#SOSVenezuela graffiti on the highway and behind the National Bolivarian Guard Soldiers watching the demonstration below. Photo by Kira Kariakin.

This article by Kira Kariakin was originally published in the What's hot? section of the Future Challenges website. This post is part of our special coverage on Protests in Venezuela.

On February 12, 2014, Día de la Juventud (Youth Day,) the Federation of Universities’ Students decided to take a stand to demand more security from the government in a country-wide demonstration. The origin of the protest was one in San Cristóbal, Táchira, that occurred a week before after students saved a female classmate from attempted rape on the campus of Los Andes University. The authorities violently put a stop to this protest, causing students to unite on Día de la Juventud to stand up for their rights, continuing to demand more security. The demonstration on February 12 was strongly quelled causing three deaths and several injuries, and started an ongoing chain of demonstrations.

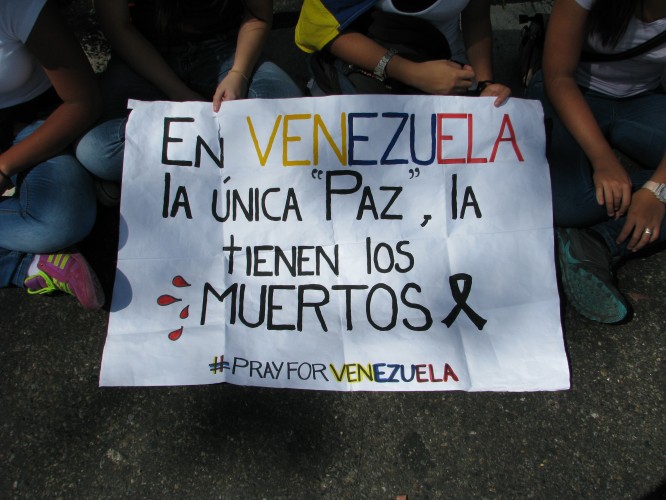

To this day (March 11,) the violence of the protests has claimed 21 lives, and led to 318 injured and the arrest of more than 1,000 people. The opposition and the students are accusing the security forces, the National Guard of the People, the National Bolivarian Police and the “colectivos”, of being responsible for these casualties. “Colectivos” are civilian (paramilitary) urban organizations that were supported and armed by the government of Hugo Chavez to defend his revolution. Colectivos like “La Piedrita” and “Los Tupamaros” have been photographed working with the special intelligence police, SEBIN, shooting, beating and intimidating protesters.

Demands

Students are now demanding a cessation of violent repression and especially respect for the human rights of detainees. Citizens that have been detained over the course of the protests are said to be brutally tortured (electric shocks, rape, beatings) and denied legal rights. They are demanding that detainees be cleared of all charges and released. Another plea is to end the censoring of information and the limiting of the free media. The protests have not been adequately reported by local television and radio stations because any station that broadcasts this kind of news may face severe legal consequences like fines and the revoking of their licenses. Accordingly, recorded incidences have been disseminated mostly through social media channels rather than through other sources due to the restrictions and ambiguity of the Ley Resorte. The government has failed to fully acknowledge, take responsibility for, or show any diligence to investigate these events. For the most part, NGOs and pro-human rights groups like Foro Penal Venezolano, Provea, Espacio Público have gathered documents and testimonies and presented them to the Ministry of Public Affairs, the “Defensoría del Pueblo” (a sort of Ombudsman,) and international bodies like the Organization of the Americas States.

En #SOSVenezuela, cuando el ciudadano común pide PAZ los militares de @NicolasMaduro lo apuntan con las armas pic.twitter.com/sXsqCQgsT5

— Noé Pernía (@noepernia) March 2, 2014

When the common citizens ask for PEACE, the military of Nicolás Maduro points at them with guns.

Responsibilities

From the government’s point of view, opposition leaders are responsible for the violence resulting from the protests, and students are merely useful fools that they are using to advance their agenda. This argument would be credible if the main opposition leader, Henrique Capriles (First Justice Party,) had not been against these protests foreseeing the possible consequences. The students were in fact supported by Leopoldo López (Popular Will Party,) and Representative María Corina Machado (Independent) who insisted that the demonstrations would be non-violent. While Capriles was preparing for a long-term goal to better connect to the needs and problems of the least-privileged, López and Machado wanted to show the discontentment among the youth and middle class through protests. This brought friction to the coalition of the opposition parties, MUD (Mesa de Unidad Democrática – Table of Democratic Unity.)

Machado and López’s support of the demonstrations allowed the government to accuse them of conspiring to perform a “fascist” coup d’état against President Nicolás Maduro, with the aid of the “empire” of the United States of America and the CIA, extending his accusations to CNN since it is a station that is actively covering the protests (video.)

On February 18, Leopoldo López surrendered to the authorities for charges of conspiracy, instigating rebellion and murder (the murder charge was withdrawn later on.) That day, the “guarimbas,” barricades on the streets, began throughout main Venezuelan cities. “Guarimbas” are not controlled by opposition leaders, and are also not supported by the general population. They are an expression of the more radical opposition that wants the government to fall. Some retired generals, like Ángel Vivas, have been supporting the “guarimbas” by giving them instructions regarding how to make “miguelitos” to damage the tires of motorcycles or putting wires across streets to injure passersby arguing that it is on self-defense among others reasons. These measures have claimed the lives of at least three civilians.

The students have remained largely independent from opposition leaders in regards to their actions and decisions. The effectiveness of the protests have been questioned by Chavistas because in Caracas, demonstrations have mostly broken out in only the eastern part of the city, but lately have started to happen on the west as well, like in Caricuao. Some analysts say that the absence of people on the streets in the west is not caused by lack of discontent but a fear of the retaliation of the “colectivos” in their controlled neighborhoods. However, in other major cities the protest have been all-encompassing. In San Cristóbal, for example, the protests have been particularly strong.

The government called for a peace conference extending an invitation to anyone who would like to participate, including students and leaders. Most opposition leaders refused to attend until the government put an end to repression, arrested students are liberated, and words like “fascists,” “murderers bourgeois,” “conspirators,” etc., are eliminated from the government’s rhetoric. Because there is no trust between the different stakeholders, the dialogue is at a standstill.

In the meantime, strong repression has not stopped, not even for the first anniversary of the death of Hugo Chávez on March 5th.

The role of social media

Venezuelans have actively blogged, tweeted, and posted testimonies, videos, and photographs on Facebook, Flickr, YouTube and other platforms. Due to media censorship, Twitter has become a dominant media outlet for Venezuela. Under the hashtags #SOSVenezuela, #PrayforVenezuela, #ResistenciaVzla among others, all the events have been documented and the news has spread far beyond Venezuela’s borders. Photos and videos that local media outlets cannot broadcast have been published by citizens and are available for the world.

In the days previous to the Oscars, a Twitter campaign was used to ask artists to publicly support the protestors in Venezuela with some success. Also heart-breaking declarations, personal statements and frustration have been vented using these hashtags.

“Somos demasiado jóvenes para ser tan infelices” #SOSVenezuela #PrayForVenezuela pic.twitter.com/lWDngdOnsJ

— Juan M. Fernandez (@Janman93) February 25, 2014

We are far too young to be this unhappy.

“@ElNacionalWeb: Manifestantes en Altamira honran a los venezolanos caídos en protestas estudiantiles pic.twitter.com/3g06Vct6gx” #SOSVenezuela

— Alejandro Rodriguez (@alejandrorf) March 3, 2014

Protestors in Altamira honor the Venezuelan students who fell in the protests.

Looking forward

After almost 30 days, it is still not clear if the demonstrations will fade. There are a lot of rumors and hypotheses as to what is actually happening within the government and in opposition groups and parties. In the government, the rumors are about clashes between two factions: the military represented by Diosdado Cabello, president of the National Assembly, and the civilian embodied by the President Nicolás Maduro.

On the side of the opposition, there are four conflicting fractions: the students’ movement which acts mostly independent from the political parties, the followers of Henrique Capriles with a moderate approach, the followers of Leopoldo López and María Corina Machado prone to stay on the streets, and the radicals, “guarimberos,” that are pursuing a quick fall of the government with a combination of civilian-military action.

The dynamics of all these sectors are now in play. The protest has taken its course and is out of the control and influence of the opposition leaders. Uncertainty and despair about the future are now combined with frustration and rage. It is difficult to foresee possible outcomes. The population is suffering under rampant crime, scarcity of products and human rights limitations, and is asking for help: #SOSVenezuela.

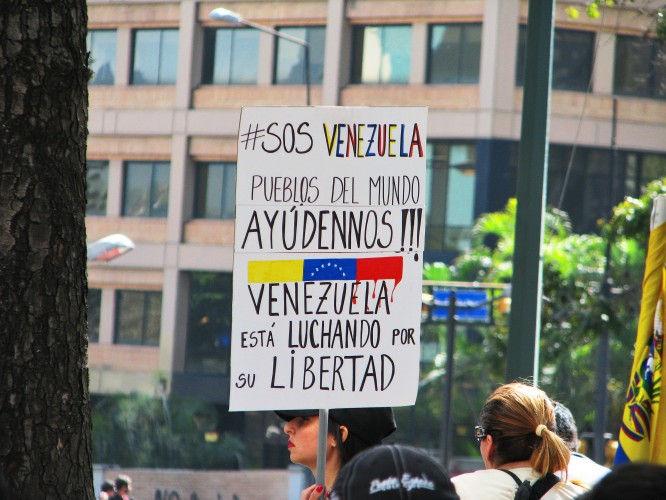

“People of the world, help us! Venezuela is fighting for its freedom” #SOSVenezuela. Photo by Kira Kariakin.

1 comment