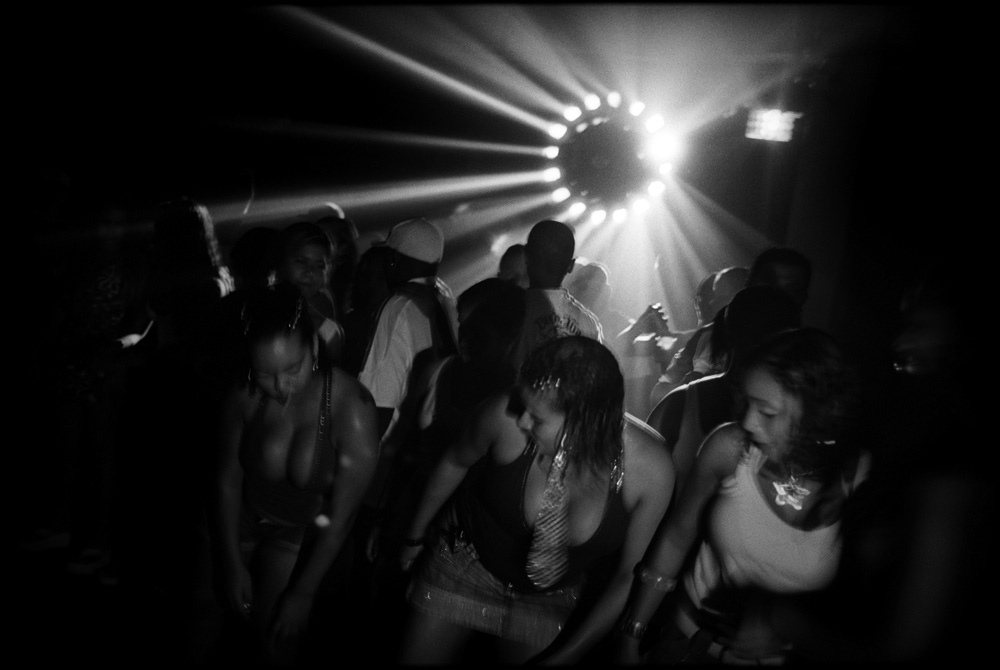

[1]Girls dance at a baile funk party in Rocinha, the largest favela in Rio de Janeiro. Photo by Flickr user Balazs Gardi NC-CC-ND 2.0

Leading up to the World Cup in Brazil, with sounds of gunfire in the background forbidden funk rappers continued to talk about what the government wants to hide: extreme violence, social segregation and racism in the favelas.

If you are in Brazil, you probably won’t get to hear the most explicit and iconic versions of these songs on the radio. This music genre is considered proibidão or extremely forbidden in the country and originated in Rio de Janeiro's iconic hillside slums or favelas.

Authorities say forbidden funk lyrics ‘glorify or praise drug violence [2] and criminal gangs’ in the favelas and say the songs help recruit people to gangs. Forbidden funk musicians disagree with authorities; they say their lyrics talk about their lives as it is the slums, in protest.

“If you are born inside a favela community, and you are there to tell what happens inside that community, you have to proudly assume you are telling what is going on inside that community,” said rapper MC Frank in the documentary “Funk is culture – Music Politics in Rio de Janeiro [3].” Frank was arrested along with 5 other rappers in 2010.

Police have used two articles [4] within the ‘crimes against public peace’ law in the penal code to charge and jail rappers in the past. Article 286 ‘apology to crime or criminals’ and article 287 ‘public incitement to crime’, both carry fines and 3-6 month jail terms.

Besides the difficult relationship forbidden funk rappers have had with the law, bailes, which are large funk dance parties in the favelas, also have a long history or criminalization and decriminalization in Rio de Janeiro.

Finding forbidden funk in Brazil

The most explicit forbidden funk songs are hard to reach from outside the favela. But that doesn't mean they are not out available. Besides being on YouTube, some songs are tamed into “well-behaved versions” for mainstream audiences.

An edited version of a classic forbidden funk song Rap das Armas (Weapons’ Rap) was a part of the award-winning film Tropa de Elipe’s soundtrack. The sound of guns was deleted for the film’s version:

Here’s the ‘forbidden’ version:

The big 2010 crackdown

In November 2010 Rio’s military police raided the Alemão Complex, the single largest congregation space in the favelas and arrested MC Frank, MC Smith and three other funk singers, in one of the city’s biggest invasions in recent times.

This episode resulted in two documentaries and a big budget fiction film. The documentary Grosso Calibre [6] is the short version of the film Proibidão [7], rapper MC Smith is the main character in both. The recent released fiction movie Alemão also had rapper MC Smith's participation this time as an actor and consultant. Alemão [8] seeks to portray the November 2010 police invasion at Alemão complex.

About his arrest MC Smith says: “I was arrested for expressing my ideas”. He was kept in prison for 15 days and declared innocent. On the blog Funk Neurotico he talked about the episode [9]:

I have some thoughts on the situation I went through. You should not deal with evil by being evil. I could have become a criminal, but that didn't happen. While everybody else was calling me an outlaw, I was being a revolutionary. Nelson Mandela needed to stay in prison for 27 years to be recognized. If I lose my life doing what I do, that's fine. I don't plan on being a millionaire or being famous until I am 90 years old. I am here to make history, to become a lesson taught by teachers in schools. That is my plan. I want to leave a legacy.

Forbidden funk’s link to criminal factions

On the other hand, academic and activist Paul Sneed says forbidden funk has been used by the Comando Vermelho criminal faction to strengthen its hegemony in the favela. [10] According to him, members of this criminal faction sponsor bailes and uses them as a platform to stage their power. This specific crime faction, he says, also promote the production of clandestine rap songs such as “Bandido de Cristo”(Bandits of Christ) by recording live presentations and making bootleg CDs afterwards as a way to propagate their ideas.

Several criminal factions control numerous bailes because they happen in the favelas. But that doesn't mean bailes only play forbidden funk. There are all kinds of themes in funk lyrics and that includes forbidden funk songs, but not exclusively, even if the baile is financed by drug dealers.

Funk’s Brazilian beginnings

American funk started to become popular in Rio in the 1970s. It gradually developed into a distinctively Brazilian style, with lyrics in Portuguese called funk carioca. [11] Bailes or dance parties that played funk carioca were held across the city in the 80s. In 1992, a mass fight on Rio's Arpoador beach was blamed on funk fans and baile clubs were closed by authorities. The music soon moved into the favelas, away from police control, and here it evolved yet into funk proibidão or forbidden funk.

According to music researcher Palombini [12]on the website proibidao.org, in the 80s, a soul singer called Gerson King Combo recorded a single called Melô do Mão Branca interpreting a police officer on the phone saying:

Ratatá! Papá! Zim! Catchipum! são sons que você tem que acostumar, essa é a música que toca a orquestra do Mão Branca, botando os bandidos pra dançar

Ratatá! Pará Catchipum![as gun sounds], these are the sounds you will have to get used, this is the white hand's orchestra music making all gangster dance.

But it was only in 1995 that prohibited funk as genre started to show up, when MC Júnior and Leonardo together with Cidinho and Doca made the sound of machine guns, pistols rifles and grenades popular within their songs. All these rappers were called to court by that time.

The attempts of funk criminalization started with funk carioca in 1999 and continued with the forbidden version.

Rio laws criminalizing bailes

Specifically, there is a long history of laws prohibiting and protecting bailes in Rio de Janeiro. In 1999, a State Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry [13] was created with the intent of investigating baile funk which according to them increased violence, drugs and deviation of behavior in youth. From this investigation the first law [14] making the people who run the places where bailes were organized accountable was created in 2000. Four years later, a law [15] by congressman Alessandro Calazans canceled the law prohibiting baile-related activities, declaring baile funk a popular cultural activity.

Again in 2008, a new law [16]revoked the previous law and created stricter rules about bailes which now extend to raves, as well. Among the eight new restrictions was the requirement to hire a company authorized by the Federal Police to take responsibility for internal security of bailes and raves. In 2009, this law was also revoked and a new one, law 5543 [17] from congressman Marcelo Freixo and Paulo Melo was passed, which defines funk as a popular musical and cultural movement and declaring that all issues related to the subject should be dealt with by the state of the art. The law also prohibits discrimination and social [18], racial and cultural prejudice against funk.

So for now most bailes in Rio de Janeiro are safe from the law, but forbidden funk rappers continue to walk a thin line with the country’s crimes against public peace law, while making the music they believe in.

Emilio Domingos [19] and Sheila Holz [20] contributed to this report.